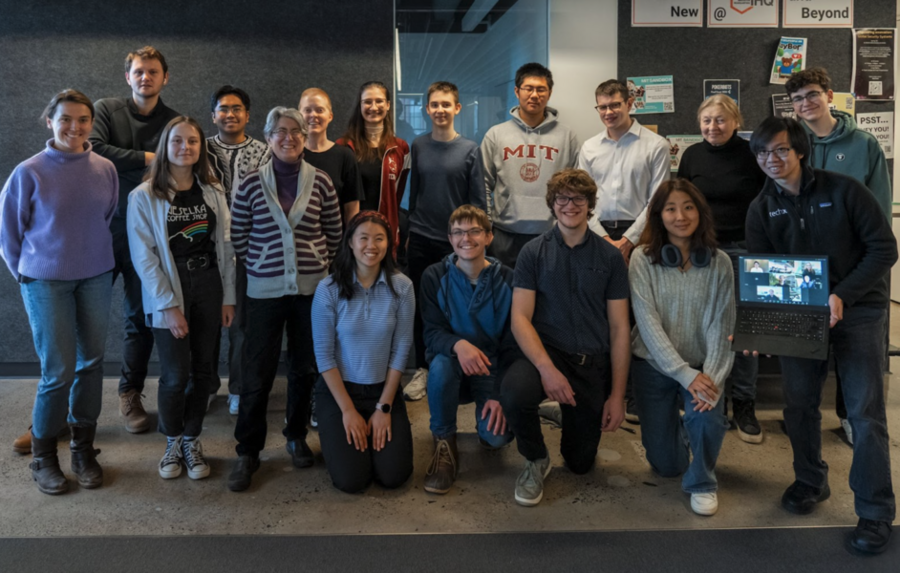

“No cash prizes. But our friends in Kyiv are calling in, and they’ll probably say thanks,” was the the tagline that drew students and tech professionals to join MIT-Ukraine’s first-ever hackathon this past January.

The hackathon was co-sponsored by MIT-Ukraine and Mission Innovation X and was shaped by the efforts of MIT alumni from across the world. It was led by Hosea Siu ’14, SM ’15, PhD ’18, a seasoned hackathon organizer and AI researcher, in collaboration with Phil Tinn MCP ’16, a research engineer now based at SINTEF [Foundation for Industrial and Technical Research] in Norway. The program was designed to prioritize tangible impact:

“In a typical hackathon, you might get a weekend of sleepless nights and some flashy but mostly useless prototypes. Here, we stretched it out over four weeks, and we’re expecting real, meaningful outcomes,” says Siu, the hackathon director.

One week of training, three weeks of project development

In the first week, participants attended lectures with leading experts on key challenges Ukraine currently faces, from a talk on mine contamination with Andrew Heafitz PhD ’05 to a briefing on disinformation with Nina Lutz SM ’21, William Brannon SM ’20, and Yara Kyrychenko (Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab). Then, participants formed teams to develop projects addressing these challenges, with mentorship from top MIT specialists including Phil Tinn (AI & defense), Svetlana Boriskina (energy resilience), and Gene Keselman (defense innovation and dual-use technology).

“I really liked the solid structure they gave us — walking us through exactly what’s happening in Ukraine, and potential solutions,” says Timur Gray, a first-year in engineering at Olin College.

The five final projects spanned demining, drone technology, AI and disinformation, education for Ukraine, and energy resilience.

Supporting demining efforts

With current levels of technology, it is estimated that it will take 757 years to fully de-mine Ukraine. Students Timur Gray and Misha Donchenko, who is a sophomore mathematics major at MIT, came together to research the latest developments in demining technology and strategize how students could most effectively support innovations.

The team has made connections with the Ukrainian Association of Humanitarian Demining and the HALO Trust to explore opportunities for MIT students to directly support demining efforts in Ukraine. They also explored project ideas to work on tools for civilians to report on mine locations, and the team created a demo web page рішучість757, which includes an interactive database mapping mine locations.

“Being able to apply my skills to something that has a real-world impact — that’s been the best part of this hackathon,” says Donchenko.

Innovating drone production

Drone technology has been one of Ukraine’s most critical advantages on the battlefield — but government bureaucracy threatens to slow innovation, according to Oleh Deineka, who made this challenge the focus of his hackathon project.

