Independence movements are complicated. Consider Burma (now Myanmar), which was governed as a province of British India until 1937, when it was separated from India. Burma then attained self-rule in 1948. Amid some straightforward demands for autonomy from India, one Burmese nationalist, a Buddhist monk named U Ottama, had a different vision: He wanted his country to break free of Britain but remain part of India, until Burma could become independent.

Why would a Burmese Buddhist want independence from one country, only to seek a union with a much bigger — and majority Hindu — neighbor to achieve this?

“At the heart of Ottama’s politics lay a spiritual and civilizational geography that framed his argument for Burma’s unity with India,” says MIT historian Sana Aiyar, who is working on a book about Burma and India at the time of the independence movement. “As Burmese nationalists increasingly defined their nationhood in religious terms to demand the separation of Burma from India, U Ottama insisted that since India was the birthplace of Buddhism, Burma was inextricably linked with India.”

That this vision found an audience hints at the extensive connections between Burma and India. From 1830 through 1930, an estimated 13 million Indians passed through Burma — the majority of whom were migrant or seasonal laborers — making the city of Rangoon a cosmopolitan capital. Many stayed and married Burmese women — which helped spark an anti-immigrant, anti-Indian backlash that became one driver of Burma’s independence movement.

The complexity of the political fault lines of Burmese self-rule makes the topic a natural for Aiyar. A historian of the Indian diaspora, she generally examines how migration, nationalism, and religion have fed into 20th-century anticolonial politics.

Aiyar’s work has another distinctive motif. She specializes in illuminating figures like U Ottama, who were once influential but are little-known now.

“The core interest that I have is in political history,” says Aiyar, who was awarded tenure earlier this year. “But I’m interested less in the big event, the obvious narrative, and the big leaders. What has always fascinated me are the alternatives, the possibilities that did not get a chance to see complete fruition — the person who didn’t become ‘Gandhi,’ didn’t quite get the same following, but seems to have really mattered in the moment.”

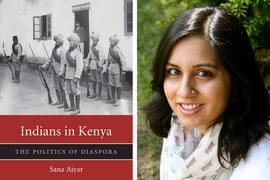

In Aiyar’s 2015 book “Indians in Kenya: The Politics of Diaspora,” for instance, a key figure is Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee, a trader who, in another complex scenario, became a leader for Indian rights in British-occupied Kenya, even as many Indians never became fully aligned with the British or other Kenyans. But even people strolling through Jeevanjee Gardens, a park in central Nairobi, are unlikely to know much about its namesake.

“In all of my research, I’ve been following those kinds of elusive figures whose long, shadowy presence emerges in fragments in colonial and national archives,” Aiyar says. “They allow me to ask questions about the dilemmas and dynamics of the moment.”

Old and new in Delhi

Aiyar grew up in Delhi, in an intellectually minded family; her mother was a journalist, and her father a diplomat and politician.

“Even around the dining table, history and politics were always there. It was just part of growing up,” Aiyar says.

History and politics were always there in Delhi, too.

“Growing up in a city like Delhi … you’re surrounded by history,” Aiyar notes. “It’s almost impossible to look out of the window when you’re driving anywhere in Delhi without seeing historical sites and the outcomes of historical processes in people’s everyday lives.”

Aiyar received a BA in history at St. Stephen’s College of Delhi University and then a BA and MA in history at Jesus College in Cambridge, U.K. Aiyar’s stay in England was also the first time she had observed Indians abroad, which made a significant impression on her: “I noticed the way the diaspora made itself visible in Britain, especially in a multicultural state, was not by presenting itself as secular, but through religion,” she says.

At that time, politics within India had also taken a turn away from the secularism of the post-independence era, opening up, Aiyar says, “the question of what defined Indian nationhood, who is Indian.”

Aiyar attended Harvard University for her PhD in history, originally planning a dissertation about the rise of Hindu nationalism among the Indian diaspora in Britain. She started her research examining the first group in Britain to assert their right to belonging through religion — Indians who had arrived in the U.K. from East Africa in the 1960s. Aiyar became fascinated by the migration of Indians to Kenya in the 19th and 20th centuries, a little-known history at the time, and the relationship they had to both sides of anticolonial politics. Visiting Kenyan archives made clear there was abundant material on hand involving Jeevanjee and many other figures.

“Methodologically it always comes back to the archives, where I find a person or an event that calls into question what we think we know about the past,” Aiyar says. “I wonder what is this person doing there, and then I start digging up all the files I can find. I am really an archive rat and the thing about dealing with South Asian history in the colonial period is, there’s just files and files and files of documents — the Brits really liked their paperwork! If one likes the joy of discovery in the archives, there’s so much to piece together.”

After completing her dissertation, Aiyar took a postdoc position at Johns Hopkins University, then served on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin at Madison for three years. She joined MIT in 2013.

Partition project

At MIT, Aiyar appreciates her students — “They are curious, they are open-minded, and a lot of fun to teach” — and enjoys being part of a history faculty with global scope.

“One of the things I absolutely love about being here is how international our world history section is,” she says. “For a small department, we really pack a punch. We have every region of the world represented with top-rate scholars.”

While teaching, Aiyar is pursuing two long-term research efforts. One project is about the encounters between African soldiers and civilians during World War II, in Burma and India. The other, about Burmese independence and titled “India’s First Partition: Recovering Burma’s South Asian History,” is her second book project.

The title is an indirect reference to the division of Pakistan from India in 1947, which almost exclusively holds claim to the world “partition” in South Asian history. But Aiyar’s contention is that this term applies to the separation of Burma from India in 1937.

“It is a partition,” Aiyar says. “It’s the very first time a carceral border is created in South Asia, and immigration laws are introduced that literally prevent the millions who moved in and out of Burma from crossing over without paperwork. The border creates a surveillance state. All of this takes place a full decade before Pakistan is created. … I am arguing that 1937 was the first partition of India.”

In writing the book, Aiyar is also digging into literature, diaries, and other documents to reconstruct daily life in Burma and show the many interconnections among people of Burmese and Indian heritage.

“The history of the mundane, the everyday, I think will really complement the political history of conflict and tension,” Aiyar says. “I’ve always been interested in how people live together with difference.”

Or not live together, as the case may be. In South Asia or elsewhere, then and now, as Aiyar recognizes, separatist identity politics can also be a powerful animating force for individuals and political factions.

“We can look to history to understand what these questions are about and why people are that invested,” Aiyar says. “I’ve always found history is a really useful way to understand what is going on in the contemporary world.”