Give Dwai Banerjee credit: He doesn’t pick easy topics to study.

Banerjee is an MIT scholar who in a short time has produced a wide-ranging body of work about the impact of technology on society — and who, as a trained anthropologist, has a keen eye for people’s lived experience.

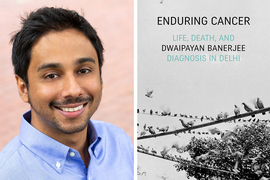

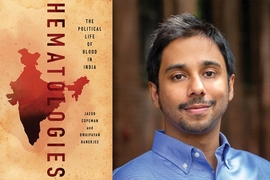

In one book, “Enduring Cancer,” from 2020, Banerjee studies the lives of mostly poor cancer patients in Delhi, digging into their psychological horizons and interactions with the world of medical care. Another book, “Hematologies,” also from 2020, co-authored with anthropologist Jacob Copeman, examines common ideas about blood in Indian society.

And in still another book, forthcoming later this year, Banerjee explores the history of computing in India — including the attempt by some to generate growth through domestic advances, even as global computer firms were putting the industry on rather different footing.

“I enjoy having the freedom to explore new topics,” says Banerjee, an associate professor in MIT’s Program in Science, Technology, and Society (STS). “For some people, building on their previous work is best, but I need new ideas to keep me going. For me, that feels more natural. You get invested in a subject for a time and try to get everything out of it.”

What largely links these disparate topics together is that Banerjee, in his work, is a people person: He aims to illuminate the lives and thoughts of everyday citizens as they interact with the technologies and systems of contemporary society.

After all, a cancer diagnosis can be life-changing not just in physical terms, but psychologically. For some, having cancer creates “a sense of being unmoored from prior certainties about oneself and one’s place in the world,” as Banerjee writes in “Enduring Cancer.”

The technology that enables diagnoses does not meet all our human needs, so the book traces the complicated inner lives of patients, and a medical system shifting to meet psychological and palliative-care challenges. Technology and society interact beyond blockbuster products, as the book deftly implies.

For his research and teaching, Banerjee was awarded tenure at MIT last year.

Falling for the humanities

Banerjee grew up in Delhi, and as a university student he expected to work in computing, before changing course.

“I was going to go to graduate school for computer engineering,” Banerjee says. “Then I just fell in love with the humanities, and studied the humanities and social sciences.” He received an MPhil and an MA in sociology from the Delhi School of Economics, then enrolled as a PhD student at New York University.

At NYU, Banerjee undertook doctoral studies in cultural anthropology, while performing some of the fieldwork that formed the basis of “Enduring Cancer.” At the same time, he found the people he was studying were surrounded by history — shaping the technologies and policies they encountered, and shaping their own thought. Ultimately even Banerjee’s anthropological work has a strong historical dimension.

After earning his PhD, Banerjee became a Mellon Fellow in the Humanities at Dartmouth College, then joined the MIT faculty in STS. It is a logical home for someone who thinks broadly and uses multiple research methods, from the field to the archives.

“I sometimes wonder if I am an anthropologist or if I am an historian,” Banerjee allows. “But it is an interdisciplinary program, so I try to make the most of that.”

Indeed, the STS program draws on many fields and methods, with its scholars and students linked by a desire to rigorously examine the factors shaping the development and application of technology — and, if necessary, to initiate difficult discussions about technology’s effects.

“That’s the history of the field and the department at MIT, that it’s a kind of moral backbone,” Banerjee says.

Finding inspiration

As for where Banerjee’s book ideas come from, he is not simply looking for large issues to write about, but things that spark his intellectual and moral sensibilities — like disadvantaged cancer patients in Delhi.

“‘Enduring Cancer,’ in my mind, is a sort of a traditional medical anthropology text, which came out of finding inspiration from these people, and running with it as far as I could,” Banerjee says.

Alternately, “‘Hematologies’ came out of a collaboration, a conversation with Jacob Copeman, with us talking about things and getting excited about it,” Banerjee adds. “The intellectual friendship became a driving force.” Copeman is now an anthropologist on the faculty at the University of Santiago de Compostela, in Spain.

As for Banerjee’s forthcoming book about computing in India, the spark was partly his own remembered enjoyment of seeing the internet reach the country, facilitated though it was by spotty dial-up modems and other now-quaint-seeming tools.

“It’s coming from an old obsession,” Banerjee says. “When the internet had just arrived, at that time when something was just blowing up, it was exciting. This project is [partly about] recovering my early enjoyment of what was then a really exciting time.”

The subject of the book itself, however, predates the commercial internet. Rather, Banerjee chronicles the history of computing during India’s first few decades after achieving independence from Britain, in 1947. Even into the 1970s, India’s government was interested in creating a strong national IT sector, designing and manufacturing its own machines. Eventually those efforts faded, and the multinational computing giants took ahold of India’s markets.

The book details how and why this happened, in the process recasting what we think we know about India and technology. Today, Banerjee notes, India is an exporter of skilled technology talent and an importer of tech tools, but that wasn’t predestined. It is more that the idea of an autonomous tech sector in the country ran into the prevailing forces of globalization.

“The book traces this moment of this high confidence in the country’s ability to do these things, producing manufacturing and jobs and economic growth, and then it traces the decline of that vision,” Banerjee says.

“One of the aims is for it to be a book anyone can read,” Banerjee adds. In that sense, the principle guiding his interests is now guiding his scholarly output: People first.