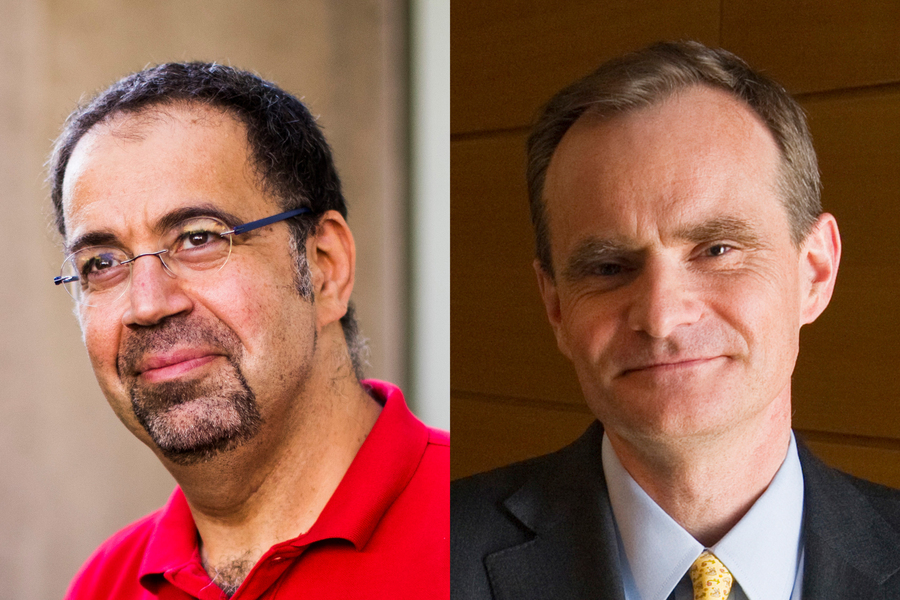

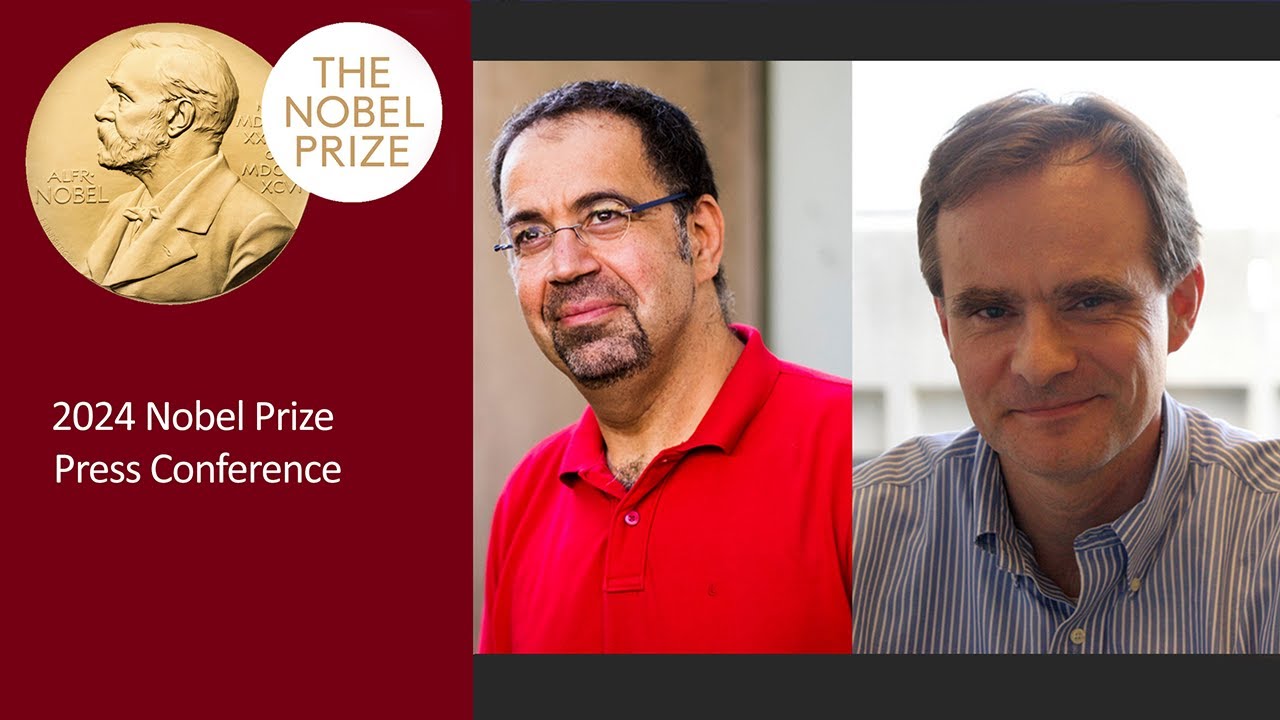

MIT economists Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson PhD ’89, whose work has illuminated the relationship between political systems and economic growth, have been named winners of the 2024 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. Political scientist James Robinson of the University of Chicago, with whom they have worked closely, also shares the award.

“Societies with a poor rule of law and institutions that exploit the population do not generate growth or change for the better,” the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences stated in the Nobel citation. “The laureates’ research helps us understand why.”

The long-term research collaboration between Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson, which extends back for more than two decades, has empirically demonstrated that democracies, which hold to the rule of law and provide individual rights, have spurred greater economic activity over the last 500 years.

“I am just amazed and absolutely delighted,” Acemoglu told MIT News this morning, about receiving the Nobel Prize. Separately, Johnson told MIT News he was “surprised and delighted” by the announcement.

MIT President Sally Kornbluth congratulated both professors at an Institute press conference this morning, saying that Acemoglu and Johnson “reflect a kind of MIT ideal” in terms of the excellence and rigor of their work and their commitment to collaboration. Their research, Kornbluth added, represents “a very MIT interest in making a positive impact in the real world.”

In their work, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson make a distinction between “inclusive” political governments, which extend political liberties and property rights as broadly as possible while enforcing laws and providing public infrastructure, with “extractive” political systems, where power is wielded by a small elite.

Overall, the scholars have found, inclusive governments experience the greatest growth in the long run. By contrast, countries with extractive governments either fail to generate broad-based growth or see their growth wither away after short bursts of economic expansion.

More specifically, because economic growth depends heavily on widespread technological innovation, such advances are only sustained when and where countries promote an array of individual rights, including property rights, giving more people the incentive to invent things. Elites may resist innovation, change, and growth to hold on to power, but without the rule of law and a stable set of rights, innovation and growth stall.

