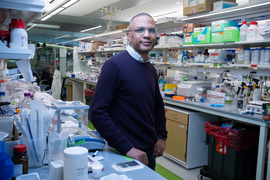

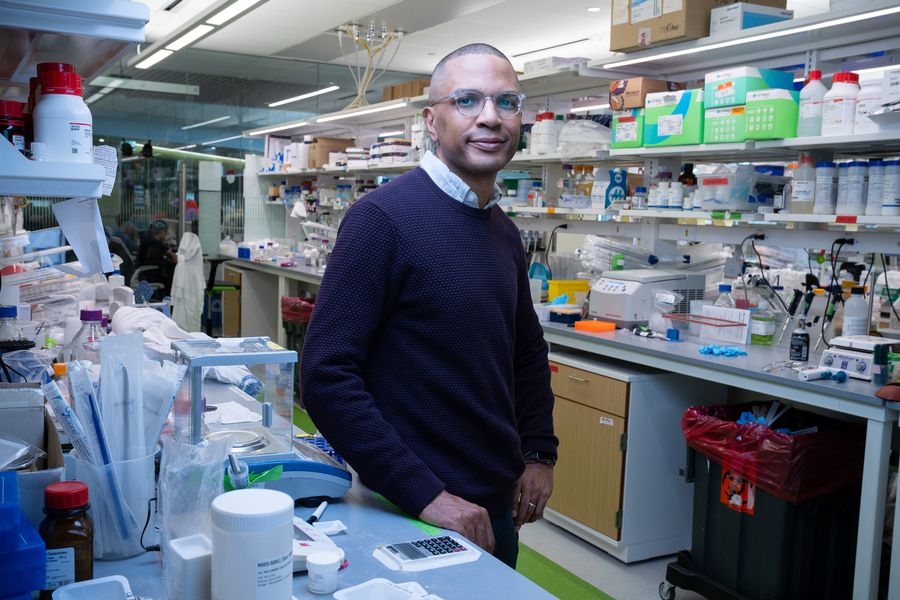

On his desk, Bryan Bryson ’07, PhD ’13 still has the notes he used for the talk he gave at MIT when he interviewed for a faculty position in biological engineering. On that sheet, he outlined the main question he wanted to address in his lab: How do immune cells kill bacteria?

Since starting his lab in 2018, Bryson has continued to pursue that question, which he sees as critical for finding new ways to target infectious diseases that have plagued humanity for centuries, especially tuberculosis. To make significant progress against TB, researchers need to understand how immune cells respond to the disease, he says.

“Here is a pathogen that has probably killed more people in human history than any other pathogen, so you want to learn how to kill it,” says Bryson, now an associate professor at MIT. “That has really been the core of our scientific mission since I started my lab. How does the immune system see this bacterium and how does the immune system kill the bacterium? If we can unlock that, then we can unlock new therapies and unlock new vaccines.”

The only TB vaccine now available, the BCG vaccine, is a weakened version of a bacterium that causes TB in cows. This vaccine is widely administered in some parts of the world, but it poorly protects adults against pulmonary TB. Although some treatments are available, tuberculosis still kills more than a million people every year.

“To me, making a better TB vaccine comes down to a question of measurement, and so we have really tried to tackle that problem head-on. The mission of my lab is to develop new measurement modalities and concepts that can help us accelerate a better TB vaccine,” says Bryson, who is also a member of the Ragon Institute of Mass General Brigham, MIT, and Harvard.

From engineering to immunology

Engineering has deep roots in Bryson’s family: His great-grandfather was an engineer who worked on the Panama Canal, and his grandmother loved to build things and would likely have become an engineer if she had had the educational opportunity, Bryson says.

The oldest of four sons, Bryson was raised primarily by his mother and grandparents, who encouraged his interest in science. When he was three years old, his family moved from Worcester, Massachusetts, to Miami, Florida, where he began tinkering with engineering himself, building robots out of Styrofoam cups and light bulbs. After moving to Houston, Texas, at the beginning of seventh grade, Bryson joined his school’s math team.

As a high school student, Bryson had his heart set on studying biomedical engineering in college. However, MIT, one of his top choices, didn’t have a biomedical engineering program, and biological engineering wasn’t yet offered as an undergraduate major. After he was accepted to MIT, his family urged him to attend and then figure out what he would study.

Throughout his first year, Bryson deliberated over his decision, with electrical engineering and computer science (EECS) and aeronautics and astronautics both leading contenders. As he recalls, he thought he might study aero/astro with a minor in biomedical engineering and work on spacesuit design.

However, during an internship the summer after his first year, his mentor gave him a valuable piece of advice: “You should study something that will let you have a lot of options, because you don’t know how the world is going to change.”

