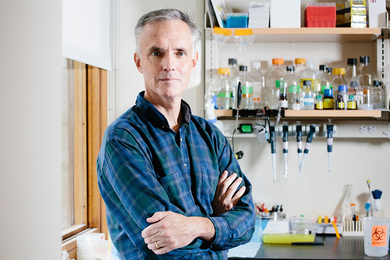

Professor Hal Abelson has dedicated his career to making information technology more accessible to all and empowering people — kids, in particular — through computer science. But his storied career in computer science began with Abelson coming to MIT in 1969 to pursue his interest in mathematics.

“The thing I like to remind students of is that they don’t have to know what they are going to do with the rest of their life,” Abelson says. “I get a lot of emails from students in high school asking what they should be studying, and I say, ‘Gee you should be trying to do something that doesn’t even exist yet!’”

Today Abelson’s work is focused on democratizing access to computer science and empowering children by showing them that they can have an impact on their community through the power of technology. Throughout his career, Abelson has played an important role in numerous educational technology initiatives at MIT, including MIT OpenCourseWare and DSpace, and as the co-chair of the MIT Council on Educational Technology. He is also a founding director of Creative Commons, Public Knowledge, and the Free Software Foundation.

Today, his App Inventor platform, which enables adults and kids to create their own mobile phone applications, has over 1 million active users.

“Making education — both content and tools — openly accessible might seem like an obvious idea now, but it was truly unthinkable until Hal Abelson made it so, says Sanjay Sarma, the Fred Fort Flowers and Daniel Fort Flowers Professor of Mechanical Engineering and former vice president of MIT Open Learning. “Millions of students receive the gift of learning today on their computers and smart phones, and they may never realize that it all began with an outrageously creative and courageous break from the past. Thank you, Hal!”

When smartphones began entering the market in 2008, Abelson was on sabbatical at Google. The potential of these powerful, yet small and personalized computing devices inspired him to create a platform that could enable children and adults with no background in computer science to create mobile phone applications. Abelson recalls that during his time in the lab of late Professor Emeritus Seymour Papert, he and his colleagues would dream about the game-changing potential of providing children access to smaller, more personalized, and more affordable computers.

When Abelson came up with the idea for the App Inventor platform, he recalls thinking “mobile phones are going to have a tremendous impact on how people interact with computers. I thought to myself, wouldn’t it be cool if kids could actually create programs with these mobile phones?”

The inspiration for Abelson’s work aimed at democratizing access to computing stems in large part from his early days as a graduate student at MIT in the late 1960s and 1970s.

As luck would have it, upon matriculating at MIT, Abelson ran into a high school friend during a student protest, who recommended he check out the AI Lab (the precursor to the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory). There Abelson met Papert, a pioneering computer scientist known for his view that computation could be used as a framework in teaching. Abelson had just heard Papert deliver a lecture on his vision, and Abelson jumped at the chance to work with Papert.

During his time as a researcher in Papert’s lab, Abelson worked on Logo, the first programming language for children, which allowed users to program the movements of a turtle. Abelson went on to direct the first implementation of Logo for Apple computers, which made the programming language widely available on personal computers beginning in 1981.

After graduating from MIT, Abelson became an instructor in the MIT Department of Mathematics, assisting in a computer science course taught by the late Professor Emeritus Robert Fano, while also continuing his research with Papert. At the end of the semester, Fano emphasized to his students that computer programs and systems were really all about communication between people. It was a radical concept for the 1970s and one that Abelson took to heart.

Computing as a means of enabling human communication was a key concept that Abelson and Gerald Sussman, the Panasonic Professor of Electrical Engineering, used to develop their course, “Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs.” Through the publication of a popular accompanying textbook and videos of their lectures, the course is widely seen as having influenced computer science curricula around the world.

While continuing his work as a computer science researcher and educator, Abelson remained focused on finding new ways to help improve access to information technology, as he strongly believed in the importance of educating people of all ages about the power they have to enact change through using computer science.

Today App Inventor has expanded significantly, and participants are creating apps on everything from tools to help people reduce their carbon footprints to apps aimed at improving mental agility, and mental health and wellness. Abelson notes that when young people are provided with the tools to create meaningful technology they can come up with some incredible inventions. For example, students at an elementary school in Hong Kong developed an app aimed at helping aging citizens with dementia by providing users with location information and other services when they need assistance. What makes the app stand out, Abelson explains, is that when users want voice instructions they are delivered using the recorded voice of a member of their family, an example of the unique perspective kids can provide when creating computational tools.

Abelson and his colleagues are now planning for the next stage of the App Inventor platform, including creating a foundation that will be focused on not only providing students and educators with tools to create mobile apps, but also an extensive K-12 curriculum and more personalized tools aimed at helping teachers use the App Inventor platform in their classrooms.

Abelson explains that a key concept behind App Inventor is an idea called computational action. “Computational action is not just computational thinking, but really realizing that someone can use computational tools to do something that has an impact on their life and their family’s life.”

In the future, Abelson would also like to help empower kids to use AI. He envisions a future where children around the world are allowed to experiment with and use AI technologies in the same way that children have helped design experiments that end up onboard NASA space missions.

“Part of democratizing access to computation is realizing that, gosh, even kids can do it. And even kids can do serious things. That’s part of my vision for the future, and that’s what I would like to see the App Inventor Foundation involved in,” says Abelson. “I think we can really help make the information infrastructure participatory so that even kids can be part of that. Kids are people too!”