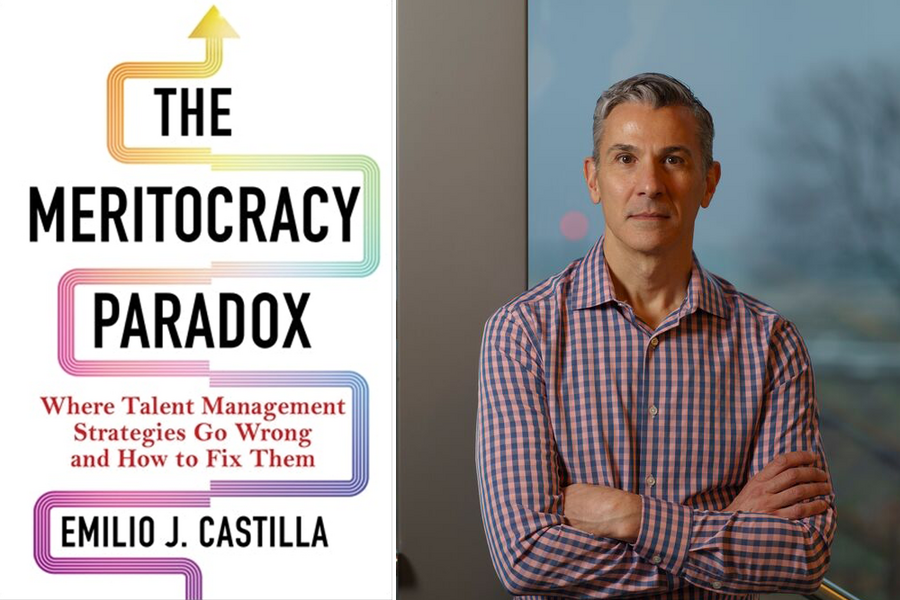

Can an organization ever be truly meritocratic? That’s a question Emilio J. Castilla, the NTU Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management, explores in his new book, “The Meritocracy Paradox: Where Talent Management Strategies Go Wrong and How to Fix Them” (Columbia University Press, 2025). Castilla, who is co-director of MIT’s Institute for Work and Employment Research (IWER), researches how talent is managed inside organizations and why — even with the best intentions — workplace practices often fail to deliver fairness and effectiveness.

Castilla’s book brings together decades of research to explain why organizations struggle to achieve meritocracy in practice — and what leaders can do to build fairer, more effective, and higher-performing workplaces. In the following Q&A, he unpacks how bias can unintentionally seep into hiring, evaluation, promotion, and reward systems, and offers concrete strategies to counteract these dynamics and design processes that recognize and support merit.

Q: One central argument of your book is that true meritocracy is not easy for organizations to achieve in practice. Why is that?

A. A large body of research has found that bias and unfairness can creep into the workplace, affecting talent management processes such as who gets interviewed for jobs, who gets hired, what kind of performance evaluations employees receive, and how employees are rewarded. So it’s not easy for an organization to be truly meritocratic.

In fact, research I conducted with Stephen Benard found that, ironically, emphasizing that an organization is a meritocracy may lead decision-makers to behave in more biased ways. Specifically, in our study, we found that when participants were told they were making decisions for an organization that emphasized meritocracy, they were more likely to recommend higher bonuses for male employees than for their equally-performing female peers, compared to when meritocracy wasn’t emphasized. We called this phenomenon the “paradox of meritocracy,” and it may stem from managers paying less attention to monitoring their own biases when they are assured the organization is fair.

A study I conducted with Aruna Ranganathan PhD ’14 further showed that managers’ understanding of what constitutes “merit” varies widely — even within the same organization. There is no universally agreed-upon definition, and our research found that managers often apply the concept of merit in ways that reflect their own experiences as employees. This variability can lead to inconsistent, and sometimes inequitable, outcomes.

Q. What are some of the things organizations can do to make their talent management practices more meritocratic?

A. The encouraging news is that making your organization’s talent management processes fairer and more meritocratic doesn’t have to be complex or expensive. It does, however, require buy-in from top management. The key factors, my research in organizations has shown, are organizational transparency and accountability.

To improve organizational transparency, you need to be very explicit and open about the criteria and procedures you use in talent management processes such as hiring, evaluation, promotion, and reward decisions. That’s because research has shown that having clear and specific merit-based criteria and well-defined processes can help reduce biases.

On the accountability side, you need to have at least one person responsible for monitoring the organization’s talent management processes and outcomes to ensure fairness and effectiveness. In practice, companies often give this responsibility to a group from different parts of the organization. Research has shown that knowing that your decisions will be reviewed by others causes managers to think carefully about their decisions — something that can reduce the impact of unconscious biases in the workplace.

Q. How realistic is it to think that organizations can ever be true meritocracies — and why do you nonetheless believe meritocracy is worth striving for?

A. It’s true that organizations are unlikely to ever be perfectly meritocratic. Still, striving for meritocracy and fairness in your talent management strategies is beneficial, and you should be aware of the pitfalls. Employers that hire, reward, and advance the most talented and hard-working employees, regardless of their demographic background, are likely to benefit in the long run. That’s the promise and enduring appeal of meritocracy.

Many in the United States may not realize that one of the world’s earliest formal meritocracies emerged in China during the Han and Qin dynasties more than 2,000 years ago. As early as 200 B.C.E., the Chinese empire began developing a system of civil service exams in order to identify and appoint competent and talented officials to help administer government operations throughout the empire.

Those Chinese emperors were on to something. Once an organization reaches a certain size, leaders won’t achieve the most effective performance if they make talent management decisions based on non-meritocratic factors such as nepotism, aristocracy/social class, corruption, or friendship. When it comes to choosing a guiding principle for people management decisions within an organization, meritocracy beats a lot of the alternatives.