MIT’s faculty meeting on Wednesday had a special guest: Graduate student Alvin Harvey SM ’20 spoke on behalf of students, faculty, and staff who have been drawing attention to MIT’s historical relationship with Indigenous peoples and examining how the Institute can build durable support for its Indigenous community.

One vehicle for that work has been course 21H.283 (The Indigenous History of MIT), launched in the spring of 2021. Last Wednesday, Harvey, a PhD student in MIT’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, outlined the kinds of topics 21H.283 has explored, while making a direct and heartfelt call for the Institute to rectify what he asserted has been “the intentional erasure of the Indigenous presence at MIT” in the Institute’s past.

“Your positions as intellectual leaders at MIT allow you to be brave, to make the changes necessary to repair the relationship with Indigenous people,” Harvey told the faculty at the online meeting. “This course is a part of that work.”

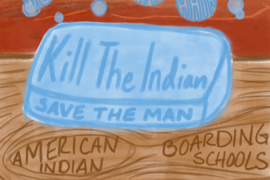

As students in 21H.283 have examined, MIT’s history intersects in multiple ways with the broader history of oppression of Native Americans. MIT’s third president, Francis Amasa Walker, who led the Institute from 1881 to 1897, served as U.S. commissioner of Indian affairs in the early 1870s. Walker was a staunch advocate of the reservation system — in which Native Americans were forcibly removed to reservations, in the midst of conflict, wars, and massacres, often in explicit violation of treaties the U.S. had previously signed.

Through the Morrill Act of 1862 (updated in 1890), which established land grants —including land taken from Native Americans — for U.S. universities, the federal government also gave the state of Massachusetts land scrip, the right to take possession of land or sell it. The state opted to sell, and used the proceeds to help fund the creation of MIT and what is today the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

“These are very heavy topics,” said Harvey, himself a member of the Navajo Nation. “Every time we discussed these in our course, we felt that pain and that frustration.”

A “responsibility” to support, share, and learn

In a July 2020 letter to the MIT community, President L. Rafael Reif first announced the Institute’s expanded commitment to research about the history of Native Americans and MIT, citing the need to “establish stronger, lasting ties to Native American alumni and communities.” In its first semester, 21H.283 was taught by Craig Wilder, the Barton L. Weller Professor of History at MIT. During the 2021-2022 academic year, the course has been taught by David S. Lowry ’03, Distinguished Fellow in Native American Studies.

Lowry was present at the Wednesday faculty meeting, as were many course participants, including Sarah Acolatse, a senior majoring in biological engineering; Alona Bach, a PhD candidate in MIT’s Program in Science, Technology, and Society (STS); Luke Bastian ’21, an MEng candidate in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering; Nancy Dalrymple, a staff adviser to the Native American Students Association; Shannon Hasenfratz, an MCP candidate in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning; Nina Lytton SM ’84; Alyssa Spencer, a senior majoring in chemical engineering; and Ece Turnator, a humanities and digital scholarship librarian at MIT.

Among other things, students in 21H.283 have started the gradual process of building a directory of Native American alumni of MIT, having found that even basic information about such matters was difficult to obtain over much of the Institute’s history. Harvey also cited the work of Dalrymple, whose research interest in the Morrill Act has helped generate further interest in the topic among students and the MIT administration.

Reif met with class participants at the end of each of the last two semesters, starting in the spring of 2021. In a letter to the MIT community last Tuesday, Reif announced several additional measures the Institute is taking to “advance Indigenous scholarship and support for our indigenous community,” including a new faculty position and a pledge of funding to support Indigenous community-building efforts at MIT.

Moderating Wednesday’s meeting, Reif praised Harvey’s “spectacular” presentation, adding that MIT was “very, very proud that you are one of our students.”

In his remarks, Harvey emphasized that MIT’s position as a beneficiary of the Morrill Act meant that the Institute, and other universities, have an ethical imperative today to act in response to their past.

“These Indigenous people were killed for their land,” Harvey said. “As a land grant college, MIT has an obligation to support Indigenous people and students.”

In general, Harvey said, “Public and land grant universities have a responsibility to continue to provide opportunities for Native American students while working to appropriately and respectfully serve as ready and willing partners to help address challenges and needs. And public and land grant universities will share and continue to learn from the history of Native Americans, whose lives, traditions, and cultures are inextricably linked to their own history, and the diverse character of the United States.”

While many of Harvey’s remarks focused on the need to acknowledge a painful past and the burden Native Americans often face in having to initiate social change, he did sound several optimistic notes about the opportunities awaiting MIT and Indigenous peoples.

