Gemstones like precious opal are beautiful to look at and deceivingly complex. As you look at such gems from different angles, you’ll see a variety of tints glisten, causing you to question what color the rock actually is. It’s iridescent thanks to something called structural color — microscopic structures that reflect light to produce radiant hues.

Structural color can be found across different organisms in nature, such as on the tails of peacocks and the wings of certain butterflies. Scientists and artists have been working to replicate this quality, but outside of the lab, it’s still very hard to recreate, causing a barrier to on-demand, customizable fabrication. Instead, companies and individual designers alike have resorted to adding existing color-changing objects like feathers and gems to things like personal items, clothes, and artwork.

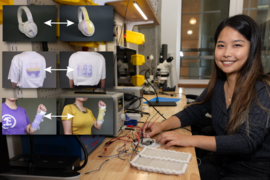

Now MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) researchers have replicated nature’s brilliance with a new optical system called “MorphoChrome.” MorphoChrome allows users to design and program iridescence onto everyday objects (like a glove, for example), augmenting them with the structurally colored multi-color glimmer reminiscent of many gemstones. You select particular colors from a color wheel in the team’s software program and use their handheld device to “paint” with multi-color light onto holographic film. Then, you apply that painted sheet to 3D-printed objects or flexible substrates such as fashion items, sporting goods, and other personal accessories, using their unique epoxy resin transfer process.

“We wanted to tap into the innate intelligence of nature,” says MIT Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) PhD student and CSAIL researcher Paris Myers SM ’25, who is a lead author on a recent paper presenting MorphoChrome. “In the past, you couldn’t easily synthesize structural color yourself, but using pigments or dyes gave you full creative expression. With our system, you have full creative agency over this new material space, predictably programming iridescent designs in real-time.”

MorphoChrome showed it could add a luminous touch to things like a necklace charm of a butterfly. What started as a static, black accessory became a shiny pendant with green, orange, and blue glimmers, thanks to the system’s programmable color process. MorphoChrome also turned golfing gloves into beginner-friendly training equipment that shine green when you hold a golf club at the correct angle, and even helped one user adorn their fingernails with a gemstone-like look.

These multi-color displays are the result of a handheld fabrication process where MorphoChrome acts as a “brush" to paint with red-green-blue (RGB) laser light, while a holographic photopolymer film (used for things like passports and debit cards) is the canvas. Users first connect the system’s handheld device to a computer via a USB-C port, then open the software program. They can then click “send color” to rapidly transmit different hues from their laptop or home computer to the MorphoChrome hardware tool.

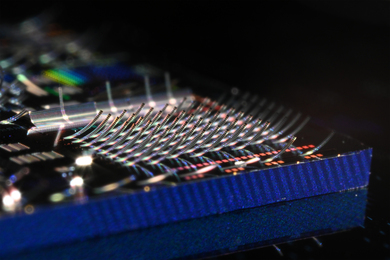

This handheld device transforms the colors on a screen into a controllable, multi-color RGB laser light output that instantly exposes the film, a sort of canvas where users can explore different combinations of hues. About the size of a glue bottle, MorphoChrome’s optical machine houses red, green, and blue lasers, which are activated at various intensities depending on the color chosen. These lights are reflected off mirrors toward an optical prism, where the colors mix and are promptly released as a single combined beam of light.

After designing the film, one can fabricate diverse structurally colored objects by first coating a chosen object with a thin layer of epoxy resin. Next, the holographic film (litiholographics) — composed of a photopolymer layer and a protective plastic backing — is bonded to the object through a 20-second ultraviolet cure, essentially using a handheld UV light to transfer the colored design onto the surface. Finally, users peel off the film’s protective plastic sheet, revealing a color-changing, structurally-colored object that looks like a jewel.

Do try this at home

MorphoChrome is surprisingly user-friendly, consisting of a straightforward fabrication blueprint and an easy-to-use device that encourages do-it-yourself designers and other makers to explore iridescent designs at home. Instead of spending time searching for hard-to-find artistic materials or chemically synthesizing structural color in the lab, users can focus on expressing various ideas and experimenting with programming different radiant color mixes.

The array of possible colors stems from intriguing fusions. Nagenta, for instance, is created after the system’s blue and red lasers mix. Selecting cyan on the MorphoChrome software’s color wheel will mix the green and blue lights.

Users should note that the time it takes to fully expose the film to each color will vary, based on the researchers’ multi-color findings and the intrinsic properties of holographic photopolymer film. MorphoChrome activates green in 2.5 seconds, whereas red takes about 3 seconds, and blue needs roughly 6 seconds to saturate. The reason for this discrepancy is that each color is a particular wavelength of light, requiring a certain level of light exposure (blue needing more than green or red).

Look at this hologram

MorphoChrome builds upon previous work on stretchable structural color by co-author Benjamin Miller PhD ’24, Professor Mathias Kolle, and Kolle’s Laboratory for Biologically Inspired Photonic Engineering group at MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering. The CSAIL researchers, who work in the Human-Computer Interaction Engineering Group, say that MorphoChrome also advances their ongoing work on merging computation with unique materials to create dynamic, programmable color interfaces.

Going forward, their goal is to push the capabilities of holographic structural color as a reprogrammable design and manufacturing space, empowering individuals and industries alike to customize iridescent and diffuse multi-color interfaces. “The polymer sheet we went with here is holographic, which has potential beyond what we’re showing here,” says co-author Yunyi Zhu ’20, MEng ’21, who is an MIT EECS PhD student and CSAIL researcher. “We’re working on adapting our process for creating entire 3D light fields in one film.”

Customizing full light-field holographic messages onto objects would allow users to encode information and 3D images. One could imagine, for example, that a passport could have a sticker that beams out a 3D green check mark. This hologram would signal its authenticity when viewed through a particular device or at a certain angle.

The team is also inspired by how animals use structural color as an adaptive communication channel and camouflage technique. Going forward, they are curious how programmable structural color could be integrated into different types of environments, perhaps as camouflage for soft robotic structures to blend into an environment. For instance, they imagine a robot studying jungle terrain may need to match the appearance of nearby bushes to collect data, with a human reprogramming the machine’s color from afar.

In the meantime, MorphoChrome recreates the majestic structural color found in various ecosystems, connecting a natural phenomenon with our creative processes. MIT researchers will look to improve the system’s color gamut and maximize how luminous mixed colors are. They’re also considering using another material for the device’s casing, since its current 3D-printing housing leaks out some light.

“Being able to easily create and manipulate structural color is a great new tool, and opens up new avenues for discovery and expression,” says Liti Holographics CEO Paul Christie SM ’97, who wasn’t involved in the research. “Simplifying the process to be more easily accessible allows for new applications to be developed in a wider range of areas, from art and jewelry to functional fabric.”

Myers, Zhu, and Miller wrote the paper with senior author Stefanie Mueller, who is an MIT associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science and CSAIL principal investigator. Their research was supported by the National Science Foundation, and presented as a demo paper and poster at the 2025 ACM Symposium on Computational Fabrication in November.