When he came back to MIT for his sophomore year, Bryson switched his major to mechanical engineering, with a bioengineering track. He also started looking for undergraduate research positions. A poster in the hallway grabbed his attention, and he ended up with working with the professor whose work was featured: Linda Griffith, a professor of biological engineering and mechanical engineering.

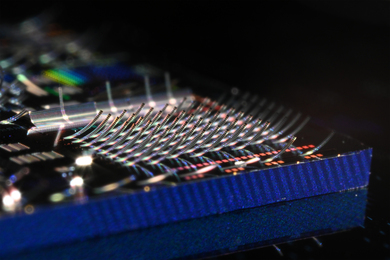

Bryson’s experience in the lab “changed the trajectory of my life,” he says. There, he worked on building microfluidic devices that could be used to grow liver tissue from hepatocytes. He enjoyed the engineering aspects of the project, but he realized that he also wanted to learn more about the cells and why they behaved the way they did. He ended up staying at MIT to earn a PhD in biological engineering, working with Forest White.

In White’s lab, Bryson studied cell signaling processes and how they are altered in diseases such as cancer and diabetes. While doing his PhD research, he also became interested in studying infectious diseases. After earning his degree, he went to work with a professor of immunology at the Harvard School of Public Health, Sarah Fortune.

Fortune studies tuberculosis, and in her lab, Bryson began investigating how Mycobacterium tuberculosis interacts with host cells. During that time, Fortune instilled in him a desire to seek solutions to tuberculosis that could be transformative — not just identifying a new antibiotic, for example, but finding a way to dramatically reduce the incidence of the disease. This, he thought, could be done by vaccination, and in order to do that, he needed to understand how immune cells response to the disease.

“That postdoc really taught me how to think bravely about what you could do if you were not limited by the measurements you could make today,” Bryson says. “What are the problems we really need to solve? There are so many things you could think about with TB, but what’s the thing that’s going to change history?”

Pursuing vaccine targets

Since joining the MIT faculty eight years ago, Bryson and his students have developed new ways to answer the question he posed in his faculty interviews: How does the immune system kill bacteria?

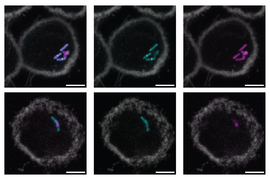

One key step in this process is that immune cells must be able to recognize bacterial proteins that are displayed on the surfaces of infected cells. Mycobacterium tuberculosis produces more than 4,000 proteins, but only a small subset of those end up displayed by infected cells. Those proteins would likely make the best candidates for a new TB vaccine, Bryson says.

Bryson’s lab has developed ways to identify those proteins, and so far, their studies have revealed that many of the TB antigens displayed to the immune system belong to a class of proteins known as type 7 secretion system substrates. Mycobacterium tuberculosis expresses about 100 of these proteins, but which of these 100 are displayed by infected cells varies from person to person, depending on their genetic background.

By studying blood samples from people of different genetic backgrounds, Bryson’s lab has identified the TB proteins displayed by infected cells in about 50 percent of the human population. He is now working on the remaining 50 percent and believes that once those studies are finished, he’ll have a very good idea of which proteins could be used to make a TB vaccine that would work for nearly everyone.

Once those proteins are chosen, his team can work on designing the vaccine and then testing it in animals, with hopes of being ready for clinical trials in about six years.

In spite of the challenges ahead, Bryson remains optimistic about the possibility of success, and credits his mother for instilling a positive attitude in him while he was growing up.

“My mom decided to raise all four of her children by herself, and she made it look so flawless,” Bryson says. “She instilled a sense of ‘you can do what you want to do,’ and a sense of optimism. There are so many ways that you can say that something will fail, but why don’t we look to find the reasons to continue?”

One of the things he loves about MIT is that he has found a similar can-do attitude across the Institute.

“The engineer ethos of MIT is that yes, this is possible, and what we’re trying to find is the way to make this possible,” he says. “I think engineering and infectious disease go really hand-in-hand, because engineers love a problem, and tuberculosis is a really hard problem.”

When not tackling hard problems, Bryson likes to lighten things up with ice cream study breaks at Simmons Hall, where he is an associate head of house. Using an ice cream machine he has had since 2009, Bryson makes gallons of ice cream for dorm residents several times a year. Nontraditional flavors such as passion fruit or jalapeno strawberry have proven especially popular.

“Recently I did flavors of fall, so I did a cinnamon ice cream, I did a pear sorbet,” he says. “Toasted marshmallow was a huge hit, but that really destroyed my kitchen.”