When Independent Activities Period (IAP) rolls around in January, it’s a welcome break from the daily grind of the semester — and not just for students. There’s only one problem, and it’s been that way since IAP began 50 years ago: deciding what to do. A stand-up comedy crash course or MIT Heavy Metal 101? Learning Estonian or making a pinball machine? In addition to academic subjects, the term is jam-packed with hundreds of workshops, events, lectures, recitals, competitions, classes, and other activities.

“One of the wonderful things about IAP for students — and it goes back to why it was created — is it allows undergraduates and graduate students an opportunity to spend time at MIT, or elsewhere, and not focus on their academic pursuit that brought them here,” says Elizabeth Cogliano Young, associate dean and director of the Office of the First Year. “Whether they are taking advantage of an IAP activity or not is kind of a moot point. It’s the fact that the month exists.”

In fact, IAP did not exist until 1971, when it was launched as an experiment. At the time, the Institute was in the midst of a period of educational innovation that produced novel programs like Interphase and the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program. Grading policies, the science General Institute Requirements curriculum, and the academic calendar were being re-examined, as well.

Senior faculty and administrators were particularly concerned that the academic calendar was causing undue stress for students. Fall semester finals took place after the holidays, so students had to spend their winter break studying, and the spring semester started shortly afterward. A committee tasked with considering calendar options proposed moving finals before the holidays and creating a January term that would allow “fallow time” for students. The faculty approved the proposal as a three-year experiment to begin in 1971. It was so successful that IAP was adopted as a permanent fixture in 1973 — and it has thrived in the past five decades.

Bucking tradition

From its inception, IAP has been open to the entire MIT community; anyone is welcome to propose almost any activity they wish. That’s given rise to a bevy of eclectic offerings over the years, from Palm Reading and Chili Chemistry to Yiddish Language and Culture and to How to Use a Slide Rule.

It has also enabled students to interact with faculty in less traditional ways. For 33 years, Professor Linn Hobbs shared his considerable wine expertise through In Vino Veritas, a wine-tasting class that was so popular it was oversubscribed every year, he says. Hobbs estimates that between 1982 and 2014, when he retired, he taught over 2,500 students.

The class met for three hours over the course of five evenings. Each time, participants sampled 12 wines metered out in 30 milliliter increments (in beakers, naturally), supplemented by lots of crackers and Hobbs’s detailed lectures. Setting up and breaking down each class took hours, even with the help of several teaching assistants. Since the wines changed from year to year, he spent at least a month writing the tasting notes for the lectures each year, and countless hours securing the wine, especially older vintages.

“It was much more work than I would ever prepare for a whole semester subject,” recalls Hobbs, who is the John F. Elliott Professor of Materials Emeritus and an emeritus professor of nuclear engineering. The class was a labor of love, though — one that his students appreciated so much that he consistently received standing ovations at the last class.

Students enjoyed learning about the chemistry underlying the taste and smell of wine, he says. “It required them to be very analytical, finding out about structures and compositions and chemistries. If you apply that to something like wine, you’ll know much more than most people — even people that drink a lot of wine. That’s what I wanted to show students, that they had these wonderful innate abilities, and can use wine tasting as a wonderful entrée into a kind of other social world. What the students loved about it was they could bring their own skills to this and be successful at it.”

A forum for new ideas

Freed from the pace and rigor of the semester, students, faculty, and staff over the years used the “extra” term to explore, experiment, and cultivate new ideas. LeaderShape is a prime example. Created in 1995, the program is a multi-day intensive leadership retreat for students, facilitated by faculty and staff. And it’s fertile ground for thinking outside the box. Ideas that have bubbled up at LeaderShape have paved the way for new programs at MIT, such as First-Year Pre-Orientation Programs and varsity women's ice hockey.

Early on, IAP also provided a venue for pivotal conversations about the climate for women at MIT — and ultimately, measures to improve it. In January 1972, some students grew concerned upon hearing that the administration did not intend to fill an open position for an associate dean of students, which had been recently vacated by Emily Wick, then professor of food science and nutrition, who had served as an important ally for women within the administration. Wick joined then-professor (and, later, Institute Professor) Mildred Dresselhaus in planning an IAP seminar to discuss the students’ concerns.

About 100 women — a mix of students, faculty, staff, postdocs, alumni, and faculty wives — attended, along with two men, in a meeting that Dresselhaus later described as a “semi-riot.” The meeting gave birth to what became known as the MIT Women’s Forum, which continued to meet regularly, ultimately becoming a formal organization that lasted for decades. The forum’s advocacy sparked significant change at MIT, such as the creation of an ad hoc committee to review the environment for women, and the appointment of a new position: special assistant to the president and chancellor for women and work.

