Introduction

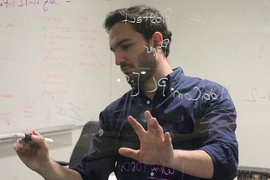

Fadel Adib is an associate professor at the MIT Media Lab and Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. His work pushes the limits of wireless sensing: to monitor climate change in the oceans; to impact food production, health, and space exploration; and to see through walls.

In this episode, MIT President Sally Kornbluth talks with Adib about his work and how he’s inspired to solve pressing global issues. Along the way, they discuss his belief in the importance of inspiring others and democratizing advanced tools and technologies, as well as his early life in Lebanon and his family-held belief that education has the power to change lives.

Links

Timestamps

Transcript

Sally Kornbluth: Hello, I'm Sally Kornbluth, president of MIT, and I'm thrilled to welcome you to this MIT community podcast, Curiosity Unbounded. In my first few months at MIT, I've been particularly inspired by talking with members of our faculty who recently earned tenure. Like their colleagues in every field here, they're pushing the boundaries of knowledge. Their passion and brilliance, their boundless curiosity, offer a wonderful glimpse of the future of MIT.

Today, my guest is Fadel Adib, associate professor in the MIT Media Lab and in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. As you'll hear, Fadel is passionate about creating wireless and sensor technologies that connect the world in new ways, with potentially powerful impact on a wide range of questions—from climate change to food security to space exploration. Fadel has an incredible journey that's taken him from Lebanon to MIT, where his work as a graduate student led to his first startup, and where he's now been an associate professor since 2017. Fadel, welcome to the podcast.

Fadel Adib: Thank you very much for having me.

Sally Kornbluth: I'm going to get started by having you briefly describe your work. But I know you've done many interviews before. This time, I wonder if you could describe it as if you were trying to inspire future scientists. Those young teenagers who are thinking about what they want to do, to get excited about what might be possible in the future.

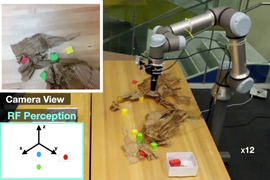

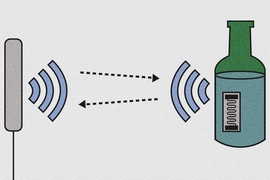

Fadel Adib: Absolutely. I like to start by asking them a question, which is, "What superpower do you want to have?" or "What superhero do you wish you could be?" For example, different people answer in different ways. If someone says, "I want to be like Superman because he can see through walls," then I answer, "Well, actually, we build this technology that can give you X-ray vision."

Sally Kornbluth: That's great.

Fadel Adib: On the other hand, many of the teenagers today are very societally-minded or climate-minded, so they might say, "My superpower is that I want to be able to solve climate change." If that is what they answer, then I tell them, "Well, we have a solution for that as well, because we're building these new technologies for the ocean that would allow you to address some of the biggest problems that are facing climate change."

The reason I like to ask these questions and answer them in this way is, this is also what inspired me personally in order to become a scientist. What I wanted to do is, I wanted to do things that are impossible. To make sci-fi a reality, but at the same time, to build new technologies that help us solve real-world problems. By asking these questions, I'm channeling my own motivation to them and pitching it in a way that I know that we can connect on, and showing them how science and technology is an amazing pathway to solve real-world problems.

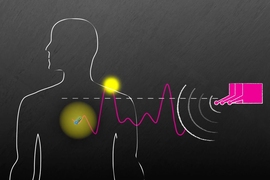

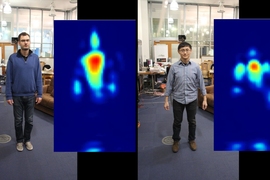

Sally Kornbluth: I love that because there's a lot of things that we see in the movies, we see on television, that are not yet quite reality, that people think are just part of the way things work. For example, you'll watch a law enforcement program as if they can see every motion of every individual inside a building. But from what I understand of your work, that is pretty close to reality.

