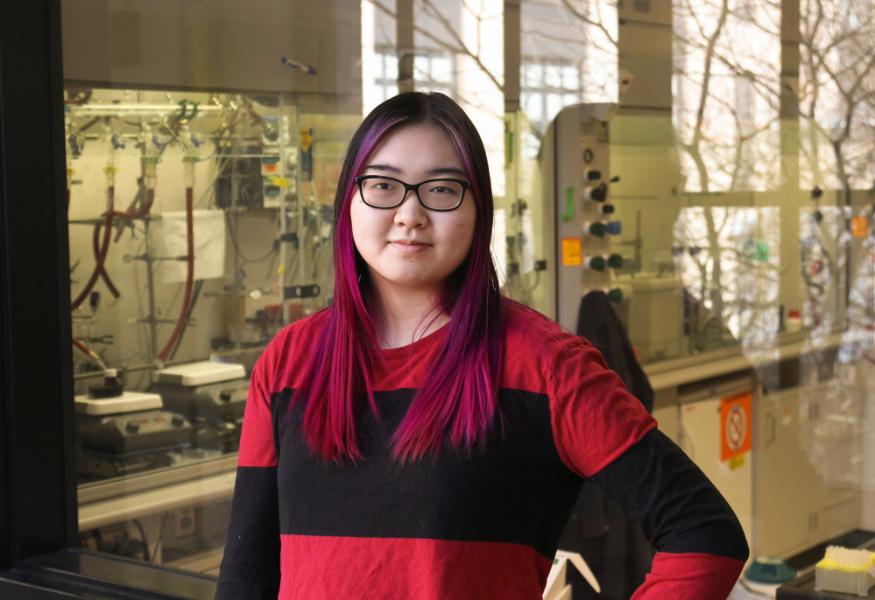

Senior Madison Wang, a double major in creative writing and chemistry, developed her passion for writing in middle school. Her interest in chemistry fit nicely alongside her commitment to producing engaging narratives.

Wang believes that world-building in stories supported by science and research can make for a more immersive reader experience.

“In science and in writing, you have to tell an effective story,” she says. “People respond well to stories.”

A native of Buffalo, New York, Wang applied early action for admission to MIT and learned quickly that the Institute was where she wanted to be. “It was a really good fit,” she says. “There was positive energy and vibes, and I had a great feeling overall.”

The power of science and good storytelling

“Chemistry is practical, complex, and interesting,” says Wang. “It’s about quantifying natural laws and understanding how reality works.”

Chemistry and writing both help us “see the world’s irregularity,” she continues. Together, they can erase the artificial and arbitrary line separating one from the other and work in concert to tell a more complete story about the world, the ways in which we participate in building it, and how people and objects exist in and move through it.

“Understanding magnetism, material properties, and believing in the power of magic in a good story … these are why we’re drawn to explore,” she says. “Chemistry describes why things are the way they are, and I use it for world-building in my creative writing.”

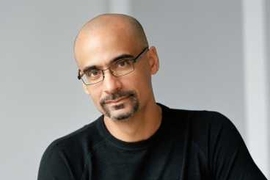

Wang lauds MIT’s creative writing program and cites a course she took with Comparative Media Studies/Writing Professor and Pulitzer Prize winner Junot Díaz as an affirmation of her choice. Seeing and understanding the world through the eyes of a scientist — its building blocks, the ways the pieces fit and function together — help explain her passion for chemistry, especially inorganic and physical chemistry.

Wang cites the work of authors like Sam Kean and Knight Science Journalism Program Director Deborah Blum as part of her inspiration to study science. The books “The Disappearing Spoon” by Kean and “The Poisoner’s Handbook” by Blum “both present historical perspectives, opting for a story style to discuss the events and people involved,” she says. “They each put a lot of work into bridging the gap between what can sometimes be sterile science and an effective narrative that gets people to care about why the science matters.”

Genres like fantasy and science fiction are complementary, according to Wang. “Constructing an effective world means ensuring readers understand characters’ motivations — the ‘why’ — and ensuring it makes sense,” she says. “It’s also important to show how actions and their consequences influence and motivate characters.”

As she explores the world’s building blocks inside and outside the classroom, Wang works to navigate multiple genres in her writing, as with her studies in chemistry. “I like romance and horror, too,” she says. “I have gripes with committing to a single genre, so I just take whatever I like from each and put them in my stories.”

In chemistry, Wang favors an environment in which scientists can regularly test their ideas. “It’s important to ground chemistry in the real world to create connections for students,” she argues. Advancements in the field have occurred, she notes, because scientists could exit the realm of theory and apply ideas practically.

“Fritz Haber’s work on ammonia synthesis revolutionized approaches to food supply chains,” she says, referring to the German chemist and Nobel laureate. “Converting nitrogen and hydrogen gas to ammonia for fertilizer marked a dramatic shift in how farming could work.” This kind of work could only result from the consistent, controlled, practical application of the theories scientists consider in laboratory environments.

A future built on collaboration and cooperation

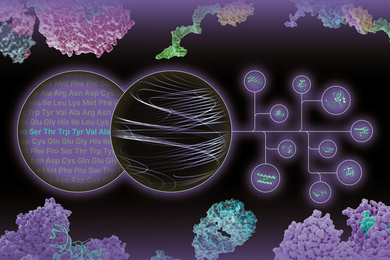

Watching the world change dramatically and seeing humanity struggle to grapple with the implications of phenomena like climate change, political unrest, and shifting alliances, Wang emphasizes the importance of deconstructing silos in academia and the workplace. Technology can be a tool for harm, she notes, so inviting more people inside previously segregated spaces helps everyone.

Criticism in both chemistry and writing, Wang believes, are valuable tools for continuous improvement. Effective communication, explaining complex concepts, and partnering to develop long-term solutions are invaluable when working at the intersection of history, art, and science. In writing, Wang says, criticism can help define areas to improve writers’ stories and shape interesting ideas.

“We’ve seen the positive results that can occur with effective science writing, which requires rigor and fact-checking,” she says. “MIT’s cross-disciplinary approach to our studies, alongside feedback from teachers and peers, is a great set of tools to carry with us regardless of where we are.”

Wang explores connections between science and stories in her leisure time, too. “I’m a member of MIT’s Anime Club and I enjoy participating in MIT’s Sport Taekwondo Club,” she says. The competitive aspect in tae kwon do allows for her to feed her competitive drive and gets her out of her head. Her participation in DAAMIT (Digital Art and Animation at MIT) creates connections with different groups of people and gives her ideas she can use to tell better stories. “It’s fascinating exploring others’ minds,” she says.

Wang argues that there’s a false divide between science and the humanities and wants the work she does after graduation to bridge that divide. “Writing and learning about science can help,” she asserts. “Fields like conservation and history allow for continued exploration of that intersection.”

Ultimately, Wang believes it’s important to examine narratives carefully and to question notions of science’s inherent superiority over humanities fields. “The humanities and science have equal value,” she says.