A miniature satellite called ASTERIA (Arcsecond Space Telescope Enabling Research in Astrophysics) has measured the transit of a previously-discovered super-Earth exoplanet, 55 Cancri e. This finding shows that miniature satellites, like ASTERIA, are capable of making of sensitive detections of exoplanets via the transit method.

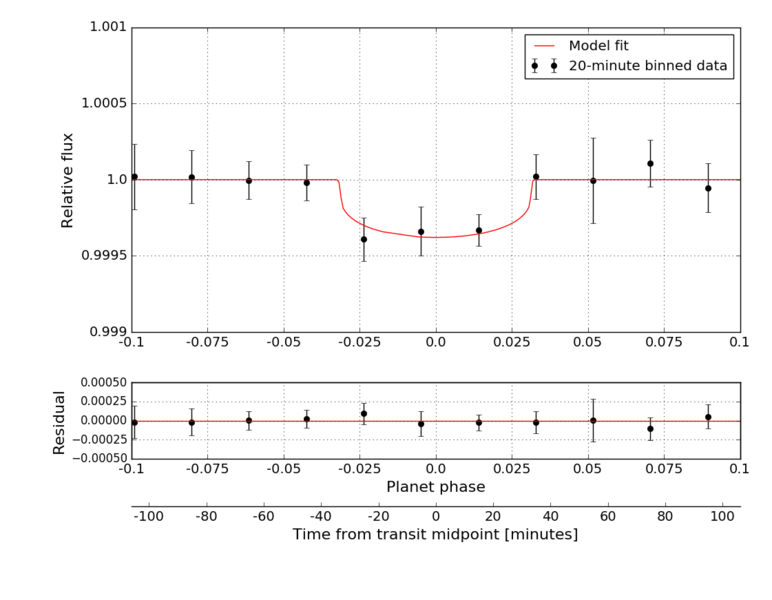

While observing 55 Cancri e, which is known to transit, ASTERIA measured a miniscule change in brightness, about 0.04 percent, when the super-Earth crossed in front of its star. This transit measurement is the first of its kind for CubeSats (the class of satellites to which ASTERIA belongs) which are about the size of a briefcase and hitch a ride to space as secondary payloads on rockets used for larger spacecraft.

The ASTERIA team presented updates and lessons learned about the mission at the Small Satellite Conference in Logan, Utah, last week.

The ASTERIA project is a collaboration between MIT and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, funded through JPL's Phaeton Program. The project started in 2010 as an undergraduate class project in 16.83/12.43 (Space Systems Engineering), involving a technology demonstration of astrophysical measurements using a Cubesat, with a primary goal of training early-career engineers.

The ASTERIA mission was designed to demonstrate key technologies, including very stable pointing and thermal control for making extremely precise measurements of stellar brightness in a tiny satellite. Its principal investigator is Sara Seager, the Class of 1941 Professor Chair in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences with appointments in the departments of Physics and Aeronautics and Astronautics. Earlier this year, ASTERIA achieved pointing stability of 0.5 arcseconds and thermal stability of 0.01 degrees Celsius. These technologies are important for precision photometry, i.e., the measurement of stellar brightness over time.

Precision photometry, in turn, provides a way to study stellar activity, transiting exoplanets, and other astrophysical phenomena. Several MIT alumni have been involved in ASTERIA's development from the beginning including Matthew W. Smith PhD '14, Christopher Pong ScD '14, Alessandra Babuscia PhD '12, and Mary Knapp PhD '18. Brice-Olivier Demory, a professor at the University of Bern and a former EAPS postdoc who is also a member of the ASTERIA science team, performed the data reduction that revealed the transit.

ASTERIA's success demonstrates that CubeSats can perform big science in a small package. This finding has earned ASTERIA the honor of "Mission of the Year,” which was awarded at the SmallSat conference. The honor is presented annually to the mission that has demonstrated a significant improvement in the capability of small satellites, which weigh less than 150 kilograms. Eligible missions have launched, established communication, and acquired results from on-orbit after Jan, 1, 2017.

Now that ASTERIA has proven that it can measure exoplanet transits, it will continue observing two bright, nearby stars to search for previously unknown transiting exoplanets. Additional funding for ASTERIA operations was provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation