“I went into the military right after high school, mostly because I didn’t really see the value of academics,” says Air Force veteran and MIT sophomore Justin Cole.

His perspective on education shifted, however, after he experienced several natural disasters during his nine years of service. As a satellite systems operator in Colorado, Cole volunteered in the aftermath of the 2013 Black Forest fire, the state’s most destructive fire at the time. And in 2018, while he was leading a team in Okinawa conducting signal-monitoring work on communications satellites, two Category 5 typhoons barreled through the area within 26 days.

“I realized, this climate stuff is really a prerequisite to national security objectives in almost every sense, so I knew that school was going to be the thing that would help prepare me to make a difference,” he says. In 2023, after leaving the Air Force to work for climate-focused nonprofits and take engineering courses, Cole participated in an intense, weeklong STEM boot camp at MIT. “It definitely reaffirmed that I wanted to continue down the path of at least getting a bachelor’s, and it also inspired me to apply to MIT,” he says. He transferred in 2024 and is majoring in climate system science and engineering.

“It’s a lot like the MIT experience”

MIT runs the boot camp every summer as part of the nonprofit Warrior-Scholar Project (WSP), which started at Yale University in 2012. WSP offers a range of programming designed to help enlisted veterans and service members transition from the military to higher education. The academic boot camp program, which aims to simulate a week of undergraduate life, is offered at 19 schools nationwide in three areas: business, college readiness, and STEM.

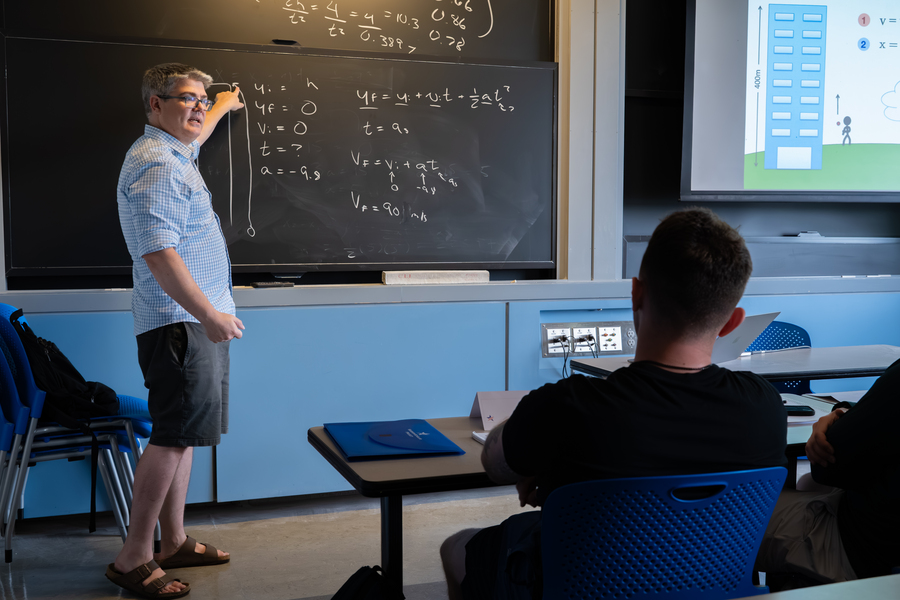

MIT joined WSP in 2017 as one of the first three campuses to offer the STEM boot camp. “It was definitely rigorous,” Cole recalls, “not getting tons of sleep, grinding psets at night with friends … it’s a lot like the MIT experience.” In addition to problem sets, every day at MIT-WSP is packed with faculty lectures on math and physics, recitations, working on research projects, and tours of MIT campus labs. Scholars also attend daily college success workshops on topics such as note taking, time management, and applying to college. The schedule is meticulously mapped out — including travel times — from 0845 to 2200, Sunday through Friday.

