When the Venice Biennale’s 19th International Architecture Exhibition launches on May 10, its guiding theme will be applying nimble, flexible intelligence to a demanding world — an ongoing focus of its curator, MIT faculty member Carlo Ratti.

The Biennale is the world’s most renowned exhibition of its kind, an international event whose subject matter shifts over time, with a new curator providing new focus every two years. This year, the Biennale’s formal theme is “Intelligens,” the Latin word behind “intelligence,” in English, and “intelligenza,” in Italian — a word that evokes both the exhibition’s international scope and the many ways humans learn, adapt, and create.

“Our title is ‘Intelligens. Natural, artificial, collective,’” notes Ratti, who is a professor of the practice of urban technologies and planning in the MIT School of Architecture and Planning. “One key point is how we can go beyond what people normally think about intelligence, whether in people or AI. In the built environment we deal with many types of feedback and need to leverage all types of intelligence to collect and use it all.”

That applies to the subject of climate change, as adaptation is an ongoing focal point for the design community, whether facing the need to rework structures or to develop new, resilient designs for cities and regions.

“I would emphasize how eager architects are today to play a big role in addressing the big crises we face on the planet we live in,” Ratti says. “Architecture is the only discipline to bring everybody together, because it means rethinking the built environment, the places we all live.”

He adds: “If you think about the fires in Los Angeles, or the floods in Valencia or Bangladesh, or the drought in Sicily, these are cases where architecture and design need to apply feedback and use intelligence.”

Not just sharing design, but creating it

The Venice Biennale is the leading event of its kind globally and one of the earliest: It started with art exhibitions in 1895 and later added biannual shows focused on other facets of culture. Since 1980, the Biennale of Architecture was held every two years, until the 2020 exhibition — curated by MIT’s Hashim Sarkis — was rescheduled to 2021 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It is now continuing in odd-numbered years.

After its May 10 opening, this year’s exhibition runs until Nov. 23.

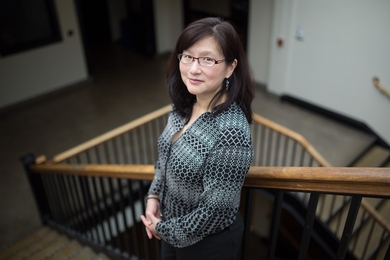

Ratti is a wide-ranging scholar, designer, and writer, and the long-running director of MIT’s Senseable City Lab, which has been on the leading edge of using data to understand cities as living systems.

Additionally, Ratti is a founding partner of the international design firm Carlo Ratti Associati. He graduated from the Politecnico di Torino and the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées in Paris, then earned his MPhil and PhD at Cambridge University. He has authored and co-authored hundeds of publications, including the books “Atlas of the Senseable City” (2023) and “The City of Tomorrow” (2016). Ratti’s work has been exhibited at the Venice Biennale, the Design Museum in Barcelona, the Science Museum in London, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, among other venues.

In his role as curator of this year’s Biennale, Ratti adapted the traditional format to engage with some of the leading questions design faces. Ratti and the organizers created multiple forums to gather feedback about the exhibition’s possibilities, sifting through responses during the planning process.

Ratti has also publicly called this year’s Biennale a “living lab,” not just an exhibition, in accordance with the idea of learning from feedback and developing designs in response.

Back in 1895, Ratti notes, the Biennale was principally “a place to share existing knowledge, with artists and architectures coming together every two years. Today, and for a few decades, you can find almost anything in architecture and art immediately online. I think Biennales can not only be places where you share existing knowledge, but places where you create new knowledge.”

At this moment, he emphasizes, that will often mean listening to nature as we grapple with climate solutions. It also implies recognizing that nature itself inevitably responds to inputs, too.

In this vein, Ratti says, “Remember what the great architect Carlo Scarpa once said: ‘Between a tree and a house, choose the tree.’ I see that as a powerful call to learn from nature — a vast lab of trial and error, guided by feedback loops. Too often in the 20th century, architects believed they had the solution and simply needed to scale it up. The results? Frequently disastrous. Especially now, when adaptability is everything, I believe in a different approach: experimentation, feedback, iteration. That’s the spirit I hope defines this year’s Biennale.”

An MIT touch

This year, MIT will again have a robust presence at the Biennale, even beyond Ratti’s presence as curator. In the first place, he emphasizes, there is a strong team organizing the Biennale. That includes MIT graduate student Claire Gorman, who has taken a year out of her studies to serve as principal assistant to the Biennale curator.

Many of the Biennale’s projects, Gorman observes, “align ecology, technology, and culture in stunning illustrations of the fact that intelligence emerges from the complex behaviors of many parts working together. Visitors to the exhibition will discover robots and artisans collaborating alongside algae, 3D printers, ancient building practices, and new materials. … One of the strengths of the exhibition is that it includes participants who approach similar topics from different points of view.”

Overall, Gorman adds, “Our hope is that visitors will come away from the exhibition with a sense of optimism about the capacity of design fields to unite many forms of expertise.”

Numerous other Institute faculty and researchers are represented as well. For instance, Daniela Rus, head of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab (CSAIL), has helped design an installation about using robotics in the restoration of ancient structures. And famed MIT computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee, creator of the World Wide Web, is participating in a Biennale event on intelligence.

“In choosing ‘Intelligens’ as the Venice Biennale theme, Carlo Ratti recognizes that our moment requires a holistic understanding of how different forms of intelligence — from social and ecological to computational and spatial — converge to shape our built environment,” Rus says. “The Biennale offers a timely platform to explore how architecture can mediate between these intelligences, creating buildings and cities that think with and for us.”

Even as the Biennale runs, there is also a separate exhibit in Venice showcasing MIT work in architecture and design. Running from May 10 through Nov. 23, at the Palazzo Diedo, the show, “The Next Earth: Computation, Crisis, Cosmology,” features the work of 40 faculty members in MIT’s Department of Architecture, along with entries from the think tank Antikythera.

Meanwhile, for the Biennale itself, the main exhibition hall, the Arsenale, is open, but other event spaces are being renovated. That means the organizers are using additional spaces in the city of Venice this year to showcase cutting-edge design work and installations.

“We’re turning Venice into a living lab — taking the Biennale beyond its usual borders,” Ratti says. “But there’s a bigger picture: Venice may be the world’s most fragile city, caught between rising seas and the crush of mass tourism. That’s why it could become a true laboratory for the future. Venice today could be a glimpse of the world tomorrow.”