A hotbed of competition

IAP wouldn’t be IAP without the plethora of games, contests, and tournaments offered over the past 50 years. Paper airplane contests and College Bowl tournaments. Hearts and Mahjong tournaments. Iconic events like Bad Ideas Weekend, Battlecode, and the 6.270 Autonomous Robot Competition. And that’s just a cursory sampling.

The MIT Mystery Hunt has been an IAP staple for 41 years. Over the course of a weekend, dozens of student teams solve hundreds of puzzles that lead to a metapuzzle. Cracking the metapuzzle reveals the location of a coin hidden on campus. In addition, the winning team earns the privilege of creating the hunt the following year.

For some, the competition is the stuff of legends. One MIT Admissions blogger, who at age 12 discovered the hunt on Wikipedia, recently wrote, “For the longest time, the only thing I knew about MIT was that it was the university that ran the Mystery Hunt, never mind the fact that it’s famous or whatever.” From then on he wanted to go to MIT “not to study or anything, but to participate in Mystery Hunt.”

Charmed, I’m sure

No tribute to IAP would be complete without a nod to Charm School. The idea was the brainchild of the late Dean for Academic Affairs Travis Merritt in 1993, as a way to help students master social graces.

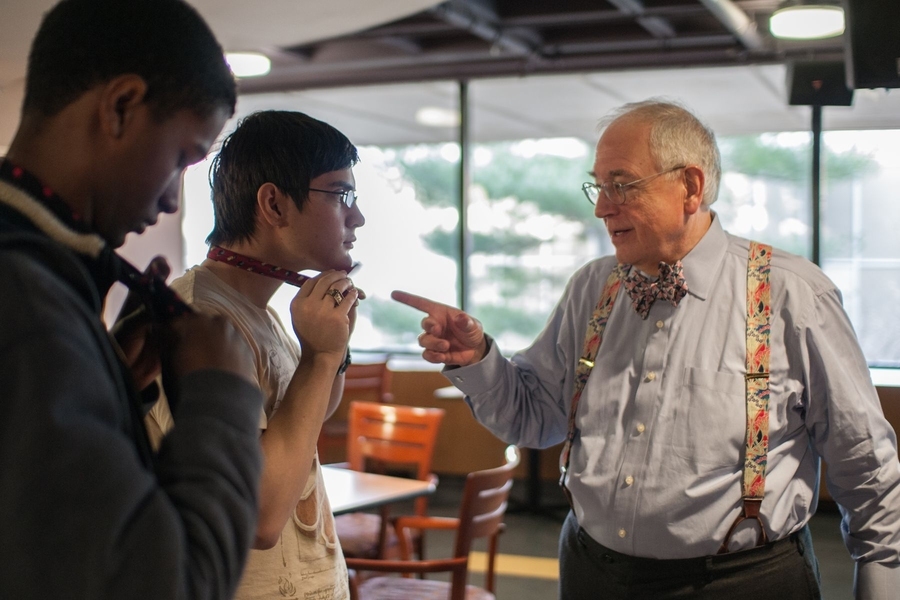

Held on the afternoon of the last Friday of IAP, Charm School featured different stations where hundreds of students learned important life skills like bathroom etiquette, making small talk, table manners, how to ask for a date, how to tie a bow tie, and buttering up big shots. “It was a real hubbub, and people always seemed to be interested,” says Robert Dimmick, now retired from the MIT Alumni Association, who taught bow tie tying for 10 years. In some years, fashion police circulated among the hundreds of students, issuing citations for violations like “using both straps on a back pack” and being a “walking jewelry store.”

Students collected charm credits at each station and the end of the afternoon they were awarded degrees in charm — six credits for a bachelor’s, eight for a master’s, and 12 for a ChD. Notable commencement speakers over the years included columnist Miss Manners (Judith Martin) in 1994 and the great-grandson of etiquette author Emily Post in 2004.

“Nobody at other colleges and universities had done anything like Charm School before,” recalls Dimmick, “so it got a lot of press.” In addition to the Boston Globe and Boston Herald, other news organizations featured Charm School as well, notably the Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, Scientific American, and the CBS “Sunday Morning” Show.

Unlimited possibilities (sort of)

Elizabeth Cogliano Young has had a window on IAP for 24 years now. Her office manages all the non-credit offerings, which involves reviewing hundreds of proposals submitted by students, faculty, and staff each year. She’s seen it all in that time. And that’s one of the great things about IAP, she says: Anyone can propose an activity that interests them. The sky is the limit — within reason, of course. Every few years, there’s an outlier, she says.

“We read each proposal before we approve it to make sure that no one is saying, “I want to brew beer in my bathtub, which is an actual thing that got submitted a number of years ago. We were like, ‘Yeah, you can’t do that. And telling us was probably not the smartest idea!’”