MIT’s Initiative for New Manufacturing, announced today by President Sally A. Kornbluth, is the latest installment in a grand tradition: Since its founding, MIT has worked overtime to expand U.S. manufacturing, creating jobs and economic growth.

Indeed, one of the strongest through lines in MIT history is its commitment to U.S. manufacturing, which the Institute has pursued in economic good times and lean times, during wartime and in peacetime, and across scores of industries. MIT was founded in 1861 partly to improve U.S. industrial output, and has long devised special programs to bolster it — including multiple projects in recent decades aimed at renewing U.S. manufacturing.

“We want to deliberately design high-quality human-centered manufacturing jobs that bring new life to communities across the country,” Kornbluth wrote in a letter to the Institute community this morning, announcing the Initiative for New Manufacturing. She added: “I’m convinced that there is no more important work we can do to meet the moment and serve the nation now.”

“Embedded in MIT’s core ethos”

On one level, manufacturing is in MIT’s essential DNA. The Institute’s research and education has advanced industries from construction and transportation, to defense, electronics, biosciences, chemical engineering, and more. MIT contributions to management and logistics have also helped manufacturing firms thrive.

As Kornbluth noted in today’s letter, “Frankly, it’s not too much to say that the Institute was founded in 1861 to make manufacturing better.”

The historical record shows this, too. “There is no branch of practical industry, whether in the arts of construction, manufactures or agriculture, which is not capable of being better practiced, and even of being improved in its processes,” wrote MIT’s first president, William Barton Rogers, in a proposal for a new technical university, before MIT opened its doors.

“Manufacturing is embedded in MIT's core ethos,” says Christopher Love, a chemical engineering professor and one of the leads of the Initiative for New Manufacturing.

Beyond its everyday work, MIT has created many special projects to bolster manufacturing. In 1919, under the Institute’s third president, Richard Maclaurin, MIT developed the “Tech Plan,” engaging over 200 corporate sponsors, including AT&T and General Electric, to improve their businesses; period photos show MIT students examining a General Electric factory. (Similarly, today’s Initiative for New Manufacturing contains a “Factory Observatory” among its many facets, enabling Institute students to visit manufacturers.)

“Made in America”

For a few decades after World War II, the U.S. had an especially large global lead in manufacturing. The sector also accounted for roughly a quarter of U.S. GDP for much of the 1950s, compared to about 12 percent in recent years. To be sure, other U.S. industries naturally grew; additionally, global manufacturing increased. But the U.S. still had around 20 million manufacturing jobs in 1979, compared to about 12.8 million today. The 1980s saw concerted job loss in manufacturing, and many believed the U.S. was losing its edge in key industries, including automaking and consumer electronics.

In response, MIT formed a task force on the subject, the MIT Commission on Industrial Productivity — and this group project created a bestselling book.

“Made in America: Regaining the Productive Edge,” co-authored by Michael Dertouzos, Richard Lester, and Robert Solow, sold over 300,000 copies after its publication in 1989. The book closely examined U.S. manufacturing practices across eight core industries and found overly short growth horizons for firms, suboptimal technology transfer, a neglect of human resources, and more.

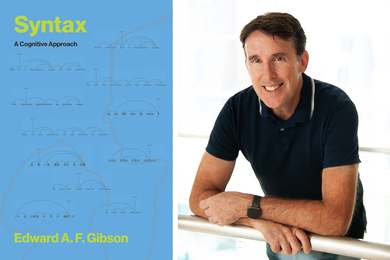

Solow was an apt co-author: The MIT economist produced breakthrough research in the 1950s and 1960s, based on U.S. economic data, showing that technical advances of multiple kinds were responsible for most economic growth — to a much greater extent than, say, population growth or capital expansion. “Total factor productivity,” as Solow called it, included technological innovation, education, and skill-related changes.

Solow’s work won him a Nobel Prize in 1987 and illuminated how important technology and education are to economic expansion: Growth is not largely about making more of the same stuff, but creating new things.

The 21st Century: PIE, The Engine, and INM

This century, manufacturing has had periods of growth, but heavy job losses in the first decade of the 2000s. That led to a flurry of new MIT manufacturing projects and research.

For one, an Institute task force on Production in the Innovation Economy (PIE), based on two years of empirical research, found considerable potential for U.S. advanced manufacturing, but also that the country needed to improve its capacity at turning innovations into deliverable products. These finding were detailed in the book “Making in America,” written by Institute Professor Suzanne Berger, a political scientist who has long studied the industrial economy.

MIT also participated in a government initiative, the Advanced Manufacturing Partnership, to help create high-tech economic hubs in parts of the U.S. that had suffered from de-industrialization, an effort that included developing new education initiatives for industrial workers.

And in 2016, MIT first announced a creative effort to spur manufacturing directly, in the form of The Engine, a startup accelerator, innovation hub, and venture fund located adjacent to campus in Cambridge. The Engine seeks to boost promising “tough tech” startups that need time to gain traction, and has invested in dozens of promising companies.

Additionally, MIT’s Work of the Future task force, a multi-year project issuing a final report in 2020, uncovered manufacturing insights while not being solely focused on them. The task fore found that automation will not wipe away colossal numbers of jobs — but that a key issue for the future is how technology can help workers to spur productivity, while not replacing them.

MIT continues to feature a variety of long-term programs and centers focused on manufacturing. The Initiative for New Manufacturing is an outgrowth of the Manufacturing@MIT working group; MIT’s Leaders for Global Operations (LGO) program offers a dual Engineering-MBA degree with a strong focus on manufacturing; the Department of Mechanical Engineering offers an advanced manufacturing concentration; and the Industrial Liason Program develops corporate partnerships with MIT.

All told, as Kornbluth wrote in today’s letter, “Manufacturing has been a throughline in MIT’s research and education … and it’s been an essential part of our service to the nation.”