How might climate change alter the global food system by the year 2050? Will diets change to reflect a revamped agriculture designed to adapt to a warming world? MIT Joint Program Principal Research Scientist Erwan Monier and New York University artist Allie Wist grappled with these questions as they developed a dinner menu for the MIT Climate Changed Symposium, a two-day gathering of experts in the sciences, humanities and design focused on the role and impact of models in a changed climate.

Co-sponsored by the MIT Environmental Solutions Initiative and the MIT School of Architecture and Planning and organized by Irmak Turan and Jessica Varner, the symposium — along with an ideas competition and multimedia exhibition — examined how past, present, and future climate-related models can enable us to understand and design the built environment as significant changes unfold in the Earth system through and beyond mid-century.

Held at Café ArtScience in Kendall Square, the symposium dinner consisted of four courses, each representing a different landscape. Signifying the forest, the appetizer was a trio of dried, preserved, and foraged mushrooms, fungi known to help the soil store carbon dioxide and thus slow the pace of climate change.

The next two courses included two options — the first symbolizing more comfortable conditions that climate models project will prevail, on average, by the year 2050 under an ambitious greenhouse gas emissions reduction policy; the second suggesting more hardscrabble environments that the models indicate will likely result in the absence of climate action. For the first course, representing the desert, the choice was between a squash tart with sorghum honey or cactus fruit gel with dehydrated fruits. For the second, representing the ocean, all diners got to eat wild striped bass, with one half receiving their fish filleted and the other half having to contend with bones.

Suggesting melting sea ice and glaciers in an Arctic landscape, the dessert was a pine milk parfait infused with pine smoke and topped with fresh berries and a juniper tuile.

“Our menu selections were designed to reflect the idea that the impact of climate change on various landscapes will vary widely based on the level of climate action that will take place between now and the year 2050,” said Monier.

Prior to the dinner, Monier and Wist delivered a brief presentation on the complexity of modeling the global food system and the visualization of future food landscapes.

Monier noted that to address this complexity, Joint Program researchers integrate a diverse set of models that simulate different aspects of the food system, from atmospheric chemistry to water resource management to crop yields. He then highlighted three key challenges in modeling climate change over the coming decades.

First, how much climate change will we experience? Climate policy scenarios range from business-as-usual to stringent, translated for symposium guests as a more challenging or more comfortable dining experience. Second, how will different regions experience climate change? Monier observed that climate models project crop-yield increases and decreases for different regions of Africa — and that uncertainty in the models can produce a wide range of projections for some regions. This was translated into different landscape storylines for each of the four courses. Finally, how will we adapt to climate change?

“Depending on the severity of climate change, we will either be able to adapt to maintain our current diet,” said Monier, “or need to introduce or intensify the use of different drought-tolerant food sources such as seaweed and cactus.”

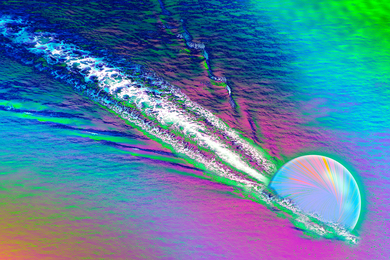

Monier also appears in the Climate Changed Exhibition, a work curated by Jessica Varner, Irmak Turan, and Irina Chernyakova, and produced by artist Rainar Aasrand and designers from Omnivore. The exhibition is a continuous-loop multimedia exploration of how computational models and design practices have enabled people to represent, understand, assess, communicate, and act upon climate change. On view April 6-May 19 in the Keller Gallery (Room 7-408), it shows how the feedback process between climate models and design has evolved since the development of the first general circulation model in the 1960s.

In multiple interview segments, Monier describes how Earth-system models of different resolution are used to assess environmental change at global and regional levels. He explains how the Joint Program’s signature Integrated Global System Modeling (IGSM) framework models different components of the Earth system and how they interact, and projects the impact of global environmental change (including climate change) on both Earth and human systems under different climate policy scenarios and degrees of uncertainty about the climate’s response to atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations.