Audio

Traditional folk ballads are one of our most enduring forms of cultural expression. They can also be lost to society, forgotten over time. That’s why, in the mid-1700s, when a Scottish woman named Anna Gordon was found to know three dozen ancient ballads, collectors tried to document all of these songs — a volume of work that became a kind of sensation in its time, a celebrated piece of cultural heritage.

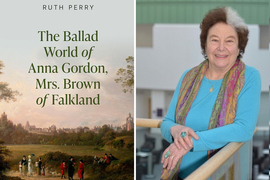

That story is told in MIT Professor Emerita Ruth Perry’s latest book, “The Ballad World of Anna Gordon, Mrs. Brown of Falkland,” published this year by Oxford University Press. In it, Perry details what we know about the ways folk ballads were created and transmitted; how Anna Gordon came to know so many; the social and political climate in which they existed; and why these songs meant so much in Scotland and elsewhere in the Atlantic world. Indeed, Scottish immigrants brought their music to the U.S., among other places.

MIT News sat down with Perry, who is MIT’s Ann Fetter Friedlaender Professor of Humanities, Emerita, to talk about the book.

Q: This is fascinating topic with a lot of threads woven together. To you, what is the book about?

A: It’s really three books. It’s a book about Anna Gordon and her family, a very interesting middle-class family living in Aberdeen in the middle of the 18th century. And it’s a book about balladry and what a ballad is — a story told in song, and ballads are the oldest known poetry in English. Some of them are gorgeous. Third, it’s a book about the relationship between Scotland and England, the effects of the Jacobite uprising in 1745, social attitudes, how people lived, what they ate, education — it’s very much about 18th century Scotland.

Q: Okay, who was Anna Gordon, and what was her family milieu?

A: Anna’s father, Thomas Gordon, was a professor at King’s College, now the University of Aberdeen. He was a professor of humanity, which in those days meant Greek and Latin, and was well-connected to the intellectual community of the Scottish Enlightenment. A friend of his, an Edinburgh writer, lawyer, and judge, William Tytler, who heard cases all over the country and always stayed with Thomas Gordon and his family when he came to Aberdeen, was intensely interested in Scottish traditional music. He found out that Anna Gordon had learned all these ballads as a child, from her mother and aunt and some servants. Tytler asked if she would write them down, both tunes and words.

That was the earliest manuscript of ballads ever collected from a named person in Scotland. Once it was in existence, all kinds of people wanted to see it; it got spread throughout the country. In my book, I detail much of the excitement over this manuscript.

The thing about Anna’s ballads is: It’s not just that there are more of them, and more complete versions that are fuller, with more verses. They’re more beautiful. The language is more archaic, and there are marvelous touches. It is thought, and I agree, that Anna Gordon was an oral poet. As she remembered ballads and reproduced them, she improved on them. She had a great memory for the best bits and would improve other parts.

Q: How did it come about that at this time, a woman such as Anna Gordon would be the keeper and creator of cultural knowledge?

A: Women were more literate in Scotland than elsewhere. The Scottish Parliament passed an act in 1695 requiring every parish in the Church of Scotland to have not only a minister, but a teacher. Scotland was the most literate country in Europe in the 18th century. And those parish schoolmasters taught local kids. The parents did have to pay a few pennies for their classes, and, true, more parents paid for sons than for daughters. But there were daughters who took classes. And there were no opportunities like this in England at the time. Education was better for women in Scotland. So was their legal position, under common law in Scotland. When the Act of Union was formed in 1707, Scotland retained its own legal system, which had more extensive rights for women than in England.

Q: I know it’s complex, but generally, why was this?

A: Scotland was a much more democratic country, culture, and society than England, period. When Elizabeth I died in 1603, the person who inherited the throne was the King of Scotland James VI, who went to England with his court — which included the Scottish aristocracy. So, the Scottish aristocracy ended up in London. I’m sure they went back to their hunting lodges for the hunting season, but they didn’t live there [in Scotland] and they didn’t set the tone of the country. It was democratized because all that was left were a lot of lawyers and ministers and teachers.

Q: What is distinctive about the ballads in this corpus of songs Anna Gordon knew and documented?

A: A common word about ballads is that there’s a high body count, and they’re all about people dying and killing each other. But that is not true of Anna Gordon’s ballads. They’re about younger women triumphing in the world, often against older women, which is interesting, and even more often against fathers. The ballads are about family discord, inheritance, love, fidelity, lack of fidelity, betrayal. There are ballads about fighting and bloodshed, but not so many. They’re about the human condition. And they have interesting qualities because they’re oral poetry, composed and remembered and changed and transmitted from mouth to ear and not written down. There are repetitions and parallelisms, and other hallmarks of oral poetry. The sort of thing you learned when you read Homer.

Q: So is this a form of culture generated in opposition to those controlling society? Or at least, one that’s popular regardless of what some elites thought?

A: It is in Scotland, because of the enmity between Scotland and England. We’re talking about the period of Great Britain when England is trying to gobble up Scotland and some Scottish folks don’t want that. They want to retain their Scottishness. And the ballad was a Scottish tradition that was not influenced by England. That’s one reason balladry was so important in 18th-century Scotland. Everybody was into balladry partly because it was a unique part of Scottish culture.

Q: To that point, it seems like an unexpected convergence, for the time, to see a more middle-class woman like Anna Gordon transmitting ballads that had often been created and sung by people of all classes.

A: Yes. At first I thought I was just working on a biography of Anna Gordon. But it’s fascinating how the culture was transmitted, how intellectually rich that society was, how much there is to examine in Scottish culture and society of the 18th century. Today people may watch “Outlander,” but they still wouldn’t know anything about this!