Growing up in Wallingford, Connecticut, David Darrow loved spending time outside, hiking and camping with his Boy Scout troop. He was fascinated by the environment around him, constantly asking questions about the natural world.

Now a senior at MIT majoring in math and minoring in German and physics, Darrow is still studying natural phenomena. With fluid dynamics and climate modeling as his primary fields of interest, he loves to use math as a way to explore the world around him.

“I see math as the language that the universe operates within. It is a very cool way to understand how nature works,” he says.

Darrow’s introduction to mathematical research at MIT started when he was a senior in high school, through the MIT PRIMES research program for high school students. Under the guidance of two mentors, he worked to come up with a new algorithm to simulate fluid movement more accurately and efficiently in a cylinder. While the project was ultimately unsuccessful, mathematically speaking, it galvanized his interest in the field — with failures included.

Beginning his first year at MIT, Darrow undertook numerous research projects on everything from minimal surface theory to convex geometry. While some were successful, others were not. Darrow says the failures have been some of his biggest challenges — and inspirations for new research ideas.

“That’s one of the big things about math research: Sometimes it just fails and there is nothing you can do about it. But if these things didn’t fail, it wouldn’t be interesting to study them in the first place,” he says.

In the spring of his junior year, Darrow worked alongside postdoc Daniel Alvarez-Gavela to study the symplectic topology of homotopy spheres. This was Darrow’s first project working side-by-side with someone else; his previous research experiences had been more independently driven.

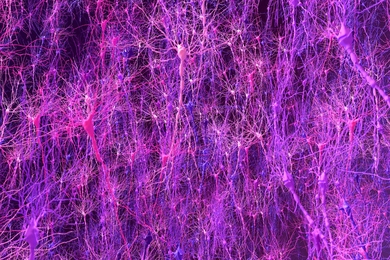

Darrow is currently studying protein folding with PhD candidate George Stepaniants, using statistical geometry to study and compare the differences between the folds of these large, complex molecules. Using catalogued data, he hopes to see if certain proteins are related and share an evolutionary past.

Darrow has also discovered a second passion during his time at MIT: language. Beginning with German in his first year, he is now learning Russian and French and revisiting Spanish, which he began studying in high school. His interest in these languages is partly driven by the fact that many of the subjects he is interested in were pioneered in languages other than English. Thus, by learning languages such as German and Spanish, he can connect to more people in mathematics and learn from their research. He also understands that some experts are more comfortable conversing in their native language, so he might miss out on valuable information — about math or many other topics.

“There are a lot of people you can’t connect with if you don’t speak the same language they do,” he says.

Darrow has also been working to present his own research in other languages. For example, in the spring of his junior year, he gave a presentation on one of his research projects about convex geometry in Spanish at the Víctor Neumann-Lara colloquium in Mexico. He has also submitted work to two French journals with the hopes of being published.

The pandemic has also increased Darrow’s appreciation for languages, as he sees the value of the internet as a learning tool for online education. Using programs like Duolingo and MIT Open Courseware himself, he understands the far-reaching potential that accessible and user-friendly platforms have to revolutionize learning, specifically in subjects like math and science.

“There are a lot of people in the U.S. who have language barriers, or partial language barriers, which makes traditional U.S. education very difficult. If you aren’t 100 percent comfortable with English, then learning calculus in English is going to be much tougher — to no fault of your own,” he says.

Darrow enjoys tutoring in all subjects, seeing it as a way to further his love of education and learning. “I think education is a big part of the research process,” he says.

Darrow is currently a mentor for MIT PRIMES, where he is helping a student design a research project aimed at developing a new way to measure how much force is being applied to joints in different situations. He also instructs in how to properly read and interpret articles and other conducted experiments related to the project.

In graduate school, Darrow hopes to study how fluid dynamics relate to the climate, looking at things like geophysical fluid flows and oceanographic modelling. He sees math, and fluid dynamics specifically, as a way to help predict and better respond to changes caused by climate issues.

“A lot of that comes down to how good our models are and how good our math is,” he says.

Darrow’s end goal is to go into academia, using his experience in mentorship and teaching to make himself a better teacher and researcher.

“I think it’s important to try to apply your skills to do something good, but also help other people get there themselves,” he says.