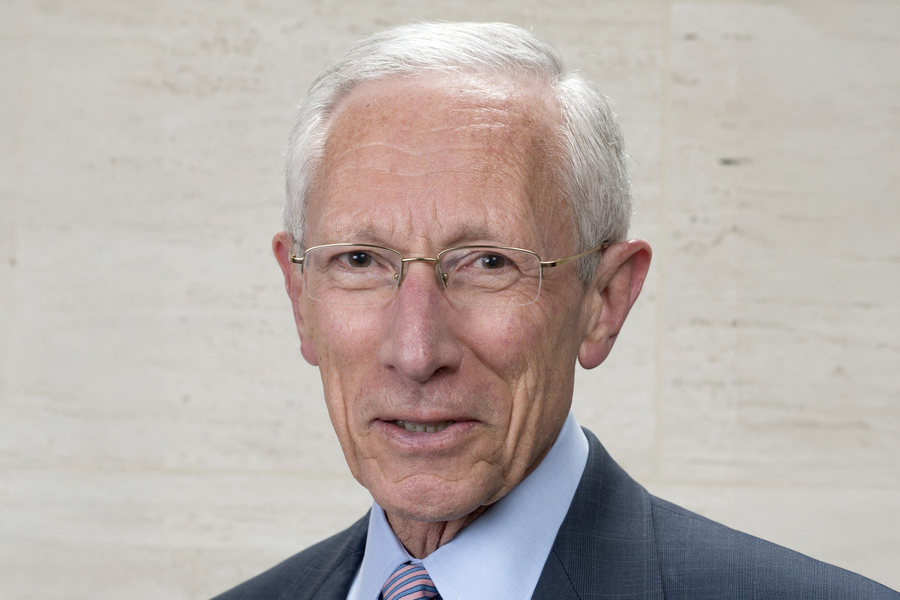

Stanley Fischer PhD ’69, MIT professor emeritus of economics and a towering figure in both academic macroeconomics and global economic policymaking, passed away on May 31. He was 81. Fischer was a foundational scholar as well as a wise mentor and a central force in shaping the macroeconomic tradition of MIT’s Department of Economics that continues today.

“Together with Rudi Dornbusch and later Olivier Blanchard, Stan was one of the intellectual engines that powered MIT macroeconomics in the 1970s and beyond,” says Ricardo Caballero PhD ’88, one of Fischer’s advisees and now the Ford International Professor of Economics at MIT. “He was quietly brilliant, never flashy, and always razor-sharp. His students learned not just from his lectures or his groundbreaking work on New Keynesian models and rational expectations, but from the clarity of his mind and the gentleness of his wit. Nearly 40 years later, I can still hear him saying: ‘Isn’t it easier to do it right the first time than to explain why you didn’t?’ That line has stayed with me ever since. A simple comment from Stan during a seminar — often offered with a disarming smile — could puncture a weak argument or crystallize a central insight. He taught generations of macroeconomists to prize discipline, clarity, and policy relevance.”

Olivier Blanchard PhD ’77, the Robert M. Solow Professor of Economics Emeritus at MIT and another advisee, explains that Fischer “was one of the most popular teachers, and one of the most popular thesis advisers. We flocked to his office, and I suspect that the only time for research he had was during the night. What we admired most were his technical skills — he knew how to use stochastic calculus — and his ability to take on big questions and simplify them to the point where the answer, ex post, looked obvious. When Rudi Dornbusch joined him in 1975, macro and international quickly became the most exciting fields at MIT.” Within a decade of his joining the MIT faculty, “Stan had acquired near-guru status.”

Fischer built bridges between economic theory and the practice of economic policy. He served as chief economist of the World Bank (1988-90), first deputy managing director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 1994-2001), governor of the Bank of Israel (2005-13), and vice chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve (2014-17). These leadership roles gave him a rare platform to implement ideas he helped develop in the classroom and he was widely praised for his successes at averting financial crises across several decades and continents. Yet even as he moved through the highest circles of global policymaking, he remained a teacher at heart — accessible, thoughtful, and generous with his time.

At MIT, Fischer is best remembered for inspiring generations of graduate students who moved between academics and policy just as he did. Over the course of two decades before he began his active policy role, he was primary adviser for 49 PhD students, secondary adviser to another 23, and a celebrated teacher for many more.

Many of his students became important macroeconomic policymakers, including Ben Bernanke PhD ’79; Mario Draghi PhD ’77; Ilan Goldfajn PhD ’95; Philip Lowe PhD ’91; and Kazuo Ueda PhD ’80, who chaired the Federal Reserve Board, the European Central Bank, the Banco Central do Brazil, the Reserve Bank of Australia, and the Bank of Japan. Students Gregory Mankiw PhD ’84 and Christina Romer PhD ’85 chaired the Council of Economic Advisors; Maurice Obstfeld PhD ’79 and Kenneth Rogoff PhD ’80 were chief economist at the International Monetary Fund; and Frederic Mishkin PhD ’76 was a governor of the Federal Reserve. Another of his students, former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers ’75, explains that “no one had more cumulative influence on the macroeconomic policymakers of the last generation than Stanley Fischer … We all were shaped by his clarity of thought, intellectual balance, personal decency, and quality of character. In a broader sense, everyone who was involved in the macro policy enterprise was Stan Fischer’s disciple. People all over the world who never knew his name lived better, more secure, lives because of all that he did through his teaching, writing, and service.”

Fischer grew up in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), living behind the general store his family ran before moving to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) at the age of 13. Inspired by the quality of writing in John Maynard Keynes’ “The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money,” he applied for and won a scholarship to study at the London School of Economics. He moved to MIT for his graduate studies, where his dissertation was supervised by Franklin M. Fisher. After several years on the University of Chicago faculty, he returned to MIT in 1973, where he stayed for the remainder of his academic career. He held the Elizabeth and James Killian Class of 1926 professorship from 1992 to 1995, serving as department chair in 1993–94, before being called away to the IMF.

Fischer’s intellectual journey from MIT to Chicago and back culminated in his most influential academic work. Ivan Werning, the Robert M. Solow Professor of Economics at MIT notes, “his research was pathbreaking and paved the way to the modern approach to macroeconomics. By merging nominal rigidities associated with MIT’s Keynesian tradition with rational expectations emanating from the Chicago school, his 1977 paper on ‘Long-Term Contracts, Rational Expectations, and the Optimal Money Supply Rule’ showed how the non-neutrality of money did not require agent irrationality or confusion.” The dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models now used at every central bank to evaluate monetary policy options are direct descendants of Fischer’s thinking.

Fischer’s influence goes beyond what has become known as New Keynesian Economics. Werning continues, “Fischer’s research combined theoretical insights to very applied questions. His textbook with Blanchard was instrumental to an entire generation of macroeconomists, showing macroeconomics as a rich and evolving field, ripe with tools and great questions to study. Along with Bob Solow, Rudi Dornbusch, and others, Fischer had a huge impact within the MIT economics department and helped build its day-to-day culture, with an inquisitive, open-minded, and friendly atmosphere.”

Macroeconomics — and MIT — owe him a profound debt.

Fischer is survived by his three sons, Michael, David, and Jonathan, and nine grandchildren.