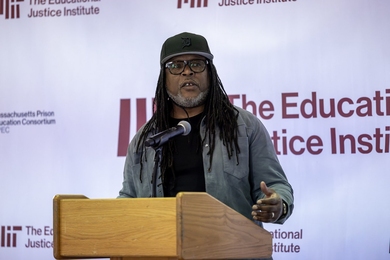

MIT philosophy doctoral student Abe Mathew believes individual rights play an important role in protecting the autonomy we value. But he also thinks we risk serious dysfunction if we ignore the importance of supporting and helping others.

“We should also acknowledge another feature of our moral lives,” he says, “namely, our need for affinity or closeness with other human beings, and our continued reliance on them to live flourishing lives in the world.”

Philosophy can be an important tool in understanding how humans interact with one another, he says. “I study moral obligation and rights, how the two relate, and the role they have to play in how we relate to one another,” Mathew adds.

Mathew asks that we think of autonomy and affinity as opposing forces — an idea he attributes to MIT philosopher, professor, and mentor Kieran Setiya. Autonomy pushes people farther from us, and affinity pulls people closer, Mathew says.

“The dance between autonomy and affinity creates morality,” Mathew adds.

Mathew is investigating one of moral philosophy’s foundational ideas — that every obligation we owe to another person correlates to a right that they have against us. The “Correlativity Thesis” is widely taken for granted, he says.

“A common example that's used to motivate the Correlativity Thesis is a case of a promise,” Mathew explains. “If I promise to meet you for coffee at 11, then I have a moral obligation to meet you for coffee at 11, and you have a right to meet me at 11.” While Mathew believes this is how promising works, he doesn’t think the Correlativity Thesis is true across the board.

“There isn’t necessarily a one-to-one relationship between rights and obligations,” he said. “A pregnant person on the bus may not have a right to your seat, but you do have an obligation to give it up for them.”

“We need folks’ help to do things”

Before coming to MIT, Mathew majored in philosophy and minored in ethics, law, and society as an undergraduate at the University of Toronto. Upon graduating in 2020, he was awarded the prestigious John Black Aird Scholarship, given each year to the university’s top undergraduate.

Now at MIT, Mathew says his research is based on the value of shared responsibility.

“We need folks’ help to do things,” he says.

When we lose sight of moral values, our societal connections can fall away, he argues.

“Mutual cooperation makes our lives possible,” Mathew says.

His research suggests alternatives to the idea that rights demand obligations.

“Morality puts a certain kind of pressure on us to ‘pay it forward’ — it requires us to do for others what was once done for us,” Mathew says. “If we don’t, we’re making an exception of ourselves; in essence, we're saying, ‘I was worthy of that help from others, but no one else is worthy of being helped by me.’”

Mathew also values the notion of paying it forward because he’s seen its value in his life. “I’ve encountered so many people who’ve gone above and beyond that I owe them,” he says.

A valuable social compact

Mathew has been extensively involved in “public philosophy.” For example, he’s organized public events at MIT, like the successful “Ask a Philosopher Anything” panel in the Stata Center lobby.

Mathew’s work leading the local chapter of Corrupt the Youth, a philosophy outreach program focused on bringing philosophy to high schools students from historically marginalized groups, is an extension of his belief in our shared responsibility for one another — of “paying it forward.”

“The reason I discovered philosophy was because of my instructors in college who not only introduced me to the subject, but also cultivated my enthusiasm for it and mentored me,” he says. “Our moral theorizing should take into account the kinds of creatures we are: vulnerable human beings who are constantly in need of each other to get by in the world,” Mathew says. One aspect of our vulnerability is our tendency to make mistakes, and as a result, damage our relationships with one another. Morality, Mathew says, gives us a tool — the social practice of forgiving — through which we can coexist, repair relationships we damage, and lead our lives together.

Mathew wants moral philosophers to consider their ideas’ practical, real-world applications. His experiences derive, in part, from notions of moral responsibility. Those who’ve been given a lot, he believes, have a greater responsibility for others. These kinds of social systems can consistently be improved by paying good deeds forward, he says.

“Moral philosophy should help build a world that allows for our mutual benefit,” Mathew says.