One might argue that one of the primary duties of a physician is to constantly evaluate and re-evaluate the odds: What are the chances of a medical procedure’s success? Is the patient at risk of developing severe symptoms? When should the patient return for more testing? Amidst these critical deliberations, the rise of artificial intelligence promises to reduce risk in clinical settings and help physicians prioritize the care of high-risk patients.

Despite its potential, researchers from the MIT Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS), Equality AI, and Boston University are calling for more oversight of AI from regulatory bodies in a new commentary published in the New England Journal of Medicine AI's (NEJM AI) October issue after the U.S. Office for Civil Rights (OCR) in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued a new rule under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

In May, the OCR published a final rule in the ACA that prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, or sex in “patient care decision support tools,” a newly established term that encompasses both AI and non-automated tools used in medicine.

Developed in response to President Joe Biden’s Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence from 2023, the final rule builds upon the Biden-Harris administration’s commitment to advancing health equity by focusing on preventing discrimination.

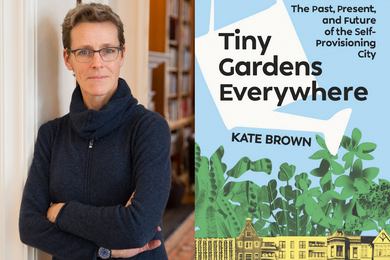

According to senior author and associate professor of EECS Marzyeh Ghassemi, “the rule is an important step forward.” Ghassemi, who is affiliated with the MIT Abdul Latif Jameel Clinic for Machine Learning in Health (Jameel Clinic), the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), and the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES), adds that the rule “should dictate equity-driven improvements to the non-AI algorithms and clinical decision-support tools already in use across clinical subspecialties.”

The number of U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved, AI-enabled devices has risen dramatically in the past decade since the approval of the first AI-enabled device in 1995 (PAPNET Testing System, a tool for cervical screening). As of October, the FDA has approved nearly 1,000 AI-enabled devices, many of which are designed to support clinical decision-making.

However, researchers point out that there is no regulatory body overseeing the clinical risk scores produced by clinical-decision support tools, despite the fact that the majority of U.S. physicians (65 percent) use these tools on a monthly basis to determine the next steps for patient care.

To address this shortcoming, the Jameel Clinic will host another regulatory conference in March 2025. Last year’s conference ignited a series of discussions and debates amongst faculty, regulators from around the world, and industry experts focused on the regulation of AI in health.

“Clinical risk scores are less opaque than ‘AI’ algorithms in that they typically involve only a handful of variables linked in a simple model,” comments Isaac Kohane, chair of the Department of Biomedical Informatics at Harvard Medical School and editor-in-chief of NEJM AI. “Nonetheless, even these scores are only as good as the datasets used to ‘train’ them and as the variables that experts have chosen to select or study in a particular cohort. If they affect clinical decision-making, they should be held to the same standards as their more recent and vastly more complex AI relatives.”

Moreover, while many decision-support tools do not use AI, researchers note that these tools are just as culpable in perpetuating biases in health care, and require oversight.

“Regulating clinical risk scores poses significant challenges due to the proliferation of clinical decision support tools embedded in electronic medical records and their widespread use in clinical practice,” says co-author Maia Hightower, CEO of Equality AI. “Such regulation remains necessary to ensure transparency and nondiscrimination.”

However, Hightower adds that under the incoming administration, the regulation of clinical risk scores may prove to be “particularly challenging, given its emphasis on deregulation and opposition to the Affordable Care Act and certain nondiscrimination policies.”