Fadel Adib: That is true. But that's because the research that we've done at MIT made it close to reality. What's interesting is, when we started working on this research on seeing through walls, people were like, “Can you use infrared to see through walls?" The answer is like, "No, unless you're in a movie or in some cartoon."

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly.

Fadel Adib: In reality, you actually need to use radio signals, or RF signals, to see through walls because they can go through walls. Which is why, for example, you can get Wi-Fi from another room, but not infrared. But also what is interesting is that a lot of the research that we do sometimes is inspired by sci-fi.

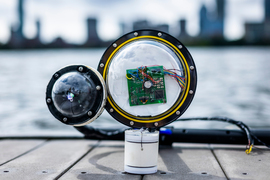

I remember once watching, I think maybe a James Bond movie. They showed that they can communicate from underwater to the air. I realized, "Wait, I know that is not something that is possible.” That led us to thinking about how we can build technologies that enable direct underwater to air communication, which has been an open problem for a long time.

Other times, there are documentaries, for example, Blue Planet. I was watching Blue Planet and I realized, "Oh my god, most of the ocean has not been explored and that's why scientists haven't discovered even most marine animals, and hence, most probably organisms that are on this planet. How can we build technologies to help in these discoveries?" What's fascinating is that science and technology inspires sci-fi, but in turn, that also re-inspires science and it keeps going in a nice reinforcing loop.

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly. I actually have a friend who's always posing these superpower questions, but he always puts practical constraints on them. In other words, like, "You could fly, but only at four miles an hour." It's a little different from science fiction. But I like the notion that when you come up with practical solutions, there will always be some constraints that you have to take into account.

What really surprised you about your work when you were first getting started? In other words, thinking back to as you first started to get things moving, did things proceed as you anticipated? What were the surprising things that came up or came around the corner?

Fadel Adib: As a scientist, we also operate between the technology and science and invention route. This is the type of work that I do. You're surprised when something works for the first time. I remember, for example, when we were doing the work on seeing through walls. The first time I got it to work, it was in lab after midnight. I was the only one who's running experiments. I was running an experiment with a robot on the other side of a door. And it worked. I remember emailing my advisor, I think at 12:30 AM, and I was like, "We can see through walls! Not exactly walls, and not exactly see, but we can track this Roomba that is moving on the other side of a door, but we've just discovered that we can do that."

I think there's also sometimes other things that happen almost by chance. I remember before one of the deadlines, we originally thought we could see people moving because of mobility, like you can detect them or track them because they are moving. We thought that we need to walk around. We had a paper deadline. I asked my collaborator at the time to stay still so that I can start the system and then so that I can start tracking him. I realized that even though I started the system, I could see him, I could locate him using our system. I was like, "Why am I able to locate you? There must be something wrong." As we dug deeper into it, I realized that he was appearing and disappearing, appearing and disappearing in these images that we were creating. I realized it's actually associated with his breathing.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, fantastic.

Fadel Adib: It turned out that by digging in and trying to understand what the problem is, we discovered you can actually not only detect people based on their breathing, but you can even monitor their breathing using wireless signals on the other side of the wall. That led us then afterwards we realized you can even detect their heartbeats using wireless signals. Sometimes you discover something and you're trying to understand why this is happening. Then we started looking into the medical literature, and we're not medical researchers, and we realized, actually, it's related to this concept called ballistocardiography. Which is that when your heart pumps blood, it creates a force that acts on different body parts and it causes them to vibrate. These vibrations are so tiny, but we had refined our hardware and algorithms to be able to detect them.

Sally Kornbluth: So you can actually detect anxiety through walls?

Fadel Adib: We actually demonstrated that you can discover human emotions by relying on wireless signals. Not all types of emotions, but at MIT, there's this new field that came out that is called affective computing which uses vital signs to discover human emotions. We created bridges between that and what we were doing. We showed that you can build a device to discover different human emotions. Interestingly, that became the plot of a whole episode of The Big Bang Theory, which is an American sitcom. Again, this goes back to how science inspires popular culture.

