The following announcement was released jointly by MIT Lincoln Laboratory and the National Strategic Research Institute.

MIT Lincoln Laboratory and the National Strategic Research Institute (NSRI) at the University of Nebraska (NU), a university-affiliated research center designated by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), have established a joint student research program.

The goal is to bring together the scientific expertise, cutting-edge capabilities, and student capacity of NU and MIT for critical issues within global health and agricultural security, aiming to foster solutions to detect and neutralize emerging biological threats.

"We are excited to combine forces with NSRI to develop critical biotechnologies that will enhance national security," says Catherine Cabrera, who leads Lincoln Laboratory's Biological and Chemical Technologies Group. "This partnership underscores our shared commitment to safeguarding America through scientific leadership."

"In an era of rapidly evolving dangers, we must stay ahead of the curve through continuous innovation," says David Roberts, the NSRI research director for special programs. "This partnership harnesses a unique combination of strengths from two leading academic institutions and two research institutes to create new paradigms in biological defense."

With funding from a DoD agency, the collaborators conducted a pilot of the program embedded within the MIT Engineering Systems Design and Development II course. The students’ challenge was to develop methods to rapidly screen for novel biosynthetic capabilities. Currently, such methods are limited by the lack of standardized, high-throughput devices that can support the culture of traditionally “uncultivable” microorganisms, which severely limits the cell diversity that could be probed for bioprospecting or biomanufacturing applications.

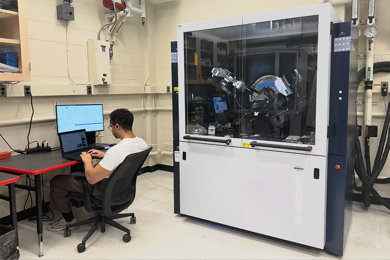

Led by Todd Thorsen, a technical staff member in the Biological and Chemical Technologies Group at Lincoln Laboratory, MIT students created the project, "Bioprospecting Experimentation Apparatus with Variable Environmental Regulation," which focused on developing simple high-throughput tools with integrated environmental control systems to expand the environmental testing envelope.

"This program, which emphasizes both engineering design and prototyping, challenges students to take what they learned in the classroom in their past undergraduate and graduate studies, and apply it to a real-world problem," Thorsen says. "For many students, the hands-on nature of this course is an exciting opportunity to test their abilities to prioritize what is important in developing products that are both functional and easy to use. What I found most impressive was the students’ ability to apply their collective knowledge to the design and prototyping of the biomedical devices, emphasizing their diverse backgrounds in areas like fluid mechanicals, controls, and solid mechanics."

In total, 12 mechanical engineering students contributed to the program, producing and validating a gas gradient manifold prototype and a droplet-dispensing manifold that has the potential to generate arbitrary pH gradients in industry-standard 96-well plates used for biomedical research. These devices will greatly simplify and accelerate the microculture of complex mixtures of organisms, like bacteria populations, where the growth conditions are unknown, allowing the end user to use the manifolds to dial in the optimal environmental parameters without the need for expensive, bulky hardware like the anaerobic chambers typically used for microbiology research.

"This class was my first experience with microfluidics and biotech, and thanks to our sponsors, I gained the confidence to pursue a career path in biotech," says Rachael Rosco, an MIT mechanical engineering graduate student. "The project itself was meaningful, and I know that our work will hopefully one day make an impact. Who knows, maybe one day it will lead to cultivating extremophile bacteria on a foreign planet!"

The collaboration will continue to seek DoD research funding to create workforce development opportunities for top scientific talent and introduce students to long-standing DoD challenges. Projects will take place nationwide at several NSRI, NU, Lincoln Laboratory, and MIT facilities.