“Both political and economic inclusion matter, and they are synergistic,” Acemoglu said during the MIT press conference.

The scholarship of Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson has often been historically grounded, using the varying introduction of inclusive institutions, including the rule of law and property rights, to analyze their effects on growth.

As Acemoglu told MIT News, the scholars have used history “as a kind of lab, to understand how different institutional trajectories have different long-term effects on economic growth.”

For his part, Johnson said about the prize, “I hope it encourages people to think carefully about history. History matters.” That does not mean that the past is all-determinative, he added, but rather, it is essential to understand the crucial historical factors that shape the development of nations.

In a related line of research cited by the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson have helped build models to account for political changes in many countries, analyzing the factors that shape historical transitions of government.

Acemoglu is an Institute Professor at MIT. He has also made notable contributions to labor economics by examining the relationship between skills and wages, and the effects of automation on employment and growth. Additionally, he has published influential papers on the characteristics of industrial networks and their large-scale implications for economies.

A native of Turkey, Acemoglu received his BA in 1989 from the University of York, in England. He earned his master’s degree in 1990 and his PhD in 1992, both from the London School of Economics. He joined the MIT faculty in 1993 and has remained at the Institute ever since. Currently a professor in MIT’s Department of Economics, an affiliate at the MIT Sloan School of Management, and a core member of the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society, Acemoglu has authored or co-authored over 120 peer-reviewed papers and published four books. He has also advised over 60 PhD students at MIT.

“MIT has been a wonderful environment for me,” Acemoglu told MIT News. “It's an intellectually rich place, and an intellectually honest place. I couldn't ask for a better institution.”