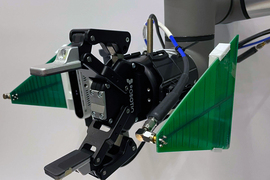

Sally Kornbluth: Yes, absolutely. You talked a little bit here about sensing human beings, extending that to physiological sensing. But your sensing work goes in many directions—oceans, healthcare, robots, sensing, and manipulation. Is there an area of your work where you think, at least in the short term, we might have the biggest impact?

Fadel Adib: On one hand, I would say our health work has already had impact because we started a company, it's deployed in thousands of homes and hospitals to monitor patients continuously, to help in discovering new diseases and so on.

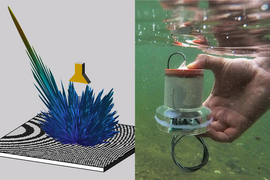

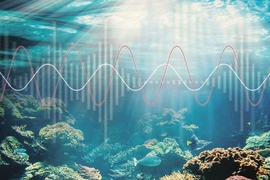

But currently what I'm very excited about is the work in the ocean because it can really transform so many things. More than 95% of the ocean has never been explored or observed. This has significant implications for climate change which is why, for example, we only hear about the big problems, like an iceberg broke off and left in the ocean. Why? Because it's very difficult for us to do long-term underwater observations. The reason is more than 95% of the ocean is hidden from us, so we don't know in what way climate change is impacting it.

There's other applications why enabling large-scale underwater sensing is important. For example, food production. According to the United Nations, the world's fastest-growing food sector is aquaculture, which is the production of seafood. Over there, it's very important to be able to monitor these aqua farms, protect them against environmental hazards, detect diseases early, and there's no easy solutions to do that today.

There is, of course, other applications in robotics, disaster response. One other area I'm super excited about is space exploration. NASA scientists, for example, discovered subsurface oceans in Saturn's moon, Enceladus, and Jupiter's moon, Europa. Over there, it's even more difficult to do sensing. We're starting to work with them on incorporating our technologies as part of future space missions so that we can search for alien life in extraterrestrial oceans. The reason why I love this is, it truly changes how we're going to be doing sensing and monitoring of the underwater world, on the one hand. There's amazing, elegant technology, but it could also have a lot of impact, from climate to food production to extraterrestrial exploration.

Sally Kornbluth: Back to the oceans a minute. Do you see this as part of early warning systems?

Fadel Adib: Absolutely, absolutely. It could be early warning systems for weather and disaster response. For example, with sea levels, you have a hurricane, but it could also be an early warning system for a harmful algae bloom that happens in an aqua farm which could wipe out tons of food, like an entire season. You want to create sustainable food sources and you want to create early warning systems for that so that you can safeguard them.

Sally Kornbluth: In the non-scientific realm, are any of your discoveries of utility, for instance, archeologists?

Fadel Adib: That's a very interesting question. The ocean stuff can have applications there, like underwater archeology is a big open problem. You can help search for things, understand what has been submersed over time. We have not explored that yet. Another area could be somehow related to archeology, but also, is when you have an earthquake and people are buried in the rubble. Being able to use wireless signals to detect life signs in a cheap and accessible way can help you save people's lives, but also it has applications maybe in some underground archeology.

Sally Kornbluth: I see. You can actually see first responders armed with mobile wireless devices and detectors.

Fadel Adib: They could even use the Wi-Fi that is already in their phone.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, wow.

Fadel Adib: Because that's what we showed. We showed that you could use Wi-Fi to do these types of detection.

Sally Kornbluth: That's amazing. Talk a little bit more about climate change, maybe, and how you see the applications. Because obviously that's an existential threat that we're trying to mobilize all corners of MIT and I know that's true of many other institutions to address in as expeditious a way as possible.

