A longstanding goal of immunotherapies and vaccine research is to induce antibodies in humans that neutralize deadly viruses such as HIV and influenza. Of particular interest are antibodies that are “broadly neutralizing,” meaning they can in principle eliminate multiple strains of a virus such as HIV, which mutates rapidly to evade the human immune system.

Researchers at MIT and the Scripps Research Institute have now developed a vaccine that generates a significant population of rare precursor B cells that are capable of evolving to produce broadly neutralizing antibodies. Expanding these cells is the first step toward a successful HIV vaccine.

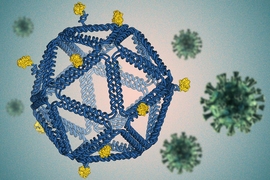

The researchers’ vaccine design uses DNA instead of protein as a scaffold to fabricate a virus-like particle (VLP) displaying numerous copies of an engineered HIV immunogen called eOD-GT8, which was developed at Scripps. This vaccine generated substantially more precursor B cells in a humanized mouse model compared to a protein-based virus-like particle that has shown significant success in human clinical trials.

Preclinical studies showed that the DNA-VLP generated eight times more of the desired, or “on-target,” B cells than the clinical product, which was already shown to be highly potent.

“We were all surprised that this already outstanding VLP from Scripps was significantly outperformed by the DNA-based VLP,” says Mark Bathe, an MIT professor of biological engineering and an associate member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. “These early preclinical results suggest a potential breakthrough as an entirely new, first-in-class VLP that could transform the way we think about active immunotherapies, and vaccine design, across a variety of indications.”

The researchers also showed that the DNA scaffold doesn’t induce an immune response when applied to the engineered HIV antigen. This means the DNA VLP might be used to deliver multiple antigens when boosting strategies are needed, such as for challenging diseases such as HIV.

“The DNA-VLP allowed us for the first time to assess whether B cells targeting the VLP itself limit the development of ‘on target’ B cell responses — a longstanding question in vaccine immunology,” says Darrell Irvine, a professor of immunology and microbiology at the Scripps Research Institute and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Bathe and Irvine are the senior authors of the study, which appears today in Science. The paper’s lead author is Anna Romanov PhD ’25.

Priming B cells

The new study is part of a major ongoing global effort to develop active immunotherapies and vaccines that expand specific lineages of B cells. All humans have the necessary genes to produce the right B cells that can neutralize HIV, but they are exceptionally rare and require many mutations to become broadly neutralizing. If exposed to the right series of antigens, however, these cells can in principle evolve to eventually produce the requisite broadly neutralizing antibodies.

In the case of HIV, one such target antibody, called VRC01, was discovered by National Institutes of Health researchers in 2010 when they studied humans living with HIV who did not develop AIDS. This set off a major worldwide effort to develop an HIV vaccine that would induce this target antibody, but this remains an outstanding challenge.

Generating HIV-neutralizing antibodies is believed to require three stages of vaccination, each one initiated by a different antigen that helps guide B cell evolution toward the correct target, the native HIV envelope protein gp120.

In 2013, William Schief, a professor of immunology and microbiology at Scripps, reported an engineered antigen called eOD-GT6 that could be used for the first step in this process, known as priming. His team subsequently upgraded the antigen to eOD-GT8. Vaccination with eOD-GT8 arrayed on a protein VLP generated early antibody precursors to VRC01 both in mice and more recently in humans, a key first step toward an HIV vaccine.

However, the protein VLP also generated substantial “off-target” antibodies that bound the irrelevant, and potentially highly distracting, protein VLP itself. This could have unknown consequences on propagating target B cells of interest for HIV, as well as other challenging immunotherapy applications.

The Bathe and Irvine labs set out to test if they could use a particle made from DNA, instead of protein, to deliver the priming antigen. These nanoscale particles are made using DNA origami, a method that offers precise control over the structure of synthetic DNA and allows researchers to attach viral antigens at specific locations.

