When MIT students walk into the Johnson Athletic Center for the fall career fair — or this year, hop onto Zoom — they're greeted with flashy displays from hundreds of employers vying for some of the top tech and engineering students in the world. Company reps eagerly tell them about salaries, office perks, and opportunities to contribute to cutting-edge work.

Now, thanks to a tool developed by MIT's Environmental Solutions Initiative (ESI), students can also learn how environmentally responsible their prospective employers are.

Sarah Meyers, ESI's education program manager, says ESI had heard from students interested in sustainability that the career fair gave them the impression they would have few employment options in that field.

“Even those big companies with sustainability divisions don't highlight the work they do,” says Meyers. “It's just not part of the norm.”

Students sometimes say they feel “lured into” lucrative fields like computer science, even if that's not what they wanted to do, she says. “For years now, we have known that MIT students are interested in working for companies that take environmental challenges seriously,” adds ESI Director John E. Fernández.

So Fernández asked Meyers to explore the development of a resource for the career fair to enable students to find meaningful positions at companies that prioritize sustainability.

Meyers thought a starting point could be rating whether or not companies were environmentally minded using environmental social governance (ESG) ratings. Companies that had high ESG scores would get a green leaf next to their name in the career fair handouts.

Sounds easy enough, but the results were puzzling. Exxon Mobil got a green leaf, while the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection did not. Meyers wondered whether this was because larger companies have the resources to hire teams to focus on ESG ratings.

To learn more about what was going on, the ESI team turned to Roberto Rigobon, a professor of applied economics at the MIT Sloan School of Management who had recently authored a paper on issues with ESG ratings. While credit ratings from Moody's and Standard & Poor correlate at .92 out of 1, meaning the same company would receive a similar score from different agencies, ESG ratings from five of the main agencies only correlate at .54.

Rigobon and his team found that there is too much variety in what categories are included in different ESG ratings and in how those categories are measured for them to be of much use to investors — or MIT students.

“I think that more transparency would be helpful, and more asking the investors (what they value) would be helpful,” Rigobon says.

He advised the ESI team to use emissions data to do their own analysis of the companies coming to the career fair.

Building the database

This summer, computer science, economics, and data science major Christopher Noga set out to do that by finding emissions and financial information from companies that had registered in past years for the career fair. This, too, would prove to be easier said than done.

Noga combed through company websites, financial statements, and reports made to the Carbon Disclosure Project, a nonprofit that encourages companies to report their environmental impacts. But he could only find emissions data for about a third of the companies, and many private companies did not have publicly available financial statements.

Some companies “really do hide what they do, how much they emit, and, in some cases, how much money they're making and where they're making it,” Noga says.

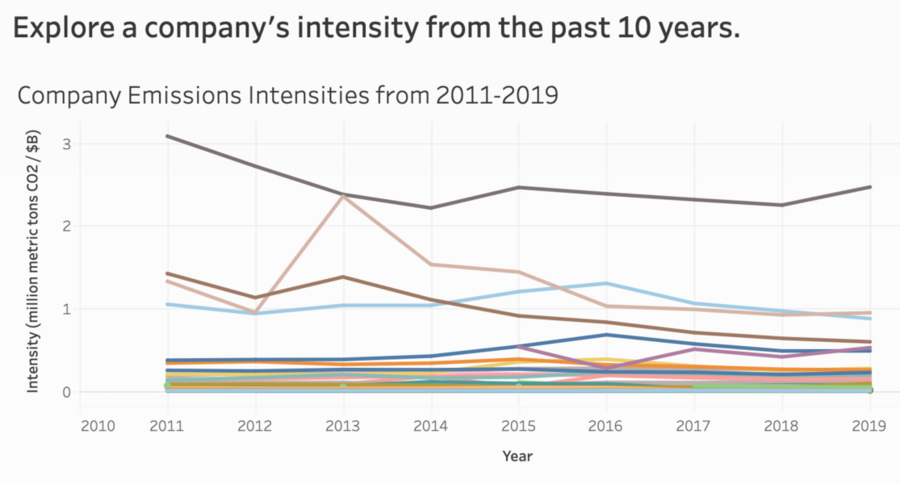

For the companies that had data, the ESI team divided total emissions by operating costs to measure each company’s “emissions intensity,” working with MIT Sloan to include historical data from 2011 on. This measurement allows students to better compare companies of different sizes, and see changes in emissions as companies grow, rather than just looking at total emissions.

Mining, fossil fuel, and manufacturing companies have the highest emissions intensity scores, while technology, health care, and government agencies have the lowest scores.

Meyers and Noga both emphasized limitations with the data, noting that they were struck by how little you know about a company just from looking at their emissions and financial statements. For example, the emissions intensity for Salesforce has been going up as they've grown, but the company also has plans to purchase 100% renewable electricity by 2022.

Surveying companies about their stance on climate change

To better get at the story behind the data, ESI worked with Oxford University to develop a four-question survey for the 238 companies who signed up for the career fair. The answers were revealing: for instance, only 8 percent of companies surveyed have a plan to get to net-zero emissions. Most strikingly, only 60 percent said they recognize the climate crisis and agree with climate science.

“That shocked me, that it wasn't just an easy 'yes',” Meyers says. She adds that this might just reflect that the employees who filled out the surveys were unaware of their company's stance on these issues, as many responded with “I don't know” rather than an outright no. Even so, this is a useful result, signaling to these companies that MIT is interested in their stance on climate change and that they should have an answer prepared in future years.

ESI also put together a list of questions for students to ask companies to learn more about their environmental and social responsibility practices.

“It seems like a real opportunity for students to become more engaged with the career fair and realize that they're able to ask questions of companies that they might have been intimidated to ask,” Meyers says.

All this work resulted in the MIT Career Fair Sustainability Initiative website, which students can visit to compare company emissions, and learn how to engage with potential employers about their environmental commitments.

Fernández, director of ESI, says that one of the main goals of this project is to communicate to students that they are an “enormously valuable asset” to employers.

“Companies want MIT students as employees,” says Fernández. “Therefore, our students are in a position to influence a company’s policies toward climate mitigation and their overall approach to sustainability. The career fair is the ideal venue through which MIT students can begin to express their values and interests to industry.”

So far, 359 people have visited the new site. Vivian Song '20, who worked with ESI to create the site, was surprised to learn that MIT was one of the only universities putting out this type of information about companies that come to the career fair.

“I think it would be great if MIT could help lead the way to encourage other universities to do something similar,” she says.