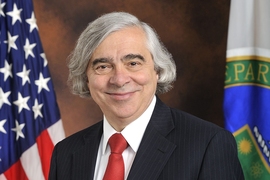

In his first official return to the MIT campus since taking the job of U.S. Secretary of Energy in 2013, former MIT physics professor and founding director of the MIT Energy Initiative Ernest J. Moniz spoke to the annual, student-run MIT Energy Conference on Friday, saying that the prospects for new jobs in energy-related fields are booming — and include roles for virtually every academic discipline.

The annual event, which is the largest student-run energy conference in the nation and is now in its 11th year, brings together leaders in energy technology, business, and policy from around the nation and the world. Moniz, who under federal guidelines was recused from involvement in any MIT activities for his first two years, said he was now taking advantage of the “brief window” between that recusal period and the end of President Obama’s term of office — and thus, presumably, his own term as well.

Moniz said that last fall’s climate conference in Paris “was, in my view, enormously successful.” He said that among the outcomes of that international conference, at which virtually every nation on Earth vowed to take measures toward a low-carbon future, “an important point to make is that innovation was placed at the heart of the climate change response.”

That central role for innovation was far from just talk, he stressed. The International Energy Agency calculated that the commitments reached in Paris will lead to about $1 trillion a year being invested in various nations’ efforts to pursue low-carbon technology. “It’s really a big deal!” he said.

Doubling of R&D

In addition, the 20 countries that already spend the lion’s share of all worldwide energy research and development money — representing some 80 to 85 percent of the global total — agreed to take part in a new “Mission Innovation,” which includes a commitment to double their annual research and development expenditures in this area. The number of countries that opted to join in this agreement, Moniz said, “far exceeded our expectations.”

Innovation, Moniz said, is “the essence of America’s strength.” In addition to the plan for doubling national investments in energy research, he said, there will also be a parallel effort, spearheaded by a group of 28 wealthy individuals from 10 countries, including Bill Gates, to form a group called the Breakthrough Energy Coalition, which will invest additional billions of dollars on energy research. The group aims “to increase the investment pipeline in these countries in a way that will maximize risk tolerance” — something that is necessary to bring about significant advances, but which traditional investors, whether private or governmental, tend to be wary of.

In fact, the track record for the Department of Energy’s research investments has been very good, Moniz said. Since the Advanced Research Projects Agency - Energy (ARPA-E) program to fund early-stage energy research was started after he took office, he said, after five years of investment about 200 projects have been funded, and about a quarter of those have gone on to raise a total of about $250 million in private funding. Yet it’s still not enough, he said. Last year, of the applications submitted for that program only 2 percent were funded, meaning that “we are still leaving a lot of innovations on the table.” The new Mission Innovation initiative, he said, hopes to help address that.

Creating new jobs

In addition to helping to address global climate change, these new energy investments will also create significant numbers of new jobs, both nationally and globally, he said. For example, the solar industry alone has created some 200,000 full-time jobs in the United States, and many more part-time jobs. “That is a big industry!” he said.

And the energy-related employment opportunities go well beyond just the obvious jobs in engineering and basic science research. There are also great opportunities for students interested in policy and analysis, he said. This is “a new way of doing business, based on really deep and fundamental analysis,” and there are great needs for people trained in economics, public policy, and a variety of other fields.

“We need innovations in science, innovations in technology, innovations in policy, innovations in business models,” Moniz said. Because all these roles are so important and interconnected, he said, when he and Robert Armstrong, who succeeded him as director of the MIT Energy Initiative (MITEI), were setting up that program, he said “we made sure that every school and every discipline was engaged” in that process. “That multidisciplinary approach has been so critical” to the program’s success, he said.

And in that vein, one of the first things he did when he assumed his present office, he explained, was to establish a new Office of Energy Policy and Systems Analysis, headed by Melanie Kenderdine, who had been MITEI’s executive director. That office now has 75 people, “quite a few” of them from MIT, he said.

Dealing with Iran

Moniz was asked about the pivotal role he played in last year’s successful negotiations with Iran over a deal on their nuclear programs. The process was helped greatly, he said, by the fact that he and Iran’s lead technical negotiator shared an MIT background, even though they hadn’t met here: Ali Akbar Salehi had earned his PhD in nuclear engineering at MIT. At one early session, learning that Salehi had recently celebrated the birth of a new grandchild, Moniz presented him with techie gifts including a onesie with the symbols for copper and tellurium (CuTe) on the front. Such negotiations are “so much about the relationship,” he said.

As for negotiations at home in the U.S., he said that while so much of this country’s politics has been polarized, “the innovation agenda has very significant bipartisan support.” For example, he noted, on the Republican side, Sen. Lindsay Graham has now put together an innovation caucus. “That’s quite positive,” he said.

The fact that China has committed to significant cuts in emissions, Moniz added, “was a total game changer,” since their failure to do so had been used “as an excuse” for inaction by U.S. lawmakers as long as China “wasn’t doing anything.”