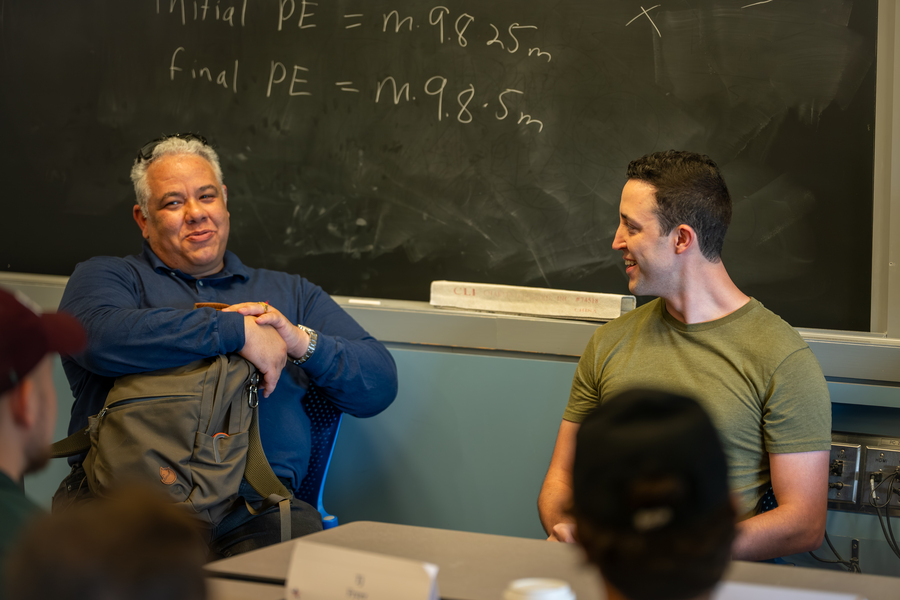

Michael McDonald, an associate professor of physics at the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, and Navy veteran Nelson Olivier MBA ’17 have run the MIT-WSP program since its inception. At the time, WSP wanted to expand its STEM boot camps to other universities, so a Yale astrophysicist colleague recruited McDonald. Meanwhile, Olivier’s former Navy SEAL Team THREE teammate — who happened to be the WSP CEO — convinced Olivier to help launch the program while he was at the MIT Sloan School of Management, along with classmate Bill Kindred MBA ’17.

Now in its 10th year, MIT-WSP has hosted over 120 scholars, 93 percent of whom have gone on to attend schools like Stanford University, Georgetown University, University of Notre Dame, Harvard University, and the University of California at Berkeley. MIT-WSP alumni who have graduated now work at employers such as Meta, Price Waterhouse Coopers, Boeing, and BAE Systems.

Translating helicopter repairs to Newton’s laws

McDonald has a lot of fun teaching WSP scholars every summer. “When I pose a question to my first-year physics class in September, no one wants to meet my eyes or raise their hand for fear of embarrassing themselves,” he says. “But I ask a question to this group of, say, 12 vets, and 12 hands shoot up, they are all answering over each other, and then asking questions to follow up on the question. They are just curious and hungry, and they couldn’t care less about how they come off. … As a professor, it’s like your dream class.”

Every year, McDonald witnesses a predictable transformation among the scholars. They start off eager enough, however “by Tuesday, they are miserable, they’re pretty beaten down. But by the end of the week, they’re like, ‘I could do another week,’” he says.

Their confidence grows as they recognize that, while they may not have taken college courses, their military experience is invaluable. “It’s just a matter of convincing these guys that what they are already doing is what we are looking for. We have guys that say, ‘I don’t know if I can succeed in an engineering program,’ but then in the field, they are repairing helicopters. And I’m like, ‘Oh no, you can do this stuff!’ They just need to understand the background of why that helicopter that they are building works.”

Olivier agrees. “The enlisted veteran has a leg up because they’ve already done this before. They are just translating it from either fixing a radio or messing around with the components of a bomb to understanding Newton’s laws. That’s a thing of beauty, when you see that.”

Fostering a virtuous cycle

While just seeing themselves succeed at MIT-WSP helps instill confidence among scholars, meeting veterans who have made the leap into academia has a multiplier effect. To that end, the WSP organization provides each academic boot camp with alumni, called fellows, to teach college success workshops, provide support, and share their experiences in higher education.

“When I was at boot camp, we had two WSP fellows who were at Columbia, one at Princeton, and one who just got accepted to Harvard,” Cole recalls. “Just seeing people existing at these institutions made me realize, this is a thing that is doable.” The following summer, he became a fellow as well.

Former Marine Corps communications operator Aaron Kahler, who attended MIT-WSP in 2024, particularly recalls meeting a veteran PhD student while the group toured the neuroscience facility. “It was really cool seeing instances of successful vets doing their thing at MIT,” he says. “There were a lot more than we thought.”

Over the years, McDonald has made an effort to recruit more MIT veterans to staff the program. One of them is Andrea Henshall, a retired major in the Air Force and a PhD student in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. After joining the Ask Me Anything panel a few years ago, she’s become increasingly involved, presenting lectures, mentoring participants, offering tours of the motion capture lab where she conducts experiments, and informally mentoring scholars.

“It’s so inspiring to hear so many students at the end of the week say, ‘I never considered a place like MIT until the boot camp, or until somebody told me, hey, you can be here, too.’ Or they see examples of enlisted veterans, like Justin, who’ve transitioned to a place like MIT and shown that it’s possible,” says Henshall.

At the conclusion of MIT-WSP, scholars receive a tangible reminder of what’s possible: a challenge coin designed by Olivier and McDonald. “In the military, the challenge coin usually has the emblem of the unit and symbolizes the ethos of the unit,” Olivier explains. On one side of the MIT-WSP coin are Newton’s laws of motion, superimposed over the WSP logo. MIT's “mens et manus” (“mind and hand”) motto appears on the other side, beneath an image of the Great Dome inscribed with the scholar’s name.

“As you go into Killian Court you see all the names of Pasteur, Newton, et cetera, but Building 10 doesn’t have a name on it,” he says. “So we say, ‘earn your space there on these buildings. Do something significant that will impact the human experience.’ And that’s what we think each one of these guys and gals can do.”

Kahler keeps the coin displayed on his desk at MIT, where he’s now a first-year student, for inspiration. “I don’t think I would be here if it weren’t for the Warrior-Scholar Project,” he says.