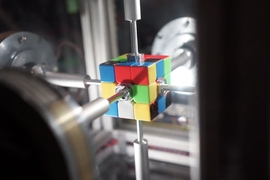

“Good night, Kev. Think big.” His father smiled, tucking him in and closing the door. The next day, 13-year-old Kevin Costello III arrived for the first time to MIT. But his visit wasn’t for the average campus tour. Costello, a three-time Rubik’s Cube national champion, had come to compete.

Tension grew in the competition room as the final round approached. Costello knew he had less than six seconds to solve the cube drawing from the 300 solving algorithms he had memorized. To stay calm, he turned toward a reliable source of comfort — music. Popping in his headphones, he felt his chest relax as he gained the confidence to pull off another win.

Today, Costello is a senior studying both mathematics and music. Though he knew he loved STEM and puzzles from a young age, it took time for Costello to recognize the importance of music in his life.

“I picked up trombone in fourth grade but was never very serious about it. As I entered high school, a lot of my friends were passionate musicians that inspired me to start practicing more,” he says. “Eventually, we started a jazz band to play gigs around town. We probably didn’t sound very good, but it kindled my love and appreciation for playing music.”

Upon arriving to MIT, Costello struggled to decide how he wanted to incorporate music into his college experience. His decision became clear when he chose his combined major. “I thought for a bit that I’d just do math. But as I took more music classes, I realized it was important to me to have a music major as well. I needed both in my life. I was lucky that the math major was flexible in that way,” he says.

Costello grew more confident with his decision after each new music class. Courses like 21M.226 (Jazz History) and 21M.292 (Music of Indonesia) opened his eyes to aspects of music he had never considered before. “I became introduced to musicology, which looks at music through the lenses of society and culture,” he recalls. “It was all so new and interesting to me.”

Costello continued with music performance by joining MIT Festival Jazz Ensemble (FJE). He discovered the group after watching their legendary performance with Grammy-winning musician Jacob Collier. Through FJE, he met other passionate musicians, many of whom would become his closest friends. Costello has been with the group ever since and currently serves as its co-president.

In the role, he has encouraged members to have more conversations about the larger impact of jazz. “We’ve discussed important topics, such as how jazz relates to sexism, gender, and Black American culture. These topics came up a lot in my classes, so I found it very important to talk about as an ensemble too,” he says.

When he isn’t studying or rehearsing songs, Costello enjoys applying his creativity to composing music of his own. The composition process allows his interests in mathematics and music to unite. “The two require a similar mindset. I’ll have an idea for a tune and then I’ll have to think about where I can take it next, just like in a math problem,” explains Costello. Some of his completed pieces have been performed by his friends in FJE. Costello loves watching his fellow musicians give his piece their all during opening night.

College has been a time for Costello to expand his passion for Rubik’s Cubes as well. He is currently the president of MIT Rubik’s Cube Club. His new focus has been teaching cubing to local middle school students. Costello tries to inspire kids by sharing his story — how he went from watching how-to videos on YouTube to eventually becoming the 4x4 national champion. In his message, he never fails to share his father’s advice of dreaming big.

Costello has watched his journey with cubing come full circle. He has organized two major Rubik’s Cube competitions held at MIT, just like the one he attended as a kid. The competitions have continued to introduce him to competitors from all over the world, many of whom are musicians.

“I’ve actually met a lot of fellow jazz players through cubing, which surprised me at first,” he says. “But what I’ve seen is that people interested in cubing tend to be pretty passionate people, which extends into other hobbies too.”

His combined interests also come alive through Costello’s research. The work, called computational musicology, applies automated methods to uncover mysteries underlying 13th-century French liturgy music. His pursuit was inspired by taking 21M.220 (Medieval and Renassance Music), where he was one of only four students.

“The small environment helped me really get to know my professor, Michael Cuthbert, who advises the project I work on now,” he explains. “I had no idea of the lasting impact the class would have on me.”

After classifying over 2,000 polyphonic works from this era, Costello has found new evidence regarding the history of “word painting,” a technique where musical sound mimics the song’s lyrics. Although the technique was previously thought to have arisen during the 16th century, his analysis shows word painting might have had earlier origins. The finding helps uncover the story of how music has evolved from the past to today.

“It’s interesting to me to hear how musical rules have transformed [over the centuries]. It’s also a reminder that we have so much more to explore,” he says.

Looking beyond his upcoming graduation, Costello is currently on the job hunt. He hopes to find more music-related research opportunities in the future, although he says it can be a niche field. Despite the field’s competition, Costello cites this as his dream career. “If I can be doing music research in the future, that would make me very happy. I would love to help find new ways to combine technology and music.”

Whether he pursues music research professionally or not, Costello plans to always channel his imagination and creativity through his passions. He is currently working on a concept for an interactive Rubik’s Cube that plays music. “If the cube were very scrambled, the music would be equally eccentric,” he explains. “As you get closer to solving it, the music would even out and gain consonance.”

That same inner spark will also continue to find an outlet through Costello’s musical compositions. The storytelling process lets him share his love for dreaming big in a different way. Through subtle harmonies, Costello’s message to his audience is clear.

“I try to set the listener up with some deceptive measures. They get these ideas about ways they think the piece will go, maybe that it’ll quiet down. Then comes the part I find most intriguing: Give them everything you’ve got.”