Removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere efficiently is often seen as a crucial need for combatting climate change, but systems for removing carbon dioxide suffer from a tradeoff. Chemical compounds that efficiently remove CO₂ from the air do not easily release it once captured, and compounds that release CO₂ efficiently are not very efficient at capturing it. Optimizing one part of the cycle tends to make the other part worse.

Now, using nanoscale filtering membranes, researchers at MIT have added a simple intermediate step that facilitates both parts of the cycle. The new approach could improve the efficiency of electrochemical carbon dioxide capture and release by six times and cut costs by at least 20 percent, they say.

The new findings are reported today in the journal ACS Energy Letters, in a paper by MIT doctoral students Simon Rufer, Tal Joseph, and Zara Aamer, and professor of mechanical engineering Kripa Varanasi.

“We need to think about scale from the get-go when it comes to carbon capture, as making a meaningful impact requires processing gigatons of CO₂,” says Varanasi. “Having this mindset helps us pinpoint critical bottlenecks and design innovative solutions with real potential for impact. That’s the driving force behind our work.”

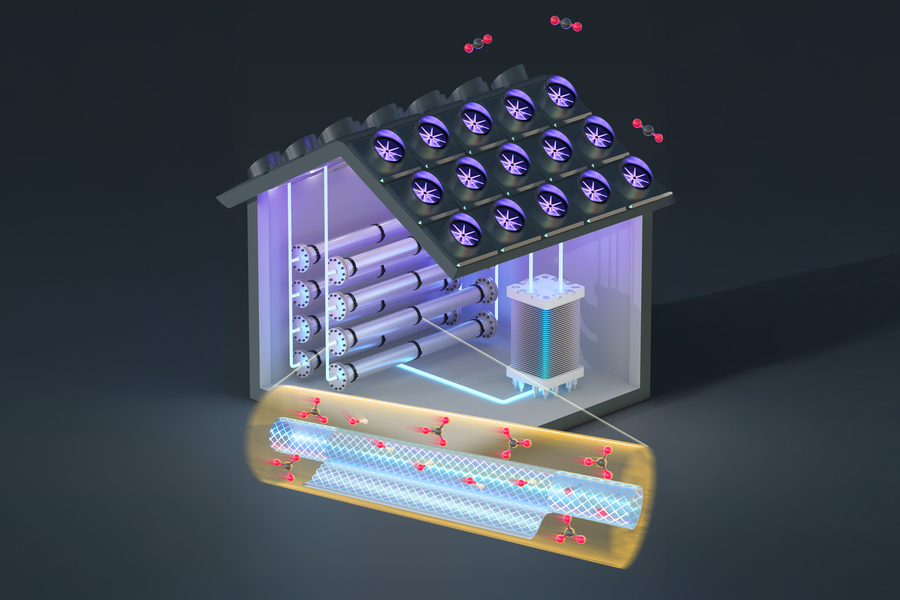

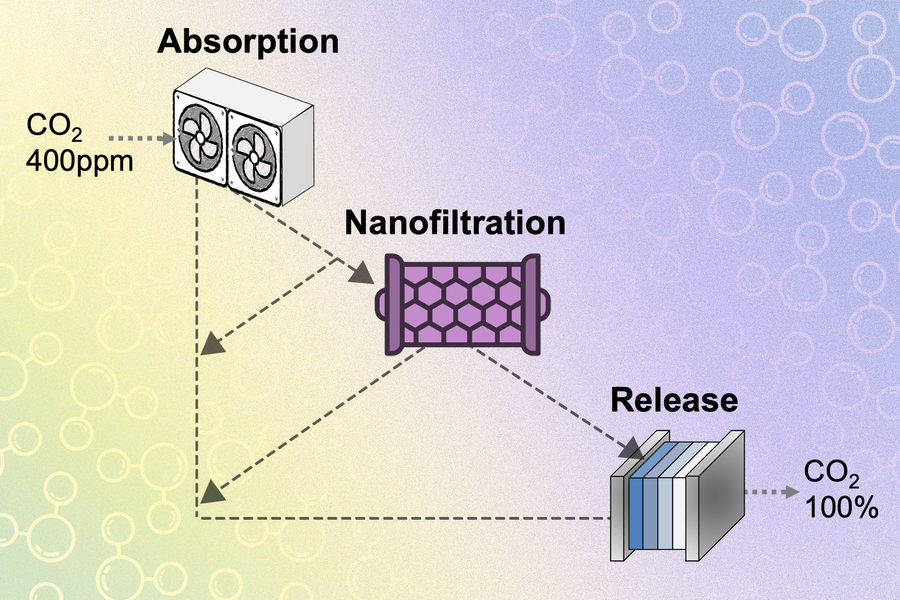

Many carbon-capture systems work using chemicals called hydroxides, which readily combine with carbon dioxide to form carbonate. That carbonate is fed into an electrochemical cell, where the carbonate reacts with an acid to form water and release carbon dioxide. The process can take ordinary air with only about 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide and generate a stream of 100 percent pure carbon dioxide, which can then be used to make fuels or other products.