“There is limitless potential in making a better world through partnerships between MIT and Indigenous nations, people, and communities,” Harvey said.

New set of actions from MIT

MIT has moved to further realize that potential in 2022. In his letter to the MIT community, Reif specified several new measures the Institute is taking.

To bolster research and teaching, MIT is creating a tenure-track faculty position in Native American studies, starting in the 2023-24 academic year, and adding two new positions in the MLK Visiting Professors and Scholars Program, at least one of which will be allocated annually to an expert in Native American studies. For the next two academic years, the Institute will also provide financial support for two graduate fellowships in the MIT Indigenous Language Initiative (MITILI), a master’s program launched in 2003 that helps protect endangered languages.

Additionally, the Institute will fund a study about Francis Amasa Walker and his role in justifying the reservation system. “MIT has a responsibility to unearth and shine a light on that history so that we may learn from it,” Reif wrote.

MIT is also working with Massachusetts officials to examine the status of its annual Morrill Act payments from the state, which ceased without explanation in 2008. It is possible those payments may resume; until they do, MIT has pledged to allocate an equivalent annual sum to Indigenous activities on campus. The Institute will provide an initial one-time sum of $50,000, apart from current support.

MIT Chancellor Melissa Nobles and Institute Community and Equity Officer John Dozier will chair a working group — “taking special care to ensure that our Native community is present and deeply engaged,” Reif wrote — to assess multiple issues, including the best use of those funds. By the end of 2022, the working group will also recommend to Reif whether MIT should formulate a land acknowledgment statement; previously, in 2019, members of MIT’s Indigenous community, working with staff and officials from local tribal communities, drafted and released a statement. The group will additionally evaluate the possibility of a statement about MIT’s general relationship with Indigenous communities.

The working group will also examine the best practices the administration can use to sustain “open, regular communication” with Native American communities on campus and in the local area.

The MIT Solve conference is also continuing its Indigenous Communities fellowship, launched in 2018, which supports innovators working with Indigenous peoples. So far the program has supported 28 fellows, and the work of the 2020 and 2021 Indigenous Communities Fellows will be highlighted at the upcoming Solve at MIT, from May 5 to 7.

For his part, Harvey noted that MIT has already made some recent advances in support of its Native American community. In September 2020, Reif announced that MIT would rename the Columbus Day holiday as Indigenous Peoples Day. Additionally, working with students from MIT’s chapter of the American Indian Science and Engineering Society as well as the campus’ Native American Student Association, the Institute created a dedicated space in Building W31 for Indigenous community members, which opened on Indigenous Peoples Day in 2021.

“There are things to celebrate, and us getting an Indigenous Peoples center, [a] gathering space for students, is one of the things that we’re really proud of. … Our students make use of that every day,” Harvey said. “It’s amazing to have a place that is not so much MIT but is Indigenous, and feels like home.” He observed as well that MIT’s adoption of the term Indigenous Peoples Day has been “incredibly important to us.”

“Truth-telling that we need to do”

In his remarks, Harvey also called himself “very fortunate to participate this past year” in 21H.283, and noted that many Indigenous community members at MIT in the past, not just those on campus today, have worked to surface these issues at the Institute.

“I especially recognize Indigenous students that came before me, decades before me, who built a foundation up to allow us to have these types of conversations,” Harvey said. “We look forward to working with the leaders of MIT on turning these initial steps into big and intentional steps.”

The discussion also featured a question-and-answer session. Kenneth Manning, the Thomas Meloy Professor of Rhetoric at MIT and a faculty member in both STS and Comparative Media Studies/Writing, praised Harvey’s “wonderful talk,” and said the Institute was moving in the “right direction” with the steps it is taking. Still, Manning added, “I think it is true that MIT has really overlooked the state of Native Americans, and I hope that we can rally around the effort Craig and David have put forth, and remedy this.”

Lowry, who also spoke during the question-and-answer session, remarked on the need to bolster undergraduate education about colonialism generally, and said that the further establishment of Native American studies at MIT would mean that “rates of student harm will go down, and rates of people within MIT feeling alienated will go down.”

Facing hard truths, Lowry added, would help MIT develop a more cohesive sense of community.

“When people speak truth in the MIT community, don’t assume that that is antagonism. Don’t assume that people want to pick fights,” Lowry said. “This is a truth-telling that we need to do within the MIT community that really creates the future of MIT, where we all, across communities, across disciplines, can begin to care for one another.”

Reif, for his part, added that Harvey’s remarks were “very beautifully delivered. We will continue to move forward together.”