Where do democratic states with substantial personal liberty come from? Over the years, many grand theories have emphasized one specific factor or another, including culture, climate, geography, technology, or socioeconomic circumstances such as the development of a robust middle class.

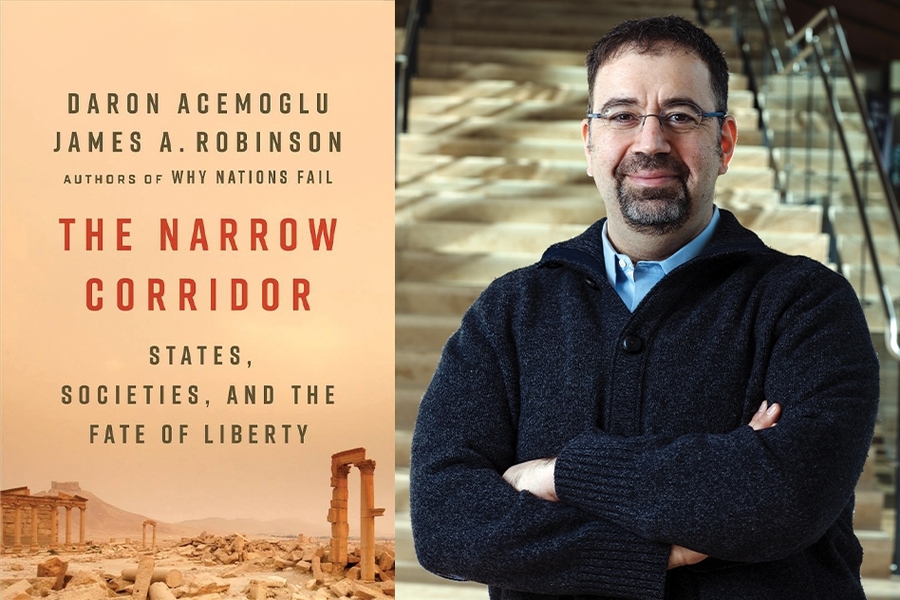

Daron Acemoglu has a different view: Political liberty comes from social struggle. We have no universal template for liberty — no conditions that necessarily give rise to it, and no unfolding historical progression that inevitably leads to it. Liberty is not engineered and handed down by elites, and there is no guarantee liberty will remain intact, even when it is enshrined in law.

“True democracy and liberty don’t originate from checks and balances or from clever institutional design,” says Acemoglu, an economist and Institute Professor at MIT. “They originate [and are sustained] in the much more messy process of society mobilizing, people defending their own liberties, and actively setting constraints on how rules and behaviors are imposed on them.”

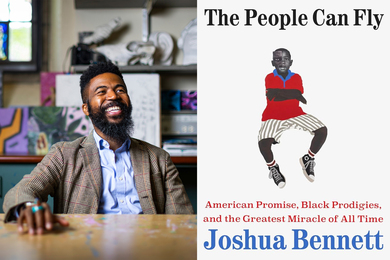

Now Acemoglu and his longtime collaborator James A. Robinson, a political scientist at the University of Chicago, have a new book out propounding this thesis. “The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty,” published this week by Penguin Random House, examines how some states emerged as beacons of liberty.

The crux of the matter, to Acemoglu and Robinson, is that liberal-democratic states exist in between the alternatives of lawlessness and authoritarianism. The state is needed to protect people from domination at the hands of others in society, but the state can also become an instrument of violence and repression. When social groups contest state power and harness it to help ordinary citizens, liberty expands.

“The conflict between state and society, where the state is represented by elite institutions and leaders, creates a narrow corridor in which liberty flourishes,” Acemoglu says. “You need this conflict to be balanced. An imbalance is detrimental to liberty. If society is too weak, that leads to despotism. But on the other side, if society is too strong, that results in weak states that are unable to protect their citizens.”

From the “Gilgamesh problem” to the “narrow corridor”

Following the English political theorist John Locke, Acemoglu and Robinson define liberty by writing that it “must start with people being free from violence, intimidation, and other demeaning acts. People must be able to make free choices about their lives and have the means to carry them out without the menace of unreasonable punishment or draconian social sanctions.”

This has been a nearly eternal concern, the authors note: Gilgamesh, per the ancient epic, was a king who “exceeded all bounds” in society. The need to curb absolute power is something the authors call the “Gilgamesh problem,” one of several coinages in the book. Another is the “cage of norms,” the condition where society, in absence of a state, organizes itself to avoid extensive violence — but only through restrictive social arrangements.

States, by becoming the guarantors of liberty, can break the repressive cage of norms. But social groups must curb state power before it too stifles freedom. When state capacity and society develop in tandem, the authors call this the “Red Queen effect,” alluding to a race in Lewis Carroll’s “Through the Looking Glass.” This “race,” if balanced enough, occurs in the “narrow corridor” where liberty-supporting states can exist.

Acemoglu and Robinson examine ancient cases of political reform from Athens to the Zapotec state, and they locate liberty’s largest direct wellspring in the early Middle Ages. Germanic tribes had quasidemocratic assemblies; meanwhile some leftover administrative structures of the Roman empire still existed alongside those of the Christian church. When the Frankish king Clovis created a “fusion of Roman state structure with the norms and political institutions of the Franks” in 511, the authors write, some parts of Europe were “at the entryway to the corridor” toward liberty.

