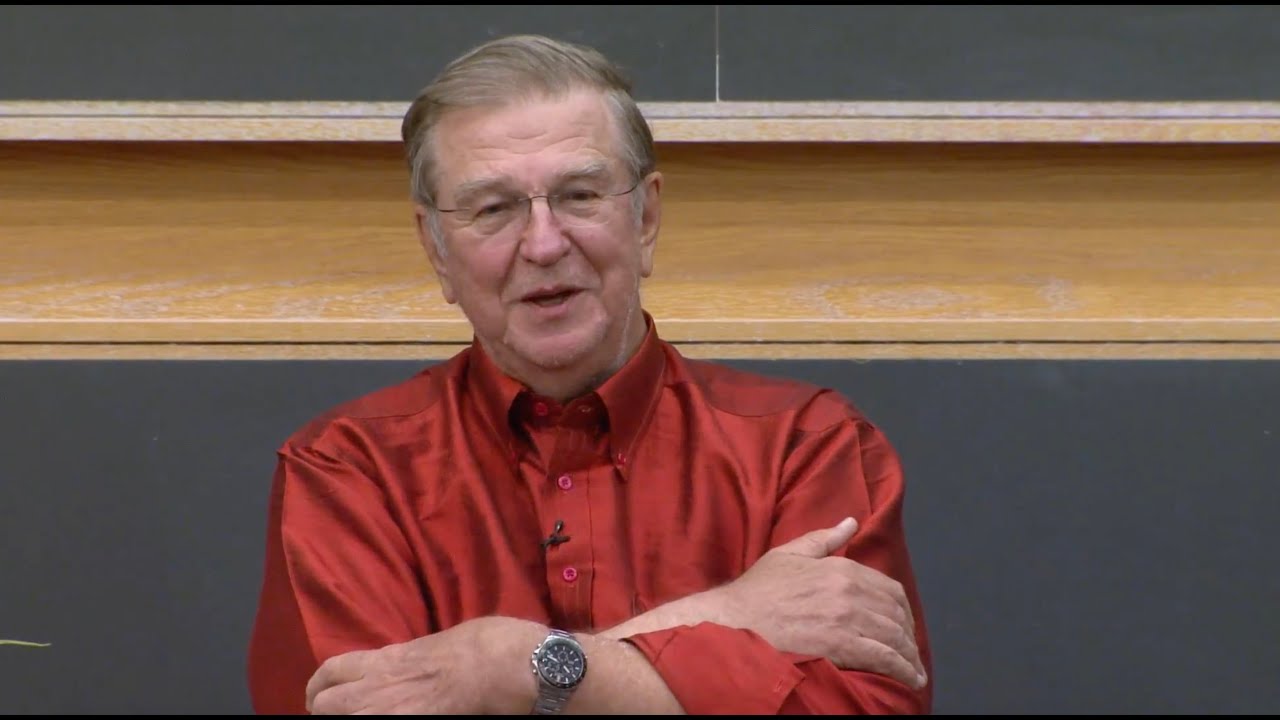

Longtime MIT Professor Anthony “Tony” Sinskey ScD ’67, who was also the co-founder and faculty director of the Center for Biomedical Innovation (CBI), passed away on Feb. 12 at his home in New Hampshire. He was 84.

Deeply engaged with MIT, Sinskey left his mark on the Institute as much through the relationships he built as the research he conducted. Colleagues say that throughout his decades on the faculty, Sinskey’s door was always open.

“He was incredibly generous in so many ways,” says Graham Walker, an American Cancer Society Professor at MIT. “He was so willing to support people, and he did it out of sheer love and commitment. If you could just watch Tony in action, there was so much that was charming about the way he lived. I’ve said for years that after they made Tony, they broke the mold. He was truly one of a kind.”

Sinskey’s lab at MIT explored methods for metabolic engineering and the production of biomolecules. Over the course of his research career, he published more than 350 papers in leading peer-reviewed journals for biology, metabolic engineering, and biopolymer engineering, and filed more than 50 patents. Well-known in the biopharmaceutical industry, Sinskey contributed to the founding of multiple companies, including Metabolix, Tepha, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, and Genzyme Corporation. Sinskey’s work with CBI also led to impactful research papers, manufacturing initiatives, and educational content since its founding in 2005.

Across all of his work, Sinskey built a reputation as a supportive, collaborative, and highly entertaining friend who seemed to have a story for everything.

“Tony would always ask for my opinions — what did I think?” says Barbara Imperiali, MIT’s Class of 1922 Professor of Biology and Chemistry, who first met Sinskey as a graduate student. “Even though I was younger, he viewed me as an equal. It was exciting to be able to share my academic journey with him. Even later, he was continually opening doors for me, mentoring, connecting. He felt it was his job to get people into a room together to make new connections.”

Sinskey grew up in the small town of Collinsville, Illinois, and spent nights after school working on a farm. For his undergraduate degree, he attended the University of Illinois, where he got a job washing dishes at the dining hall. One day, as he recalled in a 2020 conversation, he complained to his advisor about the dishwashing job, so the advisor offered him a job washing equipment in his microbiology lab.

In a development that would repeat itself throughout Sinskey’s career, he befriended the researchers in the lab and started learning about their work. Soon he was showing up on weekends and helping out. The experience inspired Sinskey to go to graduate school, and he only applied to one place.