Fadel Adib: Yes. I will start with my journey with it. When I started as a faculty, I thought to myself, “What is an area that I can try to address, where it can have a big impact on the world and solve some of the world's biggest problems?” Of course, climate change has been around for a while, but I started around 2016 and around that time, clearly there's been even more momentum. Which is great, because it led me to think more about it. As I dug deeper into it, I realized that the part that plays the largest role in the world's climate is the ocean, and it is also the part of our world that has been most impacted by climate.

Now, my mind as a scientist and an engineer started thinking, “How much have we measured? What have we observed? What have we not observed? What are the big problems?” For example, there is many concerns of, the temperature rises by a certain amount, and the CO2 that is in the ocean suddenly gets released. This is not a linear effect. It's not like we're going to wait and suddenly we can backtrack. This is a big problem because it's not like you are gradually approaching a tipping point and then you reach it. No. What happens is you're gradually approaching and then you're going to accelerate and that becomes a big problem. I realize that we've measured so little. A lot of what scientists and climatologists and oceanographers are concerned about in the ocean are non-linear impact. For non-linear, you can't use what is called sparse sampling where you deploy samples.

Sally Kornbluth: Or historical data to extrapolate.

Fadel Adib: Or historical data. You need real-time measurements. You need them at high spatial-temporal resolutions. That led me to start thinking about how we can deploy sensors at scale. Deploying sensors at scale faces problems. Because how do you power them? How do you make them communicate? How do you collect the data from them? How do you use them for continuous monitoring? I realized there is no good solutions today. Now, I'm not coming from the background of an oceanographer. I'm coming from the background of using Wi-Fi to see through walls. Or even some of the healthcare applications. We started thinking about how you can build these sensors that use wireless signals of some form and allow them to work in the ocean. It was a learning curve but that's the beauty of being at a place like MIT. People embrace the fact that you're coming from one field and going into another field and creating bridges with this other field and trying to solve the problems. Because we're all in this together. We're all trying to solve the world's biggest problems.

Sally Kornbluth: Right. How you place something in the deep ocean and be able to generate continuous power, so you don't lose strength of signal over time, et cetera. But there are a lot of people around here working on power generation and long-term battery storage and everything else, so I'm sure there are many interested collaborators.

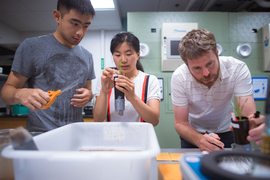

Fadel Adib: It ended up being a much more interesting problem even than we started. We started with the goal of deploying sensors at scale. Then we realized one of the biggest challenges is, how do you reduce the energy consumption of underwater communications? Turns out, that's an area that we know and we understand from the wireless networking world at IoT [Internet of Things] because you have to use the energy consumption of Internet of Things devices or wireless devices, so that people don't need to keep charging them the whole time. But also, then it turns out that there's problems in energy harvesting. How do you harvest energy? For example, we're starting to work with some collaborators on microbial fuel cells so that they can harvest energy from the ocean floor. It turns out there's problems in robotic navigation, and then it turns out there's problems of, how do you now build machine learning models that can fit on these tiny sensors that are very energy and compute constraints, so that you can do some inference locally and then only send the data that you need to send?

It ended up being a much richer problem space than when we went in and one that has potentially much more areas of impact. Of course, climate is how we started and it's one of the biggest drivers. But food security, which is also somehow related to climate, is also a big problem. There's the human desire of exploration and this allows us to touch as well.

Sally Kornbluth: I was actually surprised by your comment on the large, large, large fraction of the ocean that is unexplored. We think about there not being many places on earth that still have pioneer exploration potential. That's fascinating. The other thing is the notion of microbial fuel cells as a source of powering undersea exploration is really fascinating.

Fadel Adib: To be honest, we were thinking first of harvesting energy, for example, from sound underwater. Because sound travels over longer distances. That's how we were doing it. Or maybe even putting a small battery. But then researchers reached out to us and they were like, "We've been building these microbial fuel cells for a long time. Maybe we can combine efforts, but we're only able to generate maybe up to 1 or 10 milliwatts from them, and you cannot communicate with this." I told them, "We only need a few microwatts."

