When people think about fiber optic cables, its usually about how they’re used for telecommunications and accessing the internet. But fiber optic cables — strands of glass or plastic that allow for the transmission of light — can be used for another purpose: imaging the ground beneath our feet.

MIT Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) PhD student Hilary Chang recently used the MIT fiber optic cable network to successfully image the ground underneath campus using a method known as distributed acoustic sensing (DAS). By using existing infrastructure, DAS can be an efficient and effective way to understand ground composition, a critical component for assessing the seismic hazard of areas, or how at risk they are from earthquake damage.

“We were able to extract very nice, coherent waves from the surroundings, and then use that to get some information about the subsurface,” says Chang, the lead author of a recent paper describing her work that was co-authored with EAPS Principal Research Scientist Nori Nakata.

Dark fibers

The MIT campus fiber optic system, installed from 2000 to 2003, services internal data transport between labs and buildings as well as external transport, such as the campus internet (MITNet). There are three major cable hubs on campus from which lines branch out into buildings and underground, much like a spiderweb.

The network allocates a certain number of strands per building, some of which are “dark fibers,” or cables that are not actively transporting information. Each campus fiber hub has redundant backbone cables between them so that, in the event of a failure, network transmission can switch to the dark fibers without loss of network services.

DAS can use existing telecommunication cables and ambient wavefields to extract information about the materials they pass through, making it a valuable tool for places like cities or the ocean floor, where conventional sensors can’t be deployed. Chang, who studies earthquake waveforms and the information we can extract from them, decided to try it out on the MIT campus.

In order to get access to the fiber optic network for the experiment, Chang reached out to John Morgante, a manager of infrastructure project engineering with MIT Information Systems and Technology (IS&T). Morgante has been at MIT since 1998 and was involved with the original project installing the fiber optic network, and was thus able to provide personal insight into selecting a route.

“It was interesting to listen to what they were trying to accomplish with the testing,” says Morgante. While IS&T has worked with students before on various projects involving the school’s network, he said that “in the physical plant area, this is the first that I can remember that we’ve actually collaborated on an experiment together.”

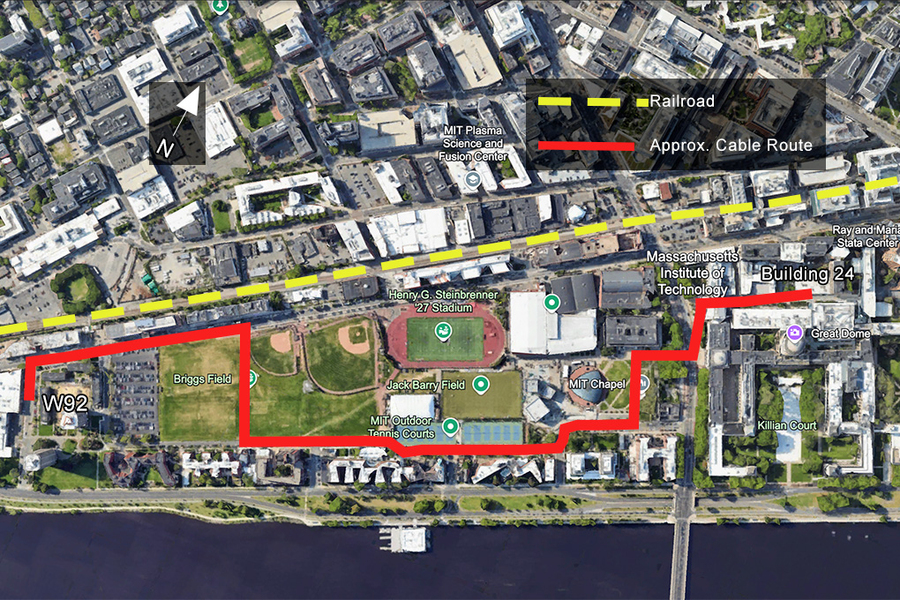

They decided on a path starting from a hub in Building 24, because it was the longest running path that was entirely underground; above-ground wires that cut through buildings wouldn’t work because they weren’t grounded, and thus were useless for the experiment. The path ran from east to west, beginning in Building 24, traveling under a section of Massachusetts Ave., along parts of Amherst and Vassar streets, and ending at Building W92.

“[Morgante] was really helpful,” says Chang, describing it as “a very good experience working with the campus IT team.”

Locating the cables

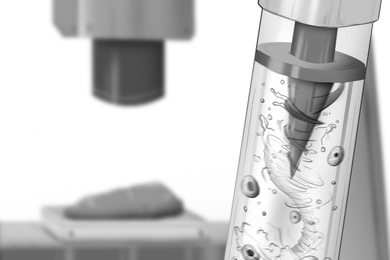

After renting an interrogator, a device that sends laser pulses to sense ambient vibrations along the fiber optic cables, Chang and a group of volunteers were given special access to connect it to the hub in Building 24. They let it run for five days.

To validate the route and make sure that the interrogator was working, Chang conducted a tap test, in which she hit the ground with a hammer several times to record the precise GPS coordinates of the cable. Conveniently, the underground route is marked by maintenance hole covers that serve as good locations to do the test. And, because she needed the environment to be as quiet as possible to collect clean data, she had to do it around 2 a.m.

“I was hitting it next to a dorm and someone yelled ‘shut up,’ probably because the hammer blows woke them up,” Chang recalls. “I was sorry.” Thankfully, she only had to tap at a few spots and could interpolate the locations for the rest.

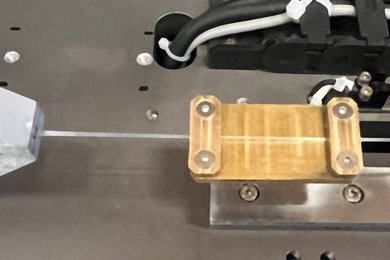

During the day, Chang and her fellow students — Denzel Segbefia, Congcong Yuan, and Jared Bryan — performed an additional test with geophones, another instrument that detects seismic waves, out on Brigg’s Field where the cable passed under it to compare the signals. It was an enjoyable experience for Chang; when the data were collected in 2022, the campus was coming out of pandemic measures, with remote classes sometimes still in place. “It was very nice to have everyone on the field and do something with their hands,” she says.

The noise around us

Once Chang collected the data, she was able to see plenty of environmental activity in the waveforms, including the passing of cars, bikes, and even when the train that runs along the northern edge of campus made its nightly passes.

After identifying the noise sources, Chang and Nakata extracted coherent surface waves from the ambient noises and used the wave speeds associated with different frequencies to understand the properties of the ground the cables passed through. Stiffer materials allow fast velocities, while softer material slows it.

“We found out that the MIT campus is built on soft materials overlaying a relatively hard bedrock,” Chang says, which confirms previously known, albeit lower-resolution, information about the geology of the area that had been collected using seismometers.

Information like this is critical for regions that are susceptible to destructive earthquakes and other seismic hazards, including the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, which has experienced earthquakes as recently as this past week. Areas of Boston and Cambridge characterized by artificial fill during rapid urbanization are especially at risk due to its subsurface structure being more likely to amplify seismic frequencies and damage buildings. This non-intrusive method for site characterization can help ensure that buildings meet code for the correct seismic hazard level.

“Destructive seismic events do happen, and we need to be prepared,” she says.