Throughout human history, plants have been a source of potent medicines, including many cancer drugs discovered over the past few decades. However, it is quite difficult to discover such drugs and obtain them in large quantities from the plants or through chemical synthesis.

MIT researchers and collaborators from Tufts University have now engineered E. coli bacteria to produce large quantities of a critical compound that is a precursor to the cancer drug Taxol, originally isolated from the bark of the Pacific yew tree. The bacteria can produce 1,000 times more of the precursor, known as taxadiene, than any other engineered microbial strain.

The technique, described in the Oct. 1 issue of Science, could bring down the manufacturing costs of Taxol and also help scientists discover potential new drugs for cancer and other diseases such as hypertension and Alzheimer’s, said Gregory Stephanopoulos, who led the team of MIT and Tufts researchers and is one of the senior authors of the paper.

“If you can make Taxol a lot cheaper, that’s good, but what really gets people excited is the prospect of using our platform to discover other therapeutic compounds in an era of declining new pharmaceutical products and rapidly escalating costs for drug development,” said Stephanopoulos, the W.H. Dow Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT.

Taxol, also known as paclitaxel, is a powerful cell-division inhibitor commonly used to treat ovarian, lung and breast cancers. It is also very expensive — about $10,000 per dose, although the cost of manufacturing that dose is only a few hundred dollars. (Patients usually receive one dose.)

Two to four Pacific yew trees are required to obtain enough Taxol to treat one patient, so in the 1990s, bioengineers came up with a way to produce it in the lab from cultured plant cells, or by extracting key intermediates from plant material like the needles of the decorative yew. These methods generate enough material for patients, but do not produce sufficient quantities for synthesizing variants that may be far more potent for treating cancer and other diseases. Organic chemists have succeeded in synthesizing Taxol in the lab, but these methods involve 35 to 50 steps and have a very low yield, so they are not economical. Also, they follow a different pathway than the plants, which makes it impossible to produce the pathway intermediates and change them to make new, potentially more powerful variations.

“By mimicking nature, we can now begin to produce these intermediates that the plant makes, so people can look at them and see if they have any therapeutic properties,” said Stephanopoulos. Moreover, they can synthesize variants of these intermediates that may have therapeutic properties for other diseases.

Improving efficiency

The complex metabolic sequence that produces Taxol involves at least 17 intermediate steps and is not fully understood. The team's goal was to optimize production of the first two Taxol intermediates, taxadiene and taxadien-5-alpha-ol. E. coli does not naturally produce taxadiene, but it does synthesize a compound called IPP, which is two steps away from taxadiene. Those two steps normally occur only in plants. MIT postdoctoral associate Ajikumar Parayil recognized that the key to more efficient production is a well-integrated pathway that does not allow potentially toxic intermediates to accumulate. To accomplish this, researchers took a two-pronged approach in engineering E. coli to produce taxadiene.

First, the team examined the IPP pathway, which has eight steps, and focused on four of those reactions that had been determined to be bottlenecks in the synthesis — that is, there is not enough enzyme at those steps, so the entire process is slowed down. Parayil then engineered the bacteria to express multiple copies of those four genes, eliminating the bottlenecks and speeding up IPP production.

To get E. coli to convert IPP to taxadiene, the researchers added two plant genes, modified to function in bacteria, which code for the enzymes needed to perform the reactions. They also varied the number of copies of the genes to find the most efficient combination. These methods allowed the researchers to boost taxadiene production 1,000 times over levels achieved by other researchers using engineered E. coli, and 15,000 times over a control strain of E. coli to which they just added the two necessary plant genes but did not optimize gene expression of either pathway.

Following taxadiene synthesis, researchers advanced the pathway by adding one more critical step toward Taxol synthesis, the conversion of taxadiene to taxadien-5-alpha-ol. This is the first time that taxadien-5-alpha-ol has been produced in microbes. There are still several more steps to go before achieving synthesis of the intermediate baccatin III, from which Taxol can be chemically synthesized. “Though this is only a first step, it is a very promising development and certainly supports this approach and its potential," said Blaine Pfeifer, assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering at Tufts and an author of the Science paper.

Now that the researchers have achieved taxadiene synthesis, there are still another 15 to 20 steps to go before they can generate Taxol. In this study, they showed that they can perform the first of those steps.

Joseph Chappell, professor of plant sciences at the University of Kentucky, says the team’s yield of taxadiene is impressive, but the addition of several hydroxyl molecules, which is required to produce baccatin III, will likely prove more difficult. “They’re showing one (hydroxylation), but it remains to be seen if they’ll be able to couple this with the other hydroxylation events needed to build the baccatin III molecule,” he said.

Stephanopoulos and Pfeifer expect that if this technique can eventually be used to manufacture Taxol, it would reduce significantly the cost to produce one gram of the drug. Researchers could also experiment with using these bacteria to create other useful chemicals such as fragrances, flavors and cosmetics, said Pfeifer.

Development of the new technology was funded by the Singapore-MIT Alliance, National Institutes of Health and a Milheim Foundation Grant for Cancer Research. MIT has filed a patent on the technology and new strain of E. coli, and the researchers are considering licensing the technology or starting a new company to commercialize it, said Stephanopoulos.

Researchers engineer microbes for low-cost production of precursor of anticancer drug Taxol and other pharmaceuticals.

Publication Date:

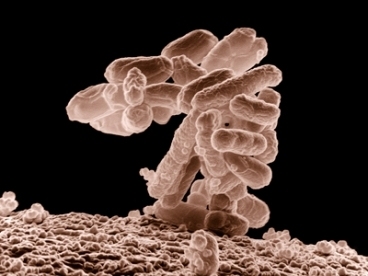

Caption:

A close-up view of E. coli.

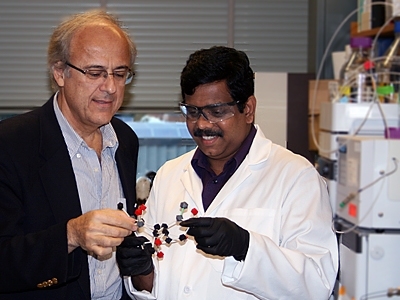

Caption:

Gregory Stephanopoulos, professor of chemical engineering, left, and postdoctoral associate Ajikumar Parayil have developed a new way to genetically engineer bacteria to produce a precursor to the cancer drug Taxol.

Credits:

Photo: Simon Carlsen