Sally Kornbluth: Yes, exactly. "So, we're good."

Fadel Adib: That's more than enough.

Sally Kornbluth: That's excellent. Let me turn this a little bit to some more personal comments. You grew up in a very poor area of Lebanon and have said your exposure to conflicts there played a part in the problems that you tackle in your work. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Fadel Adib: Yes, absolutely. I grew up in Lebanon after the Civil War ended. I remember it didn't make sense to me at the time, but I learned it afterwards. People who are in the generation of my parents, they would tell us, "May god send you good days”, or beautiful days. It's a very spiritual environment. The reason I did not understand that is because they witnessed a lot of wars growing up and they saw what was a beautiful country fall apart.

The unfortunate thing is, I grew up in a very nice time. But then war started happening again. I remember when I was taking the baccalaureate exams, which you take at the end of your high school, a battle started by a terrorist group literally one block away from my apartment. We could see them a block away and then we'd see an explosion happen. It was supposed to be a month where we were studying for these exams, and instead, we were sitting in the middle of the house and trying to study or maybe stay alive. I also witnessed the war in 2006. When you grew up in these environments, as a kid, you go to sleep and wonder, "Am I going to wake up tomorrow?"

For me, one, it taught me that no matter the conflicts that are around you, if you persevere, you can always make it out. That is great preparation for the world. But it also makes you realize, “What are the big problems? Why are these problems happening?” There's a number of them. For us, for example, education was always a big part. There's this culture of education. If you educate people, then you can steer them away from terrorist groups and you can also give them the resources that would allow them to survive and grow.

But also, food security is a problem. That relates to climate, because if you have a bad season, then these farmers who are out there are not able to make a living, and if they cannot make a living, then they cannot send their kids for education. That, again, starts creating these cycles. I grew up also in a coastal city so we were always worried about the sea level rise or about changes in climate.

All of these things, you realize they're interconnected. There is a political aspect of everything. But also you realize that if you can build solutions that will have a long-term impact, then you can mitigate a lot of these challenges, whether it's how climate change or food insecurity or lack of education leads to these conflicts further down the line. You want to be able to preempt them early on and ideally also try to stop them at a earlier stage.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes, I think those are really great points. The global interconnectedness, I think, is particularly important for us to think about in climate change. I was joking that if we solve climate change in Cambridge, it's not going to get the world very far. In other words, just for Cambridge. We can solve it in Cambridge for the world. I think a lot of the impact of climate change, if you will, is inflicted on less privileged countries by the wealthier countries in the world. I think we have a responsibility to think about how we devise solutions that really impact everyone in all sectors and in all corners of the world. As we work locally on climate change problems, I think many people don't appreciate the reverberating impacts globally. When we think about solutions, they have to be affordable, they have to be scalable, and they have to be deployable in areas of the world that don't have the infrastructure that we have here. If we want to affect global climate change, we have to be thinking much more broadly.

Fadel Adib: I will add to that actually. For example, think about solar energy harvesting or solar as a source of electricity. There's other reasons why building solar is good that people here might not realize.

In Lebanon, there's a lot of corruption. What that leads to is, for example, my parents get electricity maybe four hours a day from the central electricity that comes from the government. For a long time, they used to use gasoline motors which are bad for the environment. But even those were not able to keep up. What my parents recently did—and this is a trend in Lebanon—is they installed solar cells and solar batteries, and now they're powering more than 18 hours a day their apartment using the solar powering technology.

The reason this is possible is because of advances in solar energy harvesting, in battery storage, and so on. What that led, is it also led to this democratization of the ability to generate power. Making things affordable has this other aspect of giving people more control over their lives and over their destinies and making them less dependent on corrupt governments. When you do that, then the people have enough resources to live, flourish, educate themselves, and then that would lead to better generations of future politics and governments.

