It’s no question that graduate school in fundamental research was never for the faint of heart, but academia’s nationwide funding disruptions threaten not just research happening now, but the critical pipeline for the next generation of scientists.

“What’s keeping me up at night is the uncertainty,” says MIT Institute Professor and Nobel laureate Phillip A. Sharp, who is also professor of biology emeritus and intramural faculty at the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research.

In the short term, Sharp foresees challenges in sustaining students so they can complete their degrees, postdocs to finish their professional preparation, and faculty to set up and sustain their labs. In the long term, the impact becomes potentially existential — fewer people pursuing academia now means fewer advancements in the decades to come.

So, when Sharp was looped into discussions about a gift in his honor, he knew exactly where it should be directed. Established this year thanks to a generous donation from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, the Phil Sharp-Alnylam Fund for Emerging Scientists will support graduate students and faculty within life sciences.

“This generosity by Alnylam provides an opportunity to bridge the uncertainty and ideally create the environment where students and others will feel that it’s possible to do science and have a career,” Sharp says.

The fund is set up to be flexible, so the expendable gift can be used to address the evolving needs of the Department of Biology, including financial support, research grants, and seed funding.

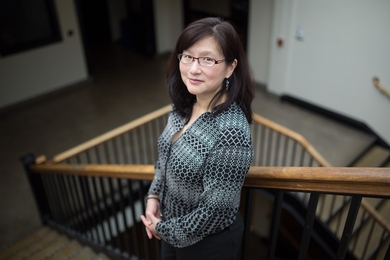

“This fund will help us fortify the department’s capacity to train new generations of life science innovators and leaders,” says department head Amy E. Keating, the Jay A. Stein (1968) Professor of Biology and professor of biological engineering. “It is a great privilege for the department to be part of this recognition of Phil’s key role at Alnylam.”

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, a company Sharp co-founded in 2002, is, in fact, a case study for the type of long-term investment in fundamental discovery that leads to paradigm-shifting strides in biomedical science, such as: What if the genetic drivers of diseases could be silenced by harnessing a naturally occurring gene regulation process?

Good things take time

In 1998, Andrew Fire PhD ’83, who was trained as a graduate student in the Sharp Lab at MIT, and Craig Mello published a paper showing that double-stranded RNA suppresses the expression of the protein from the gene that encodes its sequence. The process, known as RNA interference, was such a groundbreaking revelation that Fire and Mello shared a Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology less than a decade later.

RNAi is an innate cellular gene regulation process that can, for example, assist cells in defending against viruses by degrading viral RNA, thereby interfering with the production of viral proteins. Taking advantage of this natural process to fine-tune the expression of genes that encode specific proteins was a promising option for disease treatment, as many diseases are caused by the creation or buildup of mutated or faulty proteins. This approach would address the root cause of the disease, rather than its downstream symptoms.

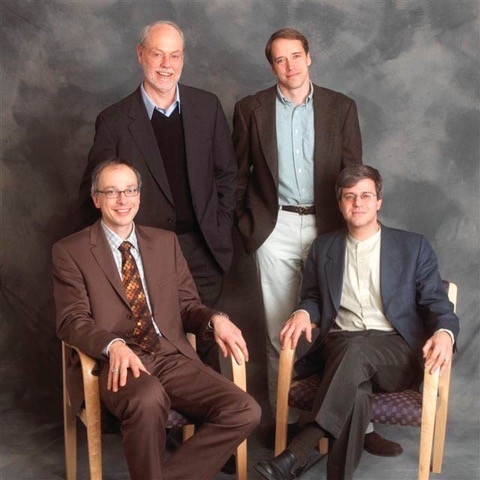

The details of the biochemistry of RNAi were characterized and patented, and in 2002, Alnylam was founded by Sharp, David Bartel, Paul Schimmel PhD ’67, Thomas Tuschl, and Phillip Zamore SM ’86.

“Sixteen years later, we got our first approval for a totally novel therapeutic agent to treat disease,” Sharp says. “Something in a research laboratory, translated in about as short a time as you can do, gave rise to this whole new way of treating critical diseases.”

This timeline isn’t atypical. Particularly in health care, Sharp notes, investments often occur five or 10 years before they come to fruition.

“Phil Sharp’s visionary idea of harnessing RNAi to treat disease brought brilliant people together to pioneer this new class of medicines. RNAi therapeutics would not exist without the bridge Phil built between academia and industry. Now there are six approved Alnylam-discovered RNAi therapeutics, and we are exploring potential treatments for a range of rare and prevalent diseases to improve the lives of many more patients in need,” says Kevin Fitzgerald, chief scientific officer of Alnylam Pharmaceuticals.

Today, the company has grown to over 2,500 employees, markets its six approved treatments worldwide, and has a long list of research programs that are likely to yield new therapeutic agents in the years to come.

Change is always on the horizon

Sharp foresees potential benefits for companies that contribute to academia, in the way Alnylam Pharmaceuticals has through the Phil Sharp-Alnylam Fund for Emerging Scientists.

“We are proud to support the MIT Department of Biology because investments in both early-stage and high-risk research have the potential to unlock the next wave of medical breakthroughs to help so many patients waiting for hope throughout the world,” says Yvonne Greenstreet, CEO of Alnylam Pharmaceuticals.

It is prudent for industry to keep its finger on the pulse — for becoming aware of new talent and for anticipating landscape-shifting advancements, such as artificial intelligence. Sharp notes that academia, in its pursuit of fundamental knowledge, “creates new ideas, new opportunities, and new ways of doing things.”

“All of society, including biotech, is anticipating that AI is going to be a great accelerator,” Sharp says. “Being associated with institutions that have great biology, chemistry, neuroscience, engineering, and computational innovation is how you sort through this anticipation of what the future is going to be.”

But, Sharp says, it’s a two-way street: Academia should also be asking how it can best support the future workplaces for their students who will go on to have careers in industry. To that end, the Department of Biology recently launched a career connections initiative for current trainees to draw on the guidance and experience of alums, and to learn how to hone their knowledge so that they are a value-add to industry’s needs.

“The symbiotic nature of these relationships is healthy for the country, and for society, all the way from basic research through innovative companies of all sizes, health-care delivery, hospitals, and right down to primary care physicians meeting one-on-one with patients,” Sharp says. “We’re all part of that, and unless all parts of it remain healthy and appreciated, it will bode poorly for the future of the country’s economy and well-being.”