When Juan Jaramillo was young, he would ask his father endless questions about the world around him, particularly during the 12-hour road trips his family made between Mexico and Texas.

“I'd ask him so many questions and he had an answer for literally everything,” Jaramillo says.

Jaramillo, a chemical engineering major, has learned a great deal since then, but during his time at MIT, he has never lost the intense curiosity he had as a child. Whether he is conducting chemistry research or running Camp Kesem, an overnight camp for children whose parents have been affected by cancer, Jaramillo is always eager to learn more and to use his knowledge to help others.

Strong family ties

Jaramillo grew up in a small town in Mexico, and he was first exposed to science by his father, a chemistry and physics teacher. His father was working two jobs at the time, yet always made time to bring experiments home from his physics class.

“He'd grade his papers until really late at night,” Jaramillo recalls. “But he still had that inquisitiveness in him, and that was really positive in my development.”

When Jaramillo was 13, his parents moved the family to Houston, Texas, where he enrolled in school as an English as a Second Language (ESL) student. He recalls translating for his parents as they went through the process of buying a house, even though he was still learning English.

“I think I had to grow up a little bit faster because my parents couldn't hold my hand for so long,” he says. “I've had to grow due to the necessity of helping them out. I think that's been very meaningful for me.”

Jaramillo describes himself as a far-from-perfect student in high school, but during his junior year, a classmate encouraged him to apply for the Minority Introduction to Engineering and Science (MITES) summer program through the MIT Office of Engineering Outreach Programs. As a MITES student, Jaramillo spent six weeks at MIT completely immersed in science and engineering coursework, and he quickly realized that MIT was where we wanted to be for college.

“I learned that MIT is a place that gives you the resources, and if you want to use them, you'll make something very beautiful and positively productive,” he says. “So I applied and fortunately I got in early. It was a dream come true.”

Exploring chemistry through research

At MIT, Jaramillo was immediately attracted to chemistry, which he describes as the most magical scientific field.

“I think that chemistry is one of the most beautiful sciences because it's the one that interacts with your senses the most,” he explains.

However, Jaramillo decided that he would be able to help the greatest number of people in the most meaningful way by pursuing chemistry within the context of engineering.

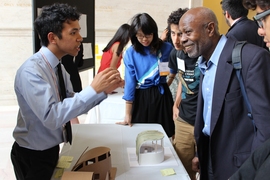

For two years, Jaramillo conducted crystals engineering research with Allan Myerson, professor of the practice of chemical engineering. Jaramillo worked on designing a system called Pharmacy on Demand. The system is roughly the size of a refrigerator, but it can synthesize raw chemicals into usable medications, which is especially needed in developing communities where it is not possible to ship medications.

“It definitely fueled my drive to positively affect people through engineering,” Jaramillo says of the experience

Near the end of his junior year, Jaramillo, who hopes to someday own a vineyard, jumped at the chance to work with Jean-François Hamel, a research engineer in the Department of Chemical Engineering, on fermentation research. According to Jaramillo, as climate change drives up temperatures, vineyards are growing grapes with a higher sugar content. More sugar means that the yeast added during the wine making process produces more ethanol, resulting in more alcoholic wine. Jaramillo and the team are addressing this problem by developing a new fermentation system that will lower the alcohol content of the wine. Jaramillo worked on the project full time this past winter break, and he has particularly enjoyed being involved in all stages of the research.

“This has been one of the most independent types of research that I've been able to have,” he says. “I've been able to be essentially what a grad student is and conducting my own research.”

Helping others, changing course

Beyond his research, Jaramillo has devoted much of his time at MIT to Camp Kesem. The one-week camp for children whose parents are dealing with cancer will celebrate its 10th anniversary this summer and now serves over 180 campers each summer, free of charge.

Jaramillo has been involved in various leadership roles within the organization and currently serves as the outreach and operations director. His goal is to help the children and their families as much as possible, by raising funds to run the camp, making sure the campers have an amazing experience, or providing support to the families throughout the year.

Jaramillo has worked particularly hard at improving Camp Kesem’s efforts to maintain close relationships with the families year-round, which have included inviting campers to MIT, sending counselors to visit families, and organizing several successful camp reunions.

During his first summer as a counselor, Jaramillo worked with the 6- to 8-year-old campers, and it was their boundless energy and enthusiasm, even in the face of adversity, that inspired him to do more. As Jaramillo became increasingly involved in Camp Kesem, he started to rethink his own path. Jaramillo recounts a moment of realization that came one morning this past summer, after he stayed up late to help a camper through an emotional time.

“I woke up really early to my alarm and I was pretty tired, yet all I wanted to do was get up, and wake everybody up, because I just didn't see it working any other way,” he says. “I had this intrinsic urgency to help these children get up and have the best time of their lives, and I realized that I never had that experience anywhere else.”

From that point on, Jaramillo knew that while he appreciates all the good that can be accomplished through engineering, he wanted to have a more personal and immediate impact on people’s lives.

“I decided that what I want to do is go into the medical field so I can continue to positively affect people,” he says.

Beyond MIT

For Jaramillo, who graduates this spring, medical school is a little way down the road. He has accepted a position at a biotechnology company called Lyndra, which is working on extending the delivery time for medications so a single dose lasts for several weeks. This innovation will help people who aren’t used to taking daily medication or lack regular access to medical professionals.

“It’s a really great pursuit. It's a really big market, and I think this is the best stepping stone into the medical field,” he says. “I think this will fuel my drive to go into helping people out just the way I wanted to.”

Jaramillo also hopes to provide financial support to his family and relieve some of the burden on his father, who has been working in construction since their family moved to Texas.

“Since I was really young, I was very much instilled with the idea that my family comes first,” he says. “I've had my goal since I came to the United States to help [my father] stop having these jobs, to take a rest and finally retire. I'm really excited that I'm in the process of going into industry, and I can now help him out.”

When Jaramillo was young his father urged him to read The Little Prince, which describes the adventures of a young prince as he travels to different planets. Jaramillo was 19 when he finally read the book, and when he did, he immediately saw himself in the prince, who is fascinated by everything he sees and everyone he meets. Jaramillo recalls one story where the prince meets a man counting stars. The prince is eager to learn about the stars, but the man has lost so much of his passion and enthusiasm over the years that he refuses to answer a single question. The book made Jaramillo realize that no matter where he is or what he is doing, he must always stay curious and excited about the world.

“Slowly you can turn your passions into something really negative. An obligation, almost, that's not necessarily positive for you,” he says. “I wanted to make sure everything that I did from that moment forward was geared toward making sure that I had this happiness in me, good-being effervescence. That I always stay positive.”