Within the human brain, a network of regions has evolved to process language. These regions are consistently activated whenever people listen to their native language or any language in which they are proficient.

A new study by MIT researchers finds that this network also responds to languages that are completely invented, such as Esperanto, which was created in the late 1800s as a way to promote international communication, and even to languages made up for television shows such as “Star Trek” and “Game of Thrones.”

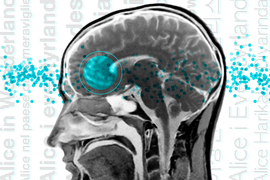

To study how the brain responds to these artificial languages, MIT neuroscientists convened nearly 50 speakers of these languages over a single weekend. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the researchers found that when participants listened to a constructed language in which they were proficient, the same brain regions lit up as those activated when they processed their native language.

“We find that constructed languages very much recruit the same system as natural languages, which suggests that the key feature that is necessary to engage the system may have to do with the kinds of meanings that both kinds of languages can express,” says Evelina Fedorenko, an associate professor of neuroscience at MIT, a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the senior author of the study.

The findings help to define some of the key properties of language, the researchers say, and suggest that it’s not necessary for languages to have naturally evolved over a long period of time or to have a large number of speakers.

“It helps us narrow down this question of what a language is, and do it empirically, by testing how our brain responds to stimuli that might or might not be language-like,” says Saima Malik-Moraleda, an MIT postdoc and the lead author of the paper, which appears this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Convening the conlang community

Unlike natural languages, which evolve within communities and are shaped over time, constructed languages, or “conlangs,” are typically created by one person who decides what sounds will be used, how to label different concepts, and what the grammatical rules are.

Esperanto, the most widely spoken conlang, was created in 1887 by L.L. Zamenhof, who intended it to be used as a universal language for international communication. Currently, it is estimated that around 60,000 people worldwide are proficient in Esperanto.

In previous work, Fedorenko and her students have found that computer programming languages, such as Python — another type of invented language — do not activate the brain network that is used to process natural language. Instead, people who read computer code rely on the so-called multiple demand network, a brain system that is often recruited for difficult cognitive tasks.

Fedorenko and others have also investigated how the brain responds to other stimuli that share features with language, including music and nonverbal communication such as gestures and facial expressions.

“We spent a lot of time looking at all these various kinds of stimuli, finding again and again that none of them engage the language-processing mechanisms,” Fedorenko says. “So then the question becomes, what is it that natural languages have that none of those other systems do?”

That led the researchers to wonder if artificial languages like Esperanto would be processed more like programming languages or more like natural languages. Similar to programming languages, constructed languages are created by an individual for a specific purpose, without natural evolution within a community. However, unlike programming languages, both conlangs and natural languages can be used to convey meanings about the state of the external world or the speaker’s internal state.

To explore how the brain processes conlangs, the researchers invited speakers of Esperanto and several other constructed languages to MIT for a weekend conference in November 2022. The other languages included Klingon (from “Star Trek”), Na’vi (from “Avatar”), and two languages from “Game of Thrones” (High Valyrian and Dothraki). For all of these languages, there are texts available for people who want to learn the language, and for Esperanto, Klingon, and High Valyrian, there is even a Duolingo app available.

“It was a really fun event where all the communities came to participate, and over a weekend, we collected all the data,” says Malik-Moraleda, who co-led the data collection effort with former MIT postbac Maya Taliaferro, now a PhD student at New York University.

During that event, which also featured talks from several of the conlang creators, the researchers used fMRI to scan 44 conlang speakers as they listened to sentences from the constructed language in which they were proficient. The creators of these languages — who are co-authors on the paper — helped construct the sentences that were presented to the participants.

While in the scanner, the participants also either listened to or read sentences in their native language, and performed some nonlinguistic tasks for comparison. The researchers found that when people listened to a conlang, the same language regions in the brain were activated as when they listened to their native language.

Common features

The findings help to identify some of the key features that are necessary to recruit the brain’s language processing areas, the researchers say. One of the main characteristics driving language responses seems to be the ability to convey meanings about the interior and exterior world — a trait that is shared by natural and constructed languages, but not programming languages.

“All of the languages, both natural and constructed, express meanings related to inner and outer worlds. They refer to objects in the world, to properties of objects, to events,” Fedorenko says. “Whereas programming languages are much more similar to math. A programming language is a symbolic generative system that allows you to express complex meanings, but it’s a self-contained system: The meanings are highly abstract and mostly relational, and not connected to the real world that we experience.”

Some other characteristics of natural languages, which are not shared by constructed languages, don’t seem to be necessary to generate a response in the language network.

“It doesn’t matter whether the language is created and shaped over time by a community of speakers, because these constructed languages are not,” Malik-Moraleda says. “It doesn’t matter how old they are, because conlangs that are just a decade old engage the same brain regions as natural languages that have been around for many hundreds of years.”

To further refine the features of language that activate the brain’s language network, Fedorenko’s lab is now planning to study how the brain responds to a conlang called Lojban, which was created by the Logical Language Group in the 1990s and was designed to prevent ambiguity of meanings and promote more efficient communication.

The research was funded by MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, Brain and Cognitive Sciences Department, the Simons Center for the Social Brain, the Frederick A. and Carole J. Middleton Career Development Professorship, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health.