Sally Kornbluth: That's really interesting. I think also the democratization of technology allows the innovation by individual entrepreneurs. In other words, we're actually more effectively harnessing the collective in that way. Whereas if innovation is only in the hands of institutions or groups of people that have vast resources, you're only going to go in an individual direction. Whereas if you put the ability to generate power in a lot of individual hands, how that's deployed, how that might scale, is open to innovation by many.

Fadel Adib: I agree to that and I think that also goes even beyond climate. For example, if you think about politics. The Arab Spring, around 2011, people think of it now as a failure, but I think it's a very shortsighted approach to think about politics. Where did the Arab Spring start? It started in Tunisia. If you think about it there, they also used a lot of the tools, both there and in many of the other countries, they used a lot of the tools on peer-to-peer networking. These are areas that I'm familiar with. I remember in Lebanon when there was a mini-revolution, people used these tools. They were doing ad hoc networks to do these communications. These are very important tools that made them much more resilient to government intervention, so you're empowering the people. If you actually look at it, the Arab Spring started in Tunisia. Tunisia now is a fairly advanced democracy if you look at their constitution.

The reason it might not have picked up in some of the other places is because they tried to almost reproduce the same thing, but each of them is different. But this does not say that in 20, 30, 40 years from now, whatever happened 10 years ago or 12 years ago is going to have the repercussions. Because what we also don't realize is that the young people who are growing up and saw these tools, they're empowered. Their mind is different now and these things will come back. We should keep building them and democratizing tools because it will empower people, hopefully towards more democracy and towards the ability to define their own destinies and futures.

Sally Kornbluth: Actually, coming back to some of our earlier conversation about healthcare, some of your tools are also going to be critical for democratization of healthcare. When we think about monitoring for conditions that might be picked up in a routine physical, if you were really visiting doctors' offices routinely, that could really be detected through continuous monitoring by Wi-Fi signals. Even in very poor countries, as you know, many, many, many people have phones.

Fadel Adib: Absolutely. Wi-Fi is pervasive. When you take something and put it on a pervasive technology, you democratize it. When you do that, you can do, as you said, long-term monitoring and you can also detect diseases early. Many diseases are associated with changes with mobility or vital signs. You'd be able to bring those technologies to people rather than bringing people to high-end research centers in order for them to be tested.

Sally Kornbluth: I've heard you speak about that, your grandmother was widowed at a young age, raised her children alone, and instilled in all of them—sons and daughters—the importance of education. Thinking about your role at MIT then, you're doing all this innovative work, how do you view your responsibility as an educator, both to students here, but also how do we extend that beyond the borders of MIT?

Fadel Adib: That's a great question. Education is, of course, a big thing. As I mentioned before, in Lebanon, we think of it as the key to any success. If you want to succeed in my family, but also there's this general belief that education is power. There are some things that we can do locally, there are things that we can do locally-to-globally, and there are other things that we could do at the individual level.

For example, speaking about my grandma, when my grandfather died, that was in the late 1950s or early 1960s, her oldest child was seven years old. My mother was three. At that time, most places in the world, but definitely in the Middle East, they would want to try to marry off the kids very quickly, especially the females. My grandma said, "Nobody's getting married until you at least get a bachelor's degree and preferably a doctorate." I remember, when she passed away, I remember looking around the room and telling my family—she was the matriarch of the family, she was such a big thing—I looked at her CV and I saw 12 bachelor's degrees, 7 doctorates, 2 MDs, 2 professors, 3 MBAs. She instilled that in all of us.

One of the other things that I realized, and also I realized that after she passed away, I saw this Facebook post. There was this school principal that said that she just found out that my grandma passed away and that she will miss her. The reason is that my grandma, at the beginning of every year, she would go to that school, she would ask about a list of female students whose parents could not afford the tuition, and she would just pay their tuition so that they could get the education. I only found out after my grandma passed away.

Sally Kornbluth: Wow.

Fadel Adib: The only hint I had, and that was not even a hint, I figured that out in hindsight, is a few times she asked me to drive her to that school. I was like, "What is my grandma doing there?" She would just not say. There are things that you do locally. That is part of our culture.