Both the capture and release steps operate in the same water-based solution, but the first step needs a solution with a high concentration of hydroxide ions, and the second step needs one high in carbonate ions. “You can see how these two steps are at odds,” says Varanasi. “These two systems are circulating the same sorbent back and forth. They’re operating on the exact same liquid. But because they need two different types of liquids to operate optimally, it’s impossible to operate both systems at their most efficient points.”

The team’s solution was to decouple the two parts of the system and introduce a third part in between. Essentially, after the hydroxide in the first step has been mostly chemically converted to carbonate, special nanofiltration membranes then separate ions in the solution based on their charge. Carbonate ions have a charge of 2, while hydroxide ions have a charge of 1. “The nanofiltration is able to separate these two pretty well,” Rufer says.

Once separated, the hydroxide ions are fed back to the absorption side of the system, while the carbonates are sent ahead to the electrochemical release stage. That way, both ends of the system can operate at their more efficient ranges. Varanasi explains that in the electrochemical release step, protons are being added to the carbonate to cause the conversion to carbon dioxide and water, but if hydroxide ions are also present, the protons will react with those ions instead, producing just water.

“If you don’t separate these hydroxides and carbonates,” Rufer says, “the way the system fails is you’ll add protons to hydroxide instead of carbonate, and so you’ll just be making water rather than extracting carbon dioxide. That’s where the efficiency is lost. Using nanofiltration to prevent this was something that we aren’t aware of anyone proposing before.”

Testing showed that the nanofiltration could separate the carbonate from the hydroxide solution with about 95 percent efficiency, validating the concept under realistic conditions, Rufer says. The next step was to assess how much of an effect this would have on the overall efficiency and economics of the process. They created a techno-economic model, incorporating electrochemical efficiency, voltage, absorption rate, capital costs, nanofiltration efficiency, and other factors.

The analysis showed that present systems cost at least $600 per ton of carbon dioxide captured, while with the nanofiltration component added, that drops to about $450 a ton. What’s more, the new system is much more stable, continuing to operate at high efficiency even under variations in the ion concentrations in the solution. “In the old system without nanofiltration, you’re sort of operating on a knife’s edge,” Rufer says; if the concentration varies even slightly in one direction or the other, efficiency drops off drastically. “But with our nanofiltration system, it kind of acts as a buffer where it becomes a lot more forgiving. You have a much broader operational regime, and you can achieve significantly lower costs.”

He adds that this approach could apply not only to the direct air capture systems they studied specifically, but also to point-source systems — which are attached directly to the emissions sources such as power plant emissions — or to the next stage of the process, converting captured carbon dioxide into useful products such as fuel or chemical feedstocks. Those conversion processes, he says, “are also bottlenecked in this carbonate and hydroxide tradeoff.”

In addition, this technology could lead to safer alternative chemistries for carbon capture, Varanasi says. “A lot of these absorbents can at times be toxic, or damaging to the environment. By using a system like ours, you can improve the reaction rate, so you can choose chemistries that might not have the best absorption rate initially but can be improved to enable safety.”

Varanasi adds that “the really nice thing about this is we’ve been able to do this with what’s commercially available,” and with a system that can easily be retrofitted to existing carbon-capture installations. If the costs can be further brought down to about $200 a ton, it could be viable for widespread adoption. With ongoing work, he says, “we’re confident that we’ll have something that can become economically viable” and that will ultimately produce valuable, saleable products.

Rufer notes that even today, “people are buying carbon credits at a cost of over $500 per ton. So, at this cost we’re projecting, it is already commercially viable in that there are some buyers who are willing to pay that price.” But by bringing the price down further, that should increase the number of buyers who would consider buying the credit, he says. “It’s just a question of how widespread we can make it.” Recognizing this growing market demand, Varanasi says, “Our goal is to provide industry scalable, cost-effective, and reliable technologies and systems that enable them to directly meet their decarbonization targets.”

The research was supported by Shell International Exploration and Production Inc. through the MIT Energy Initiative, and the U.S. National Science Foundation, and made use of the facilities at MIT.nano.