Audio

Aggressive T-cell lymphoma is a rare and devastating form of blood cancer with a very low five-year survival rate. Patients often relapse after receiving initial therapy, making it especially challenging for clinicians to keep this destructive disease in check.

In a new study, researchers from MIT, in collaboration with researchers involved in the PETAL consortium at Massachusetts General Hospital, identified a practical and powerful prognostic marker that could help clinicians identify high-risk patients early, and potentially tailor treatment strategies to improve survival.

The team found that, when patients relapse within 12 months of initial therapy, their chances of survival decline dramatically. For these patients, targeted therapies might improve their chances for survival, compared to traditional chemotherapy, the researchers say.

According to their analysis, which used data collected from thousands of patients all over the world, the finding holds true across patient subgroups, regardless of the patient’s initial therapy or their score in a commonly used prognostic index.

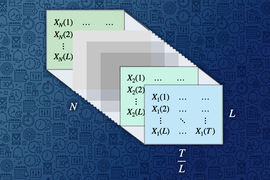

A causal inference framework called Synthetic Survival Controls (SSC), developed as part of MIT graduate student Jessy (Xinyi) Han’s thesis, was central to this analysis. This versatile framework helps to answer “when-if” questions — to estimate how the timing of outcomes would shift under different interventions — while overcoming the limitations of inconsistent and biased data.

The identification of novel risk groups could guide clinicians as they select therapies to improve overall survival. For instance, a clinician might prioritize early-phase clinical trials over canonical therapies for this cohort of patients. The results could inform inclusion criteria for some clinical trials, according to the researchers.

The causal inference framework for survival analysis can also be applied more broadly. For instance, the MIT researchers have used it in areas like criminal justice to study how structural factors drive recidivism.

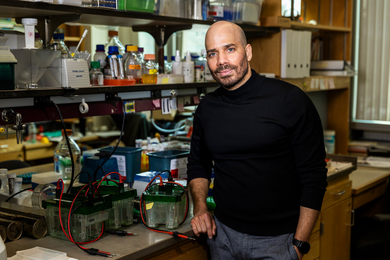

“Often we don’t only care about what will happen, but when the target event will happen. These when-if problems have remained under the radar for a long time, but they are common in a lot of domains. We’ve shown here that, to answer these questions with data, you need domain experts to provide insight and good causal inference methods to close the loop,” says Devavrat Shah, the Andrew and Erna Viterbi Professor in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT, a member of Institute for Data, Systems and Society (IDSS) and of the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems (LIDS), and co-author of the study.

Shah is joined on the paper by many co-authors, including Han, who is co-advised by Shah and Fotini Christia, the Ford International Professor of the Social Sciences in the Department of Political Science and director of IDSS; and corresponding authors Mark N. Sorial, a clinical pharmacist and investigator at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and Salvia Jain, a clinician-investigator at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, founder of the global PETAL consortium, and an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. The research appears today in the journal Blood.

Estimating outcomes

The MIT researchers have spent the past few years developing the Synthetic Survival Control causal inference framework, which enables them to answer complex “when-if” questions when using available data is statistically challenging. Their approach estimates when a target event happens if a certain intervention is used.

In this paper, the researchers investigated an aggressive cancer called nodal mature T-cell lymphoma, and whether a certain prognostic marker led to worse outcomes. The marker, TTR12, signifies that a patient relapsed within 12 months of initial therapy.

They applied their framework to estimate when a patient will die if they have TTR12, and how their survival trajectory would be different if they do not have this prognostic marker.

“No experiment can answer that question because we are asking about two outcomes for the same patient. We have to borrow information from other patients to estimate, counterfactually, what a patient’s survival outcome would have been,” Han explains.

Answering these types of questions is notoriously difficult due to biases in the available observational data. Plus, patient data gathered from an international cohort bring their own unique challenges. For instance, a clinical dataset often contains some historical data about a patient, but at some point the patient may stop treatment, leading to incomplete records.

In addition, if a patient receives a specific treatment, that might impact how long they will survive, adding to the complexity of the data. Plus, for each patient, the researchers only observe one outcome on how long the patient survives — limiting the amount of data available.

Such issues lead to suboptimal performance of many classical methods.

The Synthetic Survival Control framework can overcome these challenges. Even though the researchers don’t know all the details for each patient, their method stitches information from multiple other patients together in such a way that it can estimate survival outcomes.

Importantly, their method is robust to specific modeling assumptions, making it broadly applicable in practice.

The power of prognostication

The researchers’ analysis revealed that TTR12 patients consistently had much greater risk of death within five years of initial therapy than patients without the marker. This was true no matter the initial therapy the patients received or which subgroup they fell into.

“This tells us that early relapse is a very important prognosis. This acts as a signal to clinicians so they can think about tailored therapies for these patients that can overcome resistance in second-line or third-line,” Han says.

Moving forward, the researchers are looking to expand this analysis to include high-dimensional genomics data. This information could be used to develop bespoke treatments that can avoid relapse within 12 months.

“Based on our work, there is already a risk calculation tool being used by clinicians. With more information, we can make it a richer tool that can provide more prognostic details,” Shah says.

They are also applying the framework to other domains.

For instance, in a paper recently presented at the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, the researchers identified a dramatic difference in the recidivism rate among prisoners of different races that begins about seven months after release. A possible explanation is the different access to long-term support by different racial groups. They are also investigating individuals’ decisions to leave insurance companies, while exploring other domains where the framework could generate actionable insights.

“Partnering with domain experts is crucial because we want to demonstrate that our methods are of value in the real world. We hope these tools can be used to positively impact individuals across society,” Han says.

This work was funded, in part, by Daiichi Sankyo, Secure Bio, Inc., Acrotech Biopharma, Kyowa Kirin, the Center for Lymphoma Research, the National Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Reid Fund for Lymphoma Research, the American Cancer Society, and the Scarlet Foundation.