Women make up half the world’s population, but just 12 percent of the world’s heads of state and government. This disparity underscores a persistent reality in the 21st century: Despite steady advances in women’s rights in recent decades, gender norms and biases continue to constrain human potential around the world.

A growing number of policymakers believe that investing in women and girls’ empowerment can reduce these and other gender-based inequalities. The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal 5, for example, seeks to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Increasing empowerment is also seen as a promising strategy to unlock greater economic growth in low- and middle-income countries.

In order to design effective policies and programs, however, researchers, policymakers, and practitioners must be able to accurately measure women’s and girls’ empowerment. A new research resource from MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) addresses this challenge.

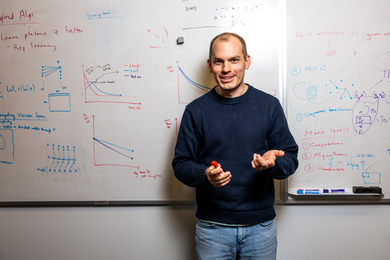

Co-authored by Rachel Glennerster, chief economist at the UK Department for International Development and former executive director of J-PAL; and Lucia Diaz-Martin and Claire Walsh of J-PAL, the “Practical Guide to Measuring Women’s and Girls’ Empowerment” offers guidance on strategies to help navigate and overcome common challenges in effectively measuring empowerment in impact evaluations.

Evaluating impact

Researchers can rarely observe people’s decision-making in real-time, and survey questions that ask study participants about decision-making do not always lead to reliable responses, particularly when questions touch on sensitive topics. For these reasons, it can be hard for researchers and practitioners to identify whether a social program or intervention actually increased people’s decision-making power, a common measure of empowerment.

Beyond survey challenges, questions arise around which outcomes best capture changes in empowerment. For example, should researchers focus on measuring educational attainment? Agency in household or community decision-making? Employment and control over income? Women and girls experience constraints that are deeply tied to their specific context. Because these constraints can vary so widely, what empowerment looks like for female students in Ghana might be very different from what it looks like for women living in a rural village in India. Researchers often grapple with how to generalize lessons learned from a particular program when what empowerment looks like can vary greatly around the world.

J-PAL’s new guide draws on strategies from multiple academic disciplines to tackle these measurement issues. Rich with case studies and concrete examples, it outlines actionable steps to improve measurement.

Determine local context

Understanding the local context is key. Before trying to measure empowerment in an impact evaluation, researchers must have a nuanced picture of the local context and the specific barriers that women face when trying to make meaningful choices about their own lives. Qualitative research methods such as semi-structured interviews, needs assessments, direct observation, and focus groups can help by creating repeated opportunities to listen closely to the people living in a particular community. A measurement strategy to quantify empowerment is only as good as researchers and practitioners’ understanding of gender and power dynamics in the local context.

In an evaluation in Bangladesh, for example, Glennerster and co-authors were interested in measuring adolescent girls’ mobility. After several focus groups with adolescent girls they learned that asking the generic question “How far away can you travel from home by yourself?” would not capture how a girl’s mobility was constrained, because the answer depended on what she was doing and for whom. Girls could travel to and from school alone, but they could not travel alone to do things that only had value to them, like going to local fairs. Since empowerment is about people’s abilities to make choices that matter to them, researchers added a question about mobility for activities that only had value to the adolescent girls in addition to the usual questions about going to school or visiting relatives.

Develop a theory for how intervention generates impact

Developing a clear theory of how an intervention generates impact can help researchers select accurate indicators of empowerment. To identify the outcomes of a women’s empowerment program (the change or impact we expect to see) and indicators (observable signals we use to measure that change), researchers and practitioners need a deep understanding of the pathways through which the program can affect people’s lives.

Mapping these pathways, from program inputs (like funding and staff time) to long-term outcomes, is also known as a “theory of change” and results in documentation of a program’s logical chain of results. This mapping process helps clarify appropriate measurement indicators, and helps researchers identify which assumptions must hold true for the program to succeed.

Develop a plan and carry out testing

Once researchers decide what outcomes to measure, they should develop and pilot data collection instruments in communities similar to ones where the evaluation will take place. This is an important reality check to make sure surveys work in local contexts.

For example, many commonly used survey questions to measure household decision-making are hard to ask and answer in practice. In Bangladesh, Glennerster and co-authors found that women gave very different answers to the general question, “Who usually makes decisions about healthcare for yourself: you, your husband, you and your husband jointly, or someone else?” and the more specific question, “If you ever need medicine, could you go buy it yourself?” Piloting different versions of a question can help researchers learn whether they are truly capturing the information they think they are.

Non-survey instruments can also be powerful for measuring things surveys can’t capture accurately — like gender bias. In a study on female leaders in India for example, researchers randomly assigned survey participants to hear one of two identical audio recordings of a short speech by a political leader, one spoken by a man and the other by a woman. They then asked participants to rate the leader’s effectiveness. Because the gender was the only difference between the two recordings, researchers could use this technique to measure bias against female leaders.

After researchers conduct a comprehensive pilot and incorporate lessons learned, they should design a practical data collection plan. Although data collection can be full of unexpected challenges, finding reliable, culturally appropriate, and convenient methods and times to collect survey data can help overcome measurement errors.

Why measure empowerment?

“If measurement techniques are inaccurate, it can be difficult to understand whether programs are effective, and how to improve on existing approaches,” says J-PAL’s Claire Walsh. Ensuring that measurement tools are reliable and precise can help researchers avoid drawing inaccurate conclusions about the impact of a program.

J-PAL recently announced new efforts to further expand the base of policy-relevant evidence related to gender and women’s empowerment. Alongside this research, J-PAL continues to create practical resources to support policymakers, practitioners, and researchers in effectively incorporating analysis of gender dynamics and impacts into their impact evaluations. For more information about this work, visit povertyactionlab.org/gender.