Humans know they exist, but how does “knowing” work? Despite all that’s been learned about brain function and the bodily processes it governs, we still don't understand where the subjective experiences associated with brain functions originate.

A new interdisciplinary project seeks to find answers to these kinds of big questions around consciousness, a fundamental yet elusive phenomenon.

The MIT Consciousness Club is co-led by philosopher Matthias Michel, the Old Dominion Career Development Professor in the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, and Earl Miller, the Picower Professor of Neuroscience in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

Funded by a grant from the MIT Human Insight Collaborative’s (MITHIC) SHASS+ Connectivity Fund, the MIT Consciousness Club aims to build a bridge between philosophy and cognitive (neuro)science, while also engaging the Boston area’s academic community to advance consciousness research.

“It’s possible to study this scientifically,” says Michel. “MIT positioning itself as a leader in the field would change everything.”

“Matthias takes a science-based approach to the work” Miller adds. “A coherent, fact-based, research-supported understanding of and approach to consciousness can have a massive impact on our approach to public health.”

Working together, they hope to increase access to a diverse network of researchers, improve their understanding of how consciousness works, and develop tools to measure consciousness objectively.

The MIT Consciousness Club plans to hold monthly events featuring expert talks and Q&A sessions collaborating on topics like the neural correlates of consciousness, unconscious perception, and consciousness in animals and AI systems.

“What can science tell us about brain function and consciousness?” Michel asks. “Why does neurological activity give rise to conscious experience, as opposed to nothing?”

“Cognition is your brain self-organizing,” Miller adds. “How does the brain organize itself to attain goals?” Unlike amoebae, Miller notes, humans both react to and act on the environment.

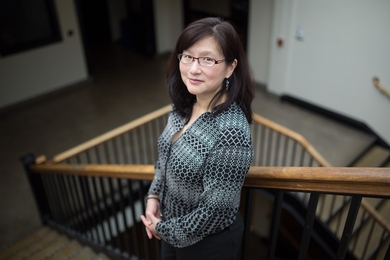

Michel’s research focuses on the philosophy of cognitive science, mind, and perception, with interests in the philosophy of measurement and philosophy of psychiatry. Most of his recent work focuses on methodological and foundational issues in the scientific study of consciousness.

Miller studies the neural basis of memory and cognition. His areas of focus include the neural mechanisms of attention, learning, and memory needed for voluntary, goal-directed behavior, with a special focus on the brain’s prefrontal cortex.

“I was engaged with how the mind works”

Before arriving at MIT in 2024, Michel’s academic and research interests led him to his work at the intersection of neuroscience and philosophy. “I was engaged with how the mind works,” he says. He describes a course of study focused on issues related to logic and reasoning and the ways the brain toggles between conscious and unconscious brain function.

Following the completion of his doctoral and postdoctoral studies, he continued his investigation into the nature of consciousness. Work from Melvyn Goodale at Western University led to a light-bulb moment for him.

“According to Goodale, the brain operates with two visual systems — conscious and non-conscious — responsible for fine-grained motor commands,” he says. “Researchers discovered the way someone adjusts their grip, for example, is based on a non-conscious stream of vision.”

This discovery helped further Michel’s commitment to understanding consciousness’s function objectively. “How long does it take a person to become conscious of something?” he asks. “There is a lag between when a signal is presented and when we get to subjectively experience it.” Measuring that delay, and understanding the path from stimulus to signal processing and response, is a core facet of Michel’s investigation. Consciousness, he asserts, is for planning, not reacting.

Michel and Miller aren’t only interested in human brains. Improved understanding of animal and other living things’ consciousness are also under discussion. “How do you organize states of consciousness in nonhuman species?” Michel asks. Understanding how species interact with the world can help us understand it and them better.

Making room for investigation and collaboration

One of the surprising discoveries both uncovered while shaping the idea that would become the MIT Consciousness Club is the size of the group interested in participating. “It’s larger than I thought,” Miller says. “We’ve established connections with colleagues at the Lincoln Laboratory and Northeastern University, all of whom are invested in studying consciousness.”

Both Michel and Miller believe researchers at MIT and elsewhere can benefit from the kind of collaboration MITHIC funding makes possible. “The goal is to create community,” Michel says, “while also improving the research area’s reputation.”

“It’s possible to study consciousness scientifically because of its connection to other questions,” Miller adds.

The investigative avenues available when you can explore ideas for their own sake — like how consciousness functions, for example — can lead to exciting breakthroughs. “Imagine if consciousness research became a focus area, rather than a sideline, for people interested in its study,” Michel says.

“You can’t study the complexities of executive [brain] function and not get to consciousness,” Miller continues. “Designing a system to effectively and accurately measure consciousness levels in the brain has a variety of potentially groundbreaking applications.”

Miller works with Emery Brown, the Edward Hood Taplin Professor of Medical Engineering and Computational Neuroscience at MIT and a practicing anesthesiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital for whom consciousness is a central concern.

“General anesthesia during surgical procedures is bad when you’re really young or really old,” Miller says. “Older people who need anesthesia can experience cognitive decline, which is why health-care providers are often reluctant to perform surgeries despite needing it.” A better understanding of the mechanisms that create consciousness can help improve pre- and post-surgical care delivery and outcomes.

Researching consciousness can also yield substantial public health benefits, including more-efficient mental health treatment. “Mental health disorders affect high-level cognitive function,” Miller continues. “Anesthesia interacts with drugs used to treat mental health disorders, which can severely impact patient care.” Each of the researchers wants to understand how drug therapies actually mediate patient experiences.

Ultimately, the professors agree that improved access to consciousness studies will improve research rigor and help burnish the field’s reputation.