There's also things that we do locally here at MIT. For example, I came from Lebanon to MIT. For me, that's a huge opportunity. I came right out of my undergrad and I did my PhD here and it opened so many doors for me. Today, when I'm looking and doing graduate admissions, I'm looking at people's trajectories. Not just what they've achieved, but what is the slope of their achievements? That's why my group ended up being super diverse with people from all around the world. Sometimes, almost from countries that there is a very small number of people at MIT. I'm looking at who stood out in their environment and then maybe if we bring them here, they will be able to shine in ways that when they were not given the resources, they couldn't. Even when I'm looking at admitting students from within the U.S., my group is also very diverse in that respect. In the sense that, you're looking again at people's trajectories. How did they stand out in their environments?

What we can do globally, one of the things that I like to do, is for each project, we try to create some form of video that is public-facing. The reason for that is, we're clearly excited about this. For broader reasons, yes—the technology and the science, there's all of that amazing curiosity—but there is an important thing in exposing the world to this. Similar to how writing papers takes time, creating these broader educational videos take time, but then they also get seen and shared a lot. While there's many ways of expanding the reach of education, for me, I personally enjoy it. I also go and read some of the comments that people put there. It's interesting because sometimes, these comments make us think about problems in different ways and that feeds back into our research. It's like getting community feedback but you're getting it from the broader public.

Sally Kornbluth: It's interesting, I'm sitting here listening to you and thinking, "You are so MIT." Your comments about the diversity of your group really resonate with the notion of potential over pedigree. Identifying those people who really have potential, that have thrived in whatever environment they're in, but if you move them to this incredible environment, they're going to do even more. The notion of how what we're doing here that's really curiosity-driven, always keeping in mind how that's going to impact the larger world and how we're going to attract more people to this curiosity-driven mission. You've had a fantastic journey from Lebanon to MIT. I can sense that you're super excited about the vistas ahead. Maybe give us one last comment on something you are really excited about coming up down the road.

Fadel Adib: I'll say two things. When I came first to MIT, I was thousands of miles away from home, but somehow I felt at home. I remember it almost felt like this place that I've been looking for for a long time and finally I found. Of course, the challenge was my family was in Lebanon. But you're surrounded by people who are so curious. I remember my advisor, I would tell her, for example, “We can't do this." She's like, "Why not?"

This fearlessness of thinking about the impossible, for me is amazing. Being driven by curiosity—this podcast is “Curiosity Unbounded”—we have intellectual conversations that are driven by curiosity. I find this to be amazing. I think that's one of the things that attracts students to my group. This ability of doing the impossible but also this fun culture where people are coming from very different backgrounds and exchanging them.

One thing that I really care about is also that the technologies that I'm building see the light of day. This is why during my PhD, I worked with my advisor to launch our startup which is in the healthcare space. This is why now I'm actually on sabbatical working on a second startup that aims to solve problems in the supply chain sector and retail sector with seeing all of the inflation happening. How do you cool this down using technologies and create resilient supply chains, which we realized was a big problem during Covid? I also love channeling that into my group. For example, MIT has the 100k Entrepreneurship Competition. My students who are working on oceans just participated in it because they want to commercialize our research there in food production. For example, they won a runner-up prize.

As much as I love the curiosity, it's very important for me to see this impacting the world. I feel that, in the beginning, we have to be in the driver's seat and push it. That's what excites me now, and especially being on sabbatical and working on a startup. This is something that I hope that we can keep doing. Being inspired by curiosity but then driving it to action at the end of the day.

Sally Kornbluth: That was fantastic. I enjoyed the conversation so much and all of your insights. So thank you for joining us today on Curiosity Unbounded.

Fadel Adib: Thank you for having me.

Sally Kornbluth: To our audience, thank you for listening to Curiosity Unbounded. I very much hope you'll join us again. I'm Sally Kornbluth. Stay curious.