When former NFL player Wade Davis, as a teenager, first told his mother that he was gay, he wasn’t prepared for the response he got: “You’re already black!” she told him, adding that she wished he would die of cancer rather than tell her he was gay.

Their relationship remained uncomfortable for years, Davis says, but eventually, after many difficult conversations, they came to better understand each other’s perspectives. Now, years later, he says his mom and his fiancé happily talk and text each other. That long and hard progression, he said, helped to give him insight into the need to ask deep questions and try to understand why other people with different views feel the way they do.

Davis, who now serves as the NFL’s first-ever LGBT inclusion consultant, described these experiences in the keynote address at the 44th annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. celebration luncheon, held at a packed Morss Hall on the MIT campus. He explained that he eventually learned that his mother had a much older brother who had been killed in a lynching. He finally understood that her harsh words were her way of trying to protect him from the prejudices and hatred she knew he would encounter in the world — and that she had experienced all too vividly.

“You have to have compassion for those you disagree with,” Davis said. In this case, he said, the breakthrough in understanding only came after “I asked my mother better questions.” Reflecting on a short poem by Langston Hughes, called “Personal,” Davis said this compassion is the key to effective action even when the path is difficult. “The work must become personal,” he said, as people struggle to bring greater justice and equity in the world.

In his own growth, he said, he came to realize that thinking that of oneself as a good person doesn’t really matter. “We’re so interested in our own goodness,” he said, but that’s not as important to others. “They don’t care if you think you’re a good person. What matters is what you’re doing.”

MIT President L. Rafael Reif, in his remarks introducing Davis, said that right now we live in “an angry, cynical time, in which many people are careless with the truth. … And sometimes it nearly breaks your heart.”

But, he said, “when I feel worn out by all the terrible noise, I take great inspiration in thinking about our community at MIT because, I would like to believe, MIT is different. MIT can be noisy, too. But it’s mostly the noise of bright, curious people testing old assumptions, coming up with new ideas, and trying to understand each other.”

“As for cynicism,” he added, “to me, cynicism could be a sign of defeat. It could be a sign that you have lost faith in human goodness and possibility, and lost faith in our creative power to make a better world. By that definition, MIT is the opposite of cynicism. And I am grateful for, and proud of, this community’s practical optimism, every day.”

Of course, MIT is not perfect, he said, but “I am very grateful to belong to a community that, I would like to think, is willing to face its imperfections, to talk honestly and openly about them, in a spirit of mutual respect, and to work together to make things better.”

Reif described significant progress MIT has made over the last two years in implementing new programs to foster inclusion and equity, including a $23.4 million increase in financial aid, new interactive sessions on diversity during undergraduate and graduate student orientation, and new mental health staff trained in “culturally competent” care.

“The harder, more systemic issues now become our central focus,” he added. “This includes the long-term challenge of recruiting more graduate students and faculty from underrepresented minority groups and making sure they are positioned to succeed. But we have the right people pursuing the right strategies … so I am optimistic that we can steadily turn these aspirations into action, too.”

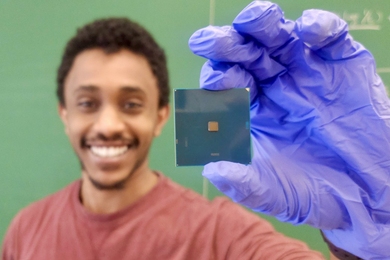

The luncheon also featured reflections on King’s legacy by two current MIT students. Josué Lopez, a fourth-year doctoral student in electrical engineering and computer science, said, “For the past decade, I have been trying to tackle climate change, via technology, education, and more recently, direct nonviolent action. As someone who grew up in a low-income and immigrant community in Los Angeles, I am painfully aware that communities of color are disproportionately affected by the devastating effects of climate change and environmental waste and pollution, otherwise known as environmental racism.”

Lopez added, “This year we tragically saw that the most vulnerable communities in Houston, Puerto Rico, and Dominica will take the longest to recover from the physical and psychological scars of devastating hurricanes strengthened by climate change. … The Puerto Rican student association and I all have family, friends, and communities that were affected. So it’s personal. This is why I understand that climate change is fundamentally an issue of equity and justice.”

He concluded by telling the gathering that “looking at all of you, I see individuals who want to work toward a more equitable future. Regardless of the state of American or global politics, we at MIT have opportunities to implement plans that will directly support equity and justice here and everywhere.”

“Most importantly, believe in your own ability to make a difference,” he said. “Believe that equity and social justice are worth fighting for. Believe that we will win in pursuing justice and equity, because we must!”

Tori Finney, a senior in electrical engineering and computer science, said that until recently, she had never reflected deeply on the influence of race on her own life and identity. Growing up, she spent eight years at an international school in Belgium where she only encountered five students of color. “It was a confusing time,” she said. “Both my racial and national identity were challenged. Classmates would comment that I was not ‘really black’ because I didn’t talk or act the way they saw black Americans act on TV, but I still somehow felt too black to fit in with some of them.”

She recalled,“We didn’t complain and further alienate ourselves when our next-door neighbor called the police on me for standing outside my own house when I was 12.” That and similar experiences “were upsetting to me, but I didn’t really understand why, or what I could possibly do to change anything,” she said.

Finney gradually became aware of the effects that microaggressions can have on a person’s mental health: “All at once, years’ worth of reactions to injustices against me came crashing down. I refer to this as an awokening.” At MIT, she said, “I went to mental health walk-in hours one afternoon, and was introduced to a new term: racial battle fatigue.”

This term, she said, “describes the stress and anxiety that many people of color develop while navigating a predominantly white institution. With racial microaggressions acting as the source of trauma, this mental health disorder is similar to PTSD. It can affect people both mentally and physically, often contributing to fatigue, hypertension, headaches, and sleep issues.”

Finney said, “While my focus today is mainly on the effects of racial microaggressions, I would like to mention that the problem extends beyond race. … I believe that there are countless MIT students that have similar problems based on gender identity, sexuality, religion, and other aspects of their identities.”

What should people do about these things? “We can increase informal dialogue,” Finney suggested. “We can spend more time asking people about what behavior they might find harmful. We can brainstorm icebreakers that will encourage people to talk about their differences in classes or meetings. In these conversations, we can respect the fact that something we thought was okay might not be okay for someone else. Instead of making excuses for it, we can learn what we need to do to change.”

Comparing injustice to air pollution, which can spread insidiously, she said, “If we all work together, we can cleanse our campus of the pollution of microaggressions. And in doing so, we can prevent it from spreading elsewhere.”