In 2024, Bathe and Daniel Lingwood, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and a principal investigator at the Ragon Institute, showed this DNA VLP could be used to deliver a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in mice to generate neutralizing antibodies. From that study, the researchers learned that the DNA scaffold does not induce antibodies to the VLP itself, unlike proteins. They wondered whether this might also enable a more focused antibody response.

Building on these results, Romanov, co-advised by Bathe and Irvine, set off to apply the DNA VLP to the Scripps HIV priming vaccine, based on eOD-GT8.

“Our earlier work with SARS-CoV-2 antigens on DNA-VLPs showed that DNA-VLPs can be used to focus the immune response on an antigen of interest. This property seemed especially useful for a case like HIV, where the B cells of interest are exceptionally rare. Thus, we hypothesized that reducing the competition among other irrelevant B cells (by delivering the vaccine on a silent DNA nanoparticle) may help these rare cells have a better chance to survive,” Romanov says.

Initial studies in mice, however, showed the vaccine did not induce sufficient early B cell response to the first, priming dose.

After redesigning the DNA VLPs, Romanov and colleagues found that a smaller diameter version with 60 instead of 30 copies of the engineered antigen dramatically out-performed the clinical protein VLP construct, both in overall number of antigen-specific B cells and the fraction of B cells that were on-target to the specific HIV domain of interest. This was a result of improved retention of the particles in B cell follicles in lymph nodes and better collaboration with helper T cells, which promote B cell survival.

Overall, these improvements enabled the particles to generate eightfold more on-target B cells than the vaccine consisting of eOD-GT8 carried by a protein scaffold. Another key finding, elucidated by the Lingwood lab, was that the DNA particles promoted VRC01 precursor B cells toward the VRC01 antibody more efficiently than the protein VLP.

“In the field of vaccine immunology, the question of whether B cell responses to a targeted protective epitope on a vaccine antigen might be hindered by responses to neighboring off-target epitopes on the same antigen has been under intense investigation,” says Schief, who is also vice president for protein design at Moderna. “There are some data from other studies suggesting that off-target responses might not have much impact, but this study shows quite convincingly that reducing off-target responses by using a DNA VLP can improve desired on-target responses.”

“While nanoparticle formulations have been great at boosting antibody responses to various antigens, there is always this nagging question of whether competition from B cells specific for the particle’s own structural antigens won’t get in the way of antibody responses to targeted epitopes,” says Gabriel Victora, a professor of immunology, virology, and microbiology at Rockefeller University, who was not involved in the study. “DNA-based particles that leverage B cells’ natural tolerance to nucleic acids are a clever idea to circumvent this problem, and the research team’s elegant experiments clearly show that this strategy can be used to make difficult epitopes easier to target.”

A “silent” scaffold

The fact that the DNA-VLP scaffold doesn’t induce scaffold-specific antibodies means that it could be used to carry second and potentially third antigens needed in the vaccine series, as the researchers are currently investigating. It also might offer significantly improved on-target antibodies for numerous antigens that are outcompeted and dominated by off-target, irrelevant protein VLP scaffolds in this or other applications.

“A breakthrough of this paper is the rigorous, mechanistic quantification of how DNA-VLPs can ‘focus’ antibody responses on target antigens of interest, which is a consequence of the silent nature of this DNA-based scaffold we’ve previously shown is stealth to the immune system,” Bathe says.

More broadly, this new type of VLP could be used to generate other kinds of protective antibody responses against pandemic threats such as flu, or potentially against chemical warfare agents, the researchers suggest. Alternatively, it might be used as an active immunotherapy to generate antibodies that target amyloid beta or tau protein to treat degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, or to generate antibodies that target noxious chemicals such as opioids or nicotine to help people suffering from addiction.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health; the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard; the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; the National Science Foundation; the Novo Nordisk Foundation; a Koch Institute Support (core) Grant from the National Cancer Institute; the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; the Gates Foundation Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery; the IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; and the U.S. Army Research Office through MIT’s Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies.