Ernest Opoku knew he wanted to become a scientist when he was a little boy. But his school in Dadease, a small town in Ghana, offered no elective science courses — so Opoku created one for himself.

Even though they had neither a dedicated science classroom nor a lab, Opoku convinced his principal to bring in someone to teach him and five other friends he had convinced to join him. With just a chalkboard and some imagination, they learned about chemical interactions through the formulas and diagrams they drew together.

“I grew up in a town where it was difficult to find a scientist,” he says.

Today, Opoku has become one himself, recently earning a PhD in quantum chemistry from Auburn University. This year, he joins MIT as a part of the School of Science Dean’s Postdoctoral Fellowship program. Working with the Van Voorhis Group at the Department of Chemistry, Opoku’s goal is to advance computational methods to study how electrons behave — a fundamental research that underlies applications ranging from materials science to drug discovery.

“As a boy who wanted to satisfy my own curiosities at a young age, in addition to the fact that my parents had minimal formal education,” Opoku says, “I knew that the only way I would be able to accomplish my goal was to work hard.”

In pursuit of knowledge

When Opoku was 8 years old, he began independently learning English at school. He would come back with homework, but his parents were unable to help him, as neither of them could read or write in English. Frustrated, his mother asked an older student to help tutor her son.

Every day, the boys would meet at 6 o’clock. With no electricity at either of their homes, they practiced new vocabulary and pronunciations together by a kerosene lamp.

As he entered junior high school, Opoku’s fascination with nature grew.

“I realized that chemistry was the central science that really offered the insight that I wanted to really understand Creation from the smallest level,” he says.

He studied diligently and was able to get into one of Ghana’s top high schools — but his parents couldn’t afford the tuition. He therefore enrolled in Dadease Agric Senior High School in his hometown. By growing tomatoes and maize, he saved up enough money to support his education.

In 2012, he got into Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), a first-ranking university in Ghana and the West Africa region. There, he was introduced to computational chemistry. Unlike many other branches of science, the field required only a laptop and the internet to study chemical reactions.

“Anything that comes to mind, anytime I can grab my computer and I’ll start exploring my curiosity. I don’t have to wait to go to the laboratory in order to interrogate nature,” he says.

Opoku worked from early morning to late night. None of it felt like work, though, thanks to his supervisor, the late quantum chemist Richard Tia, who was an associate professor of chemistry at KNUST.

“Every single day was a fun day,” he recalls of his time working with Tia. “I was being asked to do the things that I myself wanted to know, to satisfy my own curiosity, and by doing that I’ll be given a degree.”

In 2020, Opoku’s curiosity brought him even further, this time overseas to Auburn University in Alabama for his PhD. Under the guidance of his advisor, Professor J. V. Ortiz, Opoku contributed to the development of new computational methods to simulate how electrons bind to or detach from molecules, a process known as electron propagation.

What is new about Opoku’s approach is that it does not rely on any adjustable or empirical parameters. Unlike some earlier computational methods that require tuning to match experimental results, his technique uses advanced mathematical formulations to directly account for first principles of electron interactions. This makes the method more accurate — closely resembling results from lab experiments — while using less computational power.

By streamlining the calculations and eliminating guesswork, Opoku’s work marks a major step toward faster, more trustworthy quantum simulations across a wide range of molecules, including those never studied before — laying the groundwork for breakthroughs in many areas such as materials science and sustainable energy.

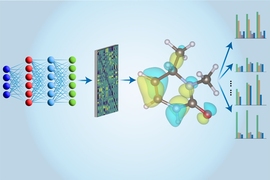

For his postdoctoral research at MIT, Opoku aims to advance electron propagator methods to address larger and more complex molecules and materials by integrating quantum computing, machine learning, and bootstrap embedding — a technique that simplifies quantum chemistry calculations by dividing large molecules into smaller, overlapping fragments. He is collaborating with Troy Van Voorhis, the Haslam and Dewey Professor of Chemistry, whose expertise in these areas can help make Opoku’s advanced simulations more computationally efficient and scalable.

“His approach is different from any of the ways that we've pursued in the group in the past,” Van Voorhis says.

Passing along the opportunity to learn

Opoku thanks previous mentors who helped him overcome the “intellectual overhead required to make contributions to the field,” and believes Van Voorhis will offer the same kind of support.

In 2021, Opoku joined the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers (NOBCChE) to gain mentorship, networking, and career development opportunities within a supportive community. He later led the Auburn University chapter as president, helping coordinate k-12 outreach to inspire the next generation of scientists, engineers, and innovators.

“Opoku’s mentorship goes above and beyond what would be typical at his career stage,” says Van Voorhis. “One reason is his ability to communicate science to people, and not just the concepts of science, but also the process of science."

Back home, Opoku founded the Nesvard Institute of Molecular Sciences to support African students to develop not only skills for graduate school and professional careers, but also a sense of confidence and cultural identity. Through the nonprofit, he has mentored 29 students so far, passing along the opportunity for them to follow their curiosity and help others do the same.

“There are many areas of science and engineering to which Africans have made significant contributions, but these contributions are often not recognized, celebrated, or documented,” Opoku says.

He adds: “We have a duty to change the narrative.”