How can artificial intelligence step out of a screen and become something we can physically touch and interact with?

That question formed the foundation of class 4.043/4.044 (Interaction Intelligence), an MIT course focused on designing a new category of AI-driven interactive objects. Known as large language objects (LLOs), these physical interfaces extend large language models into the real world. Their behaviors can be deliberately generated for specific people or applications, and their interactions can evolve from simple to increasingly sophisticated — providing meaningful support for both novice and expert users.

“I came to the realization that, while powerful, these new forms of intelligence still remain largely ignorant of the world outside of language,” says Marcelo Coelho, associate professor of the practice in the MIT Department of Architecture, who has been teaching the design studio for several years and directs the Design Intelligence Lab. “They lack real-time, contextual understanding of our physical surroundings, bodily experiences, and social relationships to be truly intelligent. In contrast, LLOs are physically situated and interact in real time with their physical environment. The course is an attempt to both address this gap and develop a new kind of design discipline for the age of AI.”

Given the assignment to design an interactive device that they would want in their lives, students Jacob Payne and Ayah Mahmoud focused on the kitchen. While they each enjoy cooking and baking, their design inspiration came from the first home computer: the Honeywell 316 Kitchen Computer, marketed by Neiman Marcus in 1969. Priced at $10,000, there is no record of one ever being sold.

“It was an ambitious but impractical early attempt at a home kitchen computer,” says Payne, an architecture graduate student. “It made an intriguing historical reference for the project.”

“As somebody who likes learning to cook — especially now, in college as an undergrad — the thought of designing something that makes cooking easy for those who might not have a cooking background and just wants a nice meal that satisfies their cravings was a great starting point for me,” says Mahmoud, a senior design major.

“We thought about the leftover ingredients you have in the refrigerator or pantry, and how AI could help you find new creative uses for things that you may otherwise throw away,” says Payne.

Generative cuisine

The students designed their device — named Kitchen Cosmo — with instructions to function as a “recipe generator.” One challenge was prompting the LLM to consistently acknowledge real-world cooking parameters, such as heating, timing, or temperature. One issue they worked out was having the LLM recognize flavor profiles and spices accurate to regional and cultural dishes around the world to support a wider range of cuisines. Troubleshooting included taste-testing recipes Kitchen Cosmo generated. Not every early recipe produced a winning dish.

“There were lots of small things that AI wasn't great at conceptually understanding,” says Mahmoud. “An LLM needs to fundamentally understand human taste to make a great meal.”

They fine-tuned their device to allow for the myriad ways people approach preparing a meal. Is this breakfast, lunch, dinner, or a snack? How advanced of a cook are you? How much meal prep time do you have? How many servings will you make? Dietary preferences were also programmed, as well as the type of mood or vibe you want to achieve. Are you feeling nostalgic, or are you in a celebratory mood? There’s a dial for that.

“These selections were the focal point of the device because we were curious to see how the LLM would interpret subjective adjectives as inputs and use them to transform the type of recipe outputs we would get,” says Payne.

Unlike most AI interactions that tend to be invisible, Payne and Mahmoud wanted their device to be more of a “partner” in the kitchen. The tactile interface was intentionally designed to structure the interaction, giving users a physical control over how the AI responded.

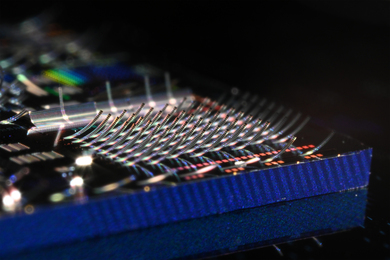

“While I’ve worked with electronics and hardware before, this project pushed me to integrate the components with a level of precision and refinement that felt much closer to a product-ready device,” says Payne of the course work.

Retro and red

After their electronic work was completed, the students designed a series of models using cardboard until settling on the final look, which Payne describes as “retro.” The body was designed in a 3D modeling software and printed. In a nod to the original Honeywell computer, they painted it red.

A thin, rectangular device about 18 inches in height, Kitchen Cosmo has a webcam that hinges open to scan ingredients set on a counter. It translates these into a recipe that takes into consideration general spices and condiments common in most households. An integrated thermal printer delivers a printed recipe that is torn off. Recipes can be stored in a plastic receptacle on its base.

While Kitchen Cosmo made a modest splash in design magazines, both students have ideas where they will take future iterations.

Payne would like to see it “take advantage of a lot of the data we have in the kitchen and use AI as a mediator, offering tips for how to improve on what you’re cooking at that moment.”

Mahmoud is looking at how to optimize Kitchen Cosmo for her thesis. Classmates have given feedback to upgrade its abilities. One suggestion is to provide multi-person instructions that give several people tasks needed to complete a recipe. Another idea is to create a “learning mode” in which a kitchen tool — for example, a paring knife — is set in front of Kitchen Cosmo, and it delivers instructions on how to use the tool. Mahmoud has been researching food science history as well.

“I’d like to get a better handle on how to train AI to fully understand food so it can tailor recipes to a user’s liking,” she says.

Having begun her MIT education as a geologist, Mahmoud’s pivot to design has been a revelation, she says. Each design class has been inspiring. Coelho’s course was her first class to include designing with AI. Referencing the often-mentioned analogy of “drinking from a firehou

“For the first time, in that class, I felt like I was finally drinking as much as I could and not feeling overwhelmed. I see myself doing design long-term, which is something I didn’t think I would have said previously about technology.”