Joining remotely from Ukraine, where he studies post-war recovery at the Kyiv School of Economics, Deineka brought invaluable firsthand insight from living and working on the ground, enriching the experience for all participants. Prior to the hackathon, he had already begun developing UxS.AGENCY, a secure digital platform to connect drone developers with independent funders, with the aim of ensuring that the speed of innovations in drone technology is not curbed.

He notes that Ukrainian arms manufacturers have the capacity to produce three times more weapons and military equipment than the Ukrainian government can afford to purchase. Promoting private sector development of drone production could help solve this. The platform Deineka is working on also aims to reduce the risk of corruption, allowing developers to work directly with funders, bypassing any bureaucratic interference.

Deineka is also working with MIT’s Keselman, who gave a talk during the hackathon on dual-use technology — the idea that military innovations should also have civilian applications. Deineka emphasized that developing such dual-use technology in Ukraine could help not only to win the war, but also to create sustainable civilian applications, ensuring that Ukraine’s 10,000 trained drone operators have jobs after it ends. He pointed to future applications such as drone-based urban infrastructure monitoring, precision agriculture, and even personal security — like a small drone following a child with asthma, allowing parents to monitor their well-being in real time.

“This hackathon has connected me with MIT’s top minds in innovation and security. Being invited to collaborate with Gene Keselman and others has been an incredible opportunity," says Deineka.

Disinformation dynamics on Wikipedia

Wikipedia has long been a battleground for Russian disinformation, from the profiling of artists like Kazimir Malevich to the framing of historical events. The hackathon’s disinformation team worked together on a machine learning-based tool to detect biased edits.

They found that Wikipedia’s moderation system is susceptible to reinforcing systemic bias, particularly when it comes to history. Their project laid the groundwork for a potential student-led initiative to track disinformation, propose corrections, and develop tools to improve fact-checking on Wikipedia.

Education for Ukraine’s future

Russia’s war against Ukraine is having a detrimental impact on education, with constant air raid sirens disrupting classes, and over 2,000 Ukrainian schools damaged or destroyed. The STEM education team focused on what they could do to support Ukrainian students. They developed a plan for adapting MIT’s Beaver Works Summer Institute in STEM for students still living in Ukraine, or potentially for Ukrainians currently displaced to neighboring countries.

“I didn’t realize how many schools had been destroyed and how deeply that could impact kids’ futures. You hear about the war, but the hackathon made it real in a way I hadn’t thought about before,” says Catherine Tang, a senior in electrical engineering and computer science.

Vlad Duda, founder of Nomad AI, also contributed to the education track of the hackathon with a focus on language accessibility and learning support. One of the prototypes he presented, MOVA, is a Chrome extension that uses AI to translate online resources into Ukrainian — an especially valuable tool for high school students in Ukraine, who often lack the English proficiency needed to engage with complex academic content. Duda also developed OpenBookLM, an AI-powered tool that helps students turn notes into audio and personalized study guides, similar in concept to Google’s NotebookLM but designed to be open-source and adaptable to different languages and educational contexts.

Energy resilience

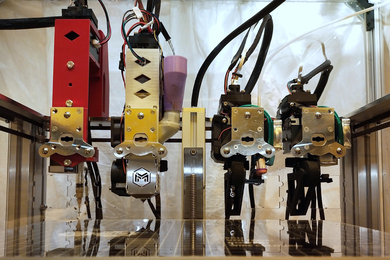

The energy resilience team worked on exploring cheaper, more reliable heating and cooling technologies so Ukrainian homes can be less dependent on traditional energy grids that are susceptible to Russian attacks.

The team tested polymer filaments that generate heat when stretched and cool when released, which could potentially offer low-cost, durable home heating solutions in Ukraine. Their work focused on finding the most effective braid structure to enhance durability and efficiency.

From hackathon to reality

Unlike most hackathons, where projects end when the event does, MIT-Ukraine’s goal is to ensure these ideas don’t stop here. All the projects developed during the hackathon will be considered as potential avenues for MIT’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) and MISTI Ukraine summer internship programs. Last year, 15 students worked on UROP and MISTI projects for Ukraine, contributing in areas such as STEM education and reconstruction in Ukraine. With the many ideas generated during the hackathon, MIT-Ukraine is committed to expanding opportunities for student-led projects and collaborations in the coming year.

"The MIT-Ukraine program is about learning by doing, and making an impact beyond MIT’s campus. This hackathon proved that students, researchers, and professionals can work together to develop solutions that matter — and Ukraine’s urgent challenges demand nothing less," says Elizabeth Wood, Ford International Professor of History at MIT and the faculty director of the MIT-Ukraine Program at the Center for International Studies.