Sinskey earned his ScD from MIT in nutrition and food science in 1967. He joined MIT’s faculty a few years later and never left.

“He loved MIT and its excellence in research and education, which were incredibly important to him,” Walker says. “I don’t know of another institution this interdisciplinary — there’s barely a speed bump between departments — so you can collaborate with anybody. He loved that. He also loved the spirit of entrepreneurship, which he thrived on. If you heard somebody wanted to get a project done, you could run around, get 10 people, and put it together. He just loved doing stuff like that.”

Working across departments would become a signature of Sinskey’s research. His original office was on the first floor of MIT’s Building 56, right next to the parking lot, so he’d leave his door open in the mornings and afternoons and colleagues would stop in and chat.

“One of my favorite things to do was to drop in on Tony when I saw that his office door was open,” says Chris Kaiser, MIT’s Amgen Professor of Biology. “We had a whole range of things we liked to catch up on, but they always included his perspectives looking back on his long history at MIT. It also always included hopes for the future, including tracking trajectories of MIT students, whom he doted on.”

Long before the internet, colleagues describe Sinskey as a kind of internet unto himself, constantly leveraging his vast web of relationships to make connections and stay on top of the latest science news.

“He was an incredibly gracious person — and he knew everyone,” Imperiali says. “It was as if his Rolodex had no end. You would sit there and he would say, ‘Call this person.’ or ‘Call that person.’ And ‘Did you read this new article?’ He had a wonderful view of science and collaboration, and he always made that a cornerstone of what he did. Whenever I’d see his door open, I’d grab a cup of tea and just sit there and talk to him.”

When the first recombinant DNA molecules were produced in the 1970s, it became a hot area of research. Sinskey wanted to learn more about recombinant DNA, so he hosted a large symposium on the topic at MIT that brought in experts from around the world.

“He got his name associated with recombinant DNA for years because of that,” Walker recalls. “People started seeing him as Mr. Recombinant DNA. That kind of thing happened all the time with Tony.”

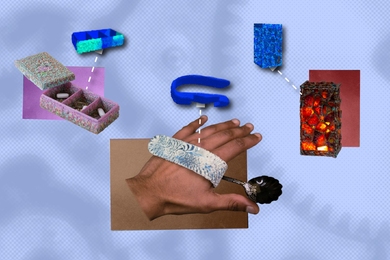

Sinskey’s research contributions extended beyond recombinant DNA into other microbial techniques to produce amino acids and biodegradable plastics. He co-founded CBI in 2005 to improve global health through the development and dispersion of biomedical innovations. The center adopted Sinskey’s collaborative approach in order to accelerate innovation in biotechnology and biomedical research, bringing together experts from across MIT’s schools.

“Tony was at the forefront of advancing cell culture engineering principles so that making biomedicines could become a reality. He knew early on that biomanufacturing was an important step on the critical path from discovering a drug to delivering it to a patient,” says Stacy Springs, the executive director of CBI. “Tony was not only my boss and mentor, but one of my closest friends. He was always working to help everyone reach their potential, whether that was a colleague, a former or current researcher, or a student. He had a gentle way of encouraging you to do your best.”

“MIT is one of the greatest places to be because you can do anything you want here as long as it’s not a crime,” Sinskey joked in 2020. “You can do science, you can teach, you can interact with people — and the faculty at MIT are spectacular to interact with.”

Sinskey shared his affection for MIT with his family. His wife, the late ChoKyun Rha ’62, SM ’64, SM ’66, ScD ’67, was a professor at MIT for more than four decades and the first woman of Asian descent to receive tenure at MIT. His two sons also attended MIT — Tong-ik Lee Sinskey ’79, SM ’80 and Taeminn Song MBA ’95, who is the director of strategy and strategic initiatives for MIT Information Systems and Technology (IS&T).

Song recalls: “He was driven by same goal my mother had: to advance knowledge in science and technology by exploring new ideas and pushing everyone around them to be better.”

Around 10 years ago, Sinskey began teaching a class with Walker, Course 7.21/7.62 (Microbial Physiology). Walker says their approach was to treat the students as equals and learn as much from them as they taught. The lessons extended beyond the inner workings of microbes to what it takes to be a good scientist and how to be creative. Sinskey and Rha even started inviting the class over to their home for Thanksgiving dinner each year.

“At some point, we realized the class was turning into a close community,” Walker says. “Tony had this endless supply of stories. It didn’t seem like there was a topic in biology that Tony didn’t have a story about either starting a company or working with somebody who started a company.”

Over the last few years, Walker wasn’t sure they were going to continue teaching the class, but Sinskey remarked it was one of the things that gave his life meaning after his wife’s passing in 2021. That decided it.

After finishing up this past semester with a class-wide lunch at Legal Sea Foods, Sinskey and Walker agreed it was one of the best semesters they’d ever taught.

In addition to his two sons, Sinskey is survived by his daughter-in-law Hyunmee Elaine Song, five grandchildren, and two great grandsons. He has two brothers, Terry Sinskey (deceased in 1975) and Timothy Sinskey, and a sister, Christine Sinskey Braudis.

Gifts in Sinskey’s memory can be made to the ChoKyun Rha (1962) and Anthony J Sinskey (1967) Fund.