Johnson is the Ronald A. Kurtz Professor of Entrepreneurship at MIT Sloan. He has also written extensively about a broad range of additional topics, including development issues, the finance sector and regulation, fiscal policy, and the ways technology can either enhance or restrict broad prosperity.

A native of England, Johnson received his BA in economics and politics from Oxford University, an MA in economics from the University of Manchester, and his PhD in economics from MIT in 1989. From 2007 to 2008, Johnson was chief economist of the International Monetary Fund.

“I think of MIT as my intellectual home,” Johnson told MIT News. “I am immensely grateful to the Institute, which has a special and creative atmosphere of rigorous problem-solving.”

Acemoglu and Robinson first published papers on the topic in 2000. The trio of Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson published their first joint study in 2001, an influential paper in the American Economic Review detailing their empirical findings. Acemoglu and Robinson published their first co-authored book on the subject, “Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy,” in 2006.

Acemoglu and Robinson are co-authors of the prominent book “Why Nations Fail,” from 2012, which also synthesized much of the trio’s research about political institutions and growth.

Acemoglu and Robinson’s subsequent book “The Narrow Corridor,” published in 2019, examined the historical development of rights and liberties in nation-states. They make the case that political liberty does not have a universal template, but stems from social struggle. As Acemoglu said in 2019, it comes from the “messy process of society mobilizing, people defending their own liberties, and actively setting constraints on how rules and behaviors are imposed on them.”

Acemoglu and Johnson are co-authors of the 2023 book “Power and Progress: Our 1,000-Year Struggle over Technology and Prosperity,” in which they examine artificial intelligence in light of other historical battles for the economic benefits of technological innovation.

Johnson is also co-author of “13 Bankers” (2010), with James Kwak, an examination of U.S. regulation of the finance sector, and “Jump-Starting America” (2021), co-authored with MIT economist Jonathan Gruber, a call for more investment in scientific research and innovation in the U.S.

Gruber, as head of the MIT Department of Economics, praised both scholars for their accomplishments.

“Daron Acemoglu is the economists’ economist,” Gruber said. “Daron is a throwback as an expert across a broad swath of fields, mastering topics from political economy to macroeconomics to labor economics — and he could have won Nobels in any of them. Yet perhaps Daron’s most lasting contribution is his essential work on how institutions determine economic growth. This work fundamentally changed the field of political economy and will be an enduring legacy that forever shapes our thinking about why nations succeed — and fail. At MIT, we recognize Daron not just as an epic scholar but as an epic colleague. Despite being an Institute Professor who is freed from departmental responsibilities, he teaches many courses every year and advises a huge share of our graduate student body.”

About Johnson, Gruber said: “Simon Johnson is an amazing economist, a terrific co-author, and a wonderful person. No one I know is better at translating the esoteric insights of our field into the type of concise explanations that bring economics to the attention of the public and policymakers. Simon doesn’t just do the fundamental research that changes how the profession thinks about essential issues — he speaks to the hearts and minds of those who need to hear that message.”

Agustin Rayo, dean of MIT’s School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, home to the Department of Economics, heralded today’s Nobel Prize as well.

“This award is deeply deserved,” Rayo said. “Daron is the sort of economist who shifts the way you see the world. He is an extraordinary example of the transformative work that is generated by MIT's Department of Economics.”

“All of us at MIT Sloan are very proud of Simon Johnson and Daron Acemoglu’s accomplishments,” said Georgia Perakis, the interim John C. Head III Dean of MIT Sloan. “Their work with Professor Robinson is important in understanding prosperity in societies and provides valuable lessons for us all during this time in the world. Their scholarship is a clear example of work that has meaningful impact. I share my heartiest congratulations with both Simon and Daron on this incredible honor.”

Previously, eight people have won the award while serving on the MIT faculty: Paul Samuelson (1970), Franco Modigliani (1985), Robert Solow (1987), Peter Diamond (2010), Bengt Holmström (2016), Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo (2019), and Josh Angrist (2021). Through 2022, 13 MIT alumni have won the Nobel Prize in economics; eight former faculty have also won the award.