MIT researchers have devised a way to measure dopamine in the brain much more precisely than previously possible, which should allow scientists to gain insight into dopamine’s roles in learning, memory, and emotion.

Dopamine is one of the many neurotransmitters that neurons in the brain use to communicate with each other. Previous systems for measuring these neurotransmitters have been limited in how long they provide accurate readings and how much of the brain they can cover. The new MIT device, an array of tiny carbon electrodes, overcomes both of those obstacles.

“Nobody has really measured neurotransmitter behavior at this spatial scale and timescale. Having a tool like this will allow us to explore potentially any neurotransmitter-related disease,” says Michael Cima, the David H. Koch Professor of Engineering in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, and the senior author of the study.

Furthermore, because the array is so tiny, it has the potential to eventually be adapted for use in humans, to monitor whether therapies aimed at boosting dopamine levels are succeeding. Many human brain disorders, most notably Parkinson’s disease, are linked to dysregulation of dopamine.

“Right now deep brain stimulation is being used to treat Parkinson’s disease, and we assume that that stimulation is somehow resupplying the brain with dopamine, but no one’s really measured that,” says Helen Schwerdt, a Koch Institute postdoc and the lead author of the paper, which appears in the journal Lab on a Chip.

Studying the striatum

For this project, Cima’s lab teamed up with David H. Koch Institute Professor Robert Langer, who has a long history of drug delivery research, and Institute Professor Ann Graybiel, who has been studying dopamine’s role in the brain for decades with a particular focus on a brain region called the striatum. Dopamine-producing cells within the striatum are critical for habit formation and reward-reinforced learning.

Until now, neuroscientists have used carbon electrodes with a shaft diameter of about 100 microns to measure dopamine in the brain. However, these can only be used reliably for about a day because they produce scar tissue that interferes with the electrodes’ ability to interact with dopamine, and other types of interfering films can also form on the electrode surface over time. Furthermore, there is only about a 50 percent chance that a single electrode will end up in a spot where there is any measurable dopamine, Schwerdt says.

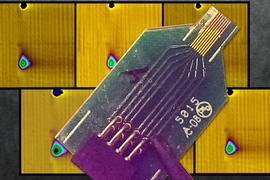

The MIT team designed electrodes that are only 10 microns in diameter and combined them into arrays of eight electrodes. These delicate electrodes are then wrapped in a rigid polymer called PEG, which protects them and keeps them from deflecting as they enter the brain tissue. However, the PEG is dissolved during the insertion so it does not enter the brain.

These tiny electrodes measure dopamine in the same way that the larger versions do. The researchers apply an oscillating voltage through the electrodes, and when the voltage is at a certain point, any dopamine in the vicinity undergoes an electrochemical reaction that produces a measurable electric current. Using this technique, dopamine’s presence can be monitored at millisecond timescales.

Using these arrays, the researchers demonstrated that they could monitor dopamine levels in many parts of the striatum at once.

“What motivated us to pursue this high-density array was the fact that now we have a better chance to measure dopamine in the striatum, because now we have eight or 16 probes in the striatum, rather than just one,” Schwerdt says.

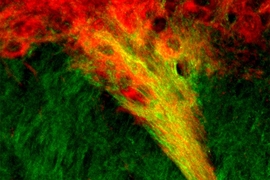

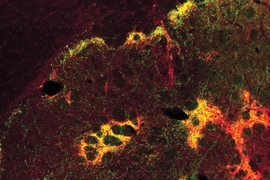

The researchers found that dopamine levels vary greatly across the striatum. This was not surprising, because they did not expect the entire region to be continuously bathed in dopamine, but this variation has been difficult to demonstrate because previous methods measured only one area at a time.

Pavel Takmakov, a staff fellow at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, says that the new approach is a dramatic improvement from the current method of using one electrode to sample just a tiny fraction of the brain.

"The microfabricated carbon-fiber arrays developed by the MIT team provide a significant leap forward in this technology, with demonstration of simultaneous sampling of dopamine at several brain sites,” says Takmakov, who was not involved in the research. "This provides an unprecedented opportunity to access cross-talk between different brain regions and to understand its role in healthy and diseased brain states.”

How learning happens

The researchers are now conducting tests to see how long these electrodes can continue giving a measurable signal, and so far the device has kept working for up to two months. With this kind of long-term sensing, scientists should be able to track dopamine changes over long periods of time, as habits are formed or new skills are learned.

“We and other people have struggled with getting good long-term readings,” says Graybiel, who is a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research. “We need to be able to find out what happens to dopamine in mouse models of brain disorders, for example, or what happens to dopamine when animals learn something.”

She also hopes to learn more about the roles of structures in the striatum known as striosomes. These clusters of cells, discovered by Graybiel many years ago, are distributed throughout the striatum. Recent work from her lab suggests that striosomes are involved in making decisions that induce anxiety.

This study is part of a larger collaboration between Cima’s and Graybiel’s labs that also includes efforts to develop injectable drug-delivery devices to treat brain disorders.

“What links all these studies together is we’re trying to find a way to chemically interface with the brain,” Schwerdt says. “If we can communicate chemically with the brain, it makes our treatment or our measurement a lot more focused and selective, and we can better understand what’s going on.”

Other authors of the paper are McGovern Institute research scientists Minjung Kim, Satoko Amemori, and Hideki Shimazu; McGovern Institute postdoc Daigo Homma; McGovern Institute technical associate Tomoko Yoshida; and undergraduates Harshita Yerramreddy and Ekin Karasan.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.