To be sure, there was a “gradual, painful historical process” to be played out; it was another 700 years before King John of England signed the Magna Carta in 1215, a watershed for the distribution of lawful power beyond the throne.

Still, state structures being grafted onto a mechanism for representing society, through assemblies, meant both state and society could expand their power. As Acemoglu and Robinson put it, this “fortuitous balance” effectively “put Europe into the corridor, setting in motion the Red Queen effect in a relentless process of state‐society competition.” Eventually, European democracies evolved.

“Liberty is fragile”

That Europe took the lead in creating liberty-granting states was not inevitable, Acemoglu and Robinson emphasize. Almost 3,000 years ago, they note, ancient China was organized into city-states, and one influential political advisor of the time wrote that “the people are masters of the deities.” But by the fourth century B.C.E., spurred on by the politician and theorist Shang Yang, Chinese rulers built a much more powerful state, which became the Qin empire. Despite many potential moments of reform, detailed in “The Narrow Corridor,” China’s state has largely remained much more powerful than its social interests.

Moreover, Acemoglu suggests, the longer a despotic state exists, “the more self-reinforcing it becomes.” He adds: “The more it takes root, the more it sets up a hierarchy which is hard to change, and the more it weakens society. … That’s why I think dreams of China smoothly converting to a democratic system have been misplaced — [it’s had] 2,500 years of state despotism.”

The account of the U.S. in “The Narrow Corridor” also takes a long view, albeit over a much shorter period. The U.S. Constitution and the architecture of government developed in the late 18th century, Acemoglu and Robinson write, was a “Faustian bargain” created by Federalists to limit both absolute power and popular power. This structure, they believe, especially its emphasis on states’ rights, “meant that the federal state remained impaired in some important dimensions. For one, it obviously didn’t protect slaves and later its African American citizens from violence, discrimination, poverty, and dominance.”

Acemoglu and Robinson also believe that focusing too much on “the brilliant design of the Constitution” is problematic because it “ignores the critical role that society’s mobilization and the Red Queen [effect] played at every turn. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights … were the result of the tussle between elites and the people.” The expansion of U.S. rights and liberties has emerged intermittently — following the Civil War, the civil rights movement, and the women’s rights movement, among other things. But these liberties can also recede if political counter-movements become effective enough.

“That is the sense in which liberty is fragile,” Acemoglu says. “If you thought liberty depended on clever designs, you’d have thought we would find the perfect design that protects liberty all the time. But if you think it depends on this messy process, then it’s a much more contingent and troubled existence.”

Facing the “urgent challenges for us today”

“The Narrow Corridor” examines many additional cases of state-building in history, from India and Africa to Scandinavia. It also builds on a body of work Acemoglu and Robinson have produced examining the relationships between society, state institutions, and growth. That includes the books “Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy” (2006) and “Why Nations Fail” (2012). The two scholars have also co-authored 36 published papers on these topics (some with additional co-authors).

Acemoglu has also published widely on labor economics, the impact of technology on work and growth, and macroeconomic dynamics. He was named as one of MIT’s 12 Institute Professors this summer and has been on the faculty of the Department of Economics since 1993.

As the authors view it, their account of liberty stands in contrast to many other models. The close of the Cold War helped generate the idea of a geopolitical “end of history,” in which states would converge on a liberal-democratic model. That notion did not closely forecast subsequent developments. Neither did postwar theories of modernization that posited a standardized path to democratic prosperity for the developing world.

“There are multiple destinations countries can be headed to,” Acemoglu says. “There is nothing ephemeral about a despotic state or a weak state, and there is no ineluctable process that’s going to take every country smoothly toward some sort of liberty at all.”

Moreover, Acemoglu says, “Our argument is not a culturally deterministic one.” He adds: “There are views that are very economistic. … Ours is a view that emphasizes the role of agency by individuals and society, and maintains that different social organizations lead to different outcomes. It’s also not geography-based. I think there are a lot of differences from [other] theories.”

Scholars have praised “The Narrow Corridor.” Joel Mokyr, a historian at Northwestern University, has called it “a magisterial book of immense insight and learning,” which “draws a chilling conclusion every thinking person should be aware of: Liberty is as rare as it is fragile, wedged uneasily between tyranny and anarchy.”

Today’s politics have also generated abundant discussion about the future of governance and democracy. In this vein, Acemoglu says, “The Narrow Corridor” is an engagement with the past meant to illuminate the present.

“We need to think about history,” Acemoglu says. “We are writing this book because we think it’s relevant to the urgent challenges for us today. Creating the right sort of political balance, and mobilizing society while not disempowering laws and institutions, are completely first-order challenges we face today. I hope our perspective will shed some light on those issues.”

![“Relatively small shocks can become magnified and then become shocks you have to contend with [on a large scale],” says MIT economist Daron Acemoglu.](/sites/default/files/styles/news_article__archive/public/images/201604/MIT-macroeconomy.jpg?itok=LFmXBcZ3)