Through compelling personal stories and dramatic research evidence, speakers at the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory’s recent “Early Life Stress and Mental Health” symposium showed that people are making progress in helping children survive toxic stress through science and activism.

Whether in the lab, the clinic, or the community, the key is to ask deep questions and to invest the time and energy to grapple with the heartbreaking, multifaceted complexity underlying how adverse experiences such as neglect or abuse can affect the health of children. It can lead to strikingly higher likelihoods of mental illness and reduced lifespan.

“We do everything that we can to help primarily low-income children and parents,” JPB Foundation President Barbara Picower said at the May 9 event. The foundation supports many of the event’s speakers and collaborated with the Institute to organize the daylong conference, a biennial event at MIT since 2012. “Toxic stress is something that is so damaging to children, the results of it occur through the lifetime.”

MIT Provost Martin Schmidt added: “The topic of this symposium could not be more important for our society, morally or practically.”

Speakers reinforced Picower and Schmidt’s introduction with an abundance of data. New Jersey children traumatized by Superstorm Sandy in 2012, even if their homes suffered only minor damage, were five times more likely to be depressed and to report feelings of nervousness and fear years later, reported Patricia Findley, an associate professor of social work at Rutgers University.

Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician and founder of the Center for Youth Wellness in San Francisco, presented data from a major review study and other sources showing that experiencing four or more adverse childhood events (ACEs) is associated with an 5.6-fold risk of drug abuse, an 11 times increased risk of Alzheimer’s and a 30-times greater risk of suicide. In all, ACEs can reduce longevity by decades.

Digging deeper

Though such associations are well known, Burke Harris said, few pediatricians screen for ACEs. And failing to discover those underlying problems can lead to misguided treatment.

Many behavioral problems associated with toxic stress, for example, come across as ADHD but are caused by the chronically elevated inflammatory, or human “fight-or-flight,” response that originally evolved for surviving dangers like encountering a bear in the forest, but that stressed children live with constantly, she said. “The problem is what happens when that bear comes home every night,” she said.

Without screening for that underlying stress, doctors often prescribe ritalin, a stimulant. But in a child enduring a chronic stress response, that medication likely won’t do much good. Instead, if screening reveals ACEs, Burke Harris works to mitigate the stresses and prescribes guanfacine, which calms the nervous system and reduces blood pressure.

Keynote speaker Geoffrey Canada, president of the Harlem Children’s Zone, told a similar anecdote about the need to dig deeper. Years ago, a social worker in HCZ’s after-school program alerted him to a child who began to display bizarre behaviors such as talking to himself. Rather than just sending the child to a doctor, Canada sent the social worker to visit the home. The visit revealed that the tiny apartment was infested with rats and the child’s mother, who needed to work, had tasked the boy with guarding his younger sisters from being bitten at night. The boy’s problem was not mental illness so much as a profound lack of sleep.

“If you aren’t willing to take the time to actually figure out what’s happened to a child you might treat the child for something that isn’t really causing that kid to be sick,” Canada said. “You have to really take the time to understand.”

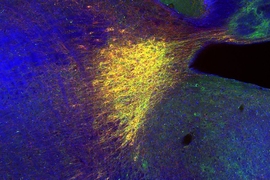

The desire to dig deeper brought Ravi Raju to the lab of Picower Institute Director Li-Huei Tsai, where he is a Picower Clinical Fellow. After observing stark health and income disparities among Boston children during his pediatrics residency at local hospitals, Raju decided to do fundamental research on how deprivation amid poverty affects the brain. Using an experimental protocol in which mice are deprived of nesting materials, an important component of pup rearing, Raju has shown that baby mice appear to adapt via specific changes in gene expression. Those that do remain resilient. Those that don’t become very anxious. Studying those genes and the molecular pathways they affect when expressed is revealing potential therapeutic targets for mitigating toxic stress, he said.

In India, MIT economics professor Frank Schilbach is testing interventions to help alleviate poverty cycles. His research shows how intricately problems in households are intertwined. Among poor workers, for instance, back-breaking labor leads to debilitating pain. With poor health care, many laborers start drinking alcohol to feel better. Difficulties at home, including for their children, often follow. Amid this cycle, he’s found, is poor sleep, an often underappreciated factor where interventions could help.

Babies show amazing acumen in what they pick up from the adults around them, said MIT cognitive scientist Laura Schulz, professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences. She described her research demonstrating that babies will match the degree of effort they observe a grown-up making when trying to figure a task out. Another set of experiments shows how adult can constrain a child’s thinking. If an adult specifically demonstrates only one feature of a multi-featured toy, for example, a child won’t explore the toy to discover any of its other features.

Speaking up

As important as speakers said it is for scientists, physicians, and social workers to engage in deep, energetic efforts to understand the underlying cognitive abilities and vulnerabilities of children, several other speakers emphasized how crucial it is for afflicted communities and people to insist on being heard.

Mona Hanna-Attisha, associate professor of pediatrics at Michigan State University, spoke at the symposium about the extensive research she did to prove the horrible extent of lead poisoning among children in Flint, Michigan, after the city infamously switched its water supply a few years ago. Community complaints about foul water were dismissed. Research documented how wrong that was.

“They were told the water was fine,” she said. “Science is not meant to live in publications and journals and ivory towers. The purpose of science is to benefit our communities.”

After she revealed the problem, social and health services have increased in the city, but now the fight continues to sustain funding for those restorative efforts, said Hanna-Attisha, who won an MIT Media Lab “Disobedience Award.”

Though pollution is an abundant problem, other speakers described how the environment can protect against toxic stress. Marc Berman, assistant professor of psychology at the University of Chicago, described his findings that exposure to trees and natural scenes may improve cognition. Meanwhile Jonathan F.P. Rose, a prominent builder of progressive mixed-income communities, described how his developments incorporate vegetation, as well as medical and social services rather than just providing housing.

But several speakers made it clear that they’ve had to advocate and sometimes fight systems to mitigate toxic stress in their communities. On a panel with Frank Farrow of the Center for the Study of Social Policy and Boston University pediatrician Renee Boynton-Jarrett, local parents Lisa Melara and Gihan Suliman spoke of their tireless volunteer work to help parents find supportive community resources and understand their rights. Later in the day, journalist and filmmaker Jose Antonio Vargas, CEO of Define American, described his work in creating communities among undocumented immigrants such as himself, to help fight hatred by ensuring their stories are told.

Several speakers pulled few punches about how ongoing problems of poverty, violence, substance abuse and racism continue to produce toxic stress in children, even as they also reported their strides in research and community action to mitigate its effects.

Harvard University professor and child health expert Jack Shonkoff noted that for all the advances in research and community services, their impact has not been nearly enough.

Shonkoff put it in terms of the “Stockdale Paradox,” named for a former U.S. prisoner of war in Vietnam. To survive, goes the paradox, one must never lose hope of ultimately prevailing, even while remaining brutally honest about how dire the current situation really is.