The grief of a parent who has lost a child is almost unimaginable, and words of sympathy are often and understandably inadequate. Yet, when Arthur Bahr learned a woman he knew had lost a son, he was able to reach out to her with a copy of “Pearl,” a 14th-century poem about a father who has lost his little girl and revisits her in a dream vision, where they discuss love and loss — and what is not lost.

“'Pearl' speaks to the universal human reality of grief and the desire to be with the person again,” Bahr says, noting that the woman later told him she had committed several lines of the poem to memory. “That is incredibly moving, that a poem can speak across centuries.”

Bahr, an associate professor of literature at MIT, is currently completing a book on the Pearl-Manuscript — a rare surviving 14th-century document that includes “Pearl” and three other works, “Patience,” “Cleanness,” and the famous chivalric romance story, “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” (recently adapted into a movie, "The Green Knight.") All four works are critical to our understanding of the medieval world and literature and two of them, “Pearl” and “Gawain,” are considered masterpieces.

“Part of my job,” Bahr says “is to help these texts be audible and resonant in a very different cultural, social, and religious context than the one in which they were created."

Speculation, in the original sense of the word

Bahr's book explores the tension between the unknown author’s spiritual angst and evolution, conveyed in the dream vision of the “Pearl” poem, and the very worldly commentary on 1300s court culture and the knight's chivalric code that appears in “Gawain.” “To have one manuscript/author conveying both the inner growth of 'Pearl' and something like 'Gawain,' which translates those soulful understandings and ideals to something more like the ‘real world,’ is an extraordinary achievement.”

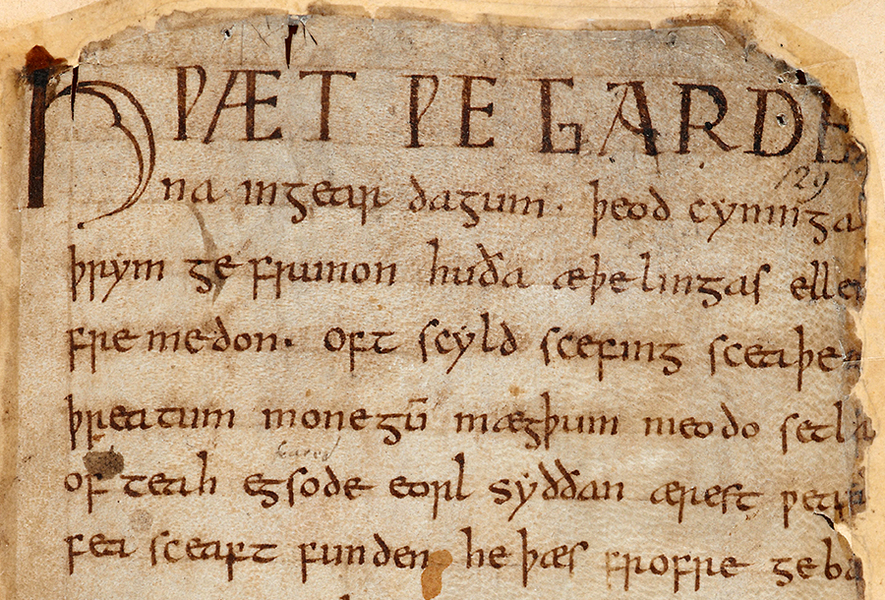

Handwritten on parchment, the Pearl-Manuscript is both a literary work and an artifact. There is only one copy in existence, and it is full of scribal errors — features common in medieval literature and part of the fascination of such works for Bahr. "These scribal errors show that there is a gap between what the author originally wrote and the words that have come down to us in material form. All we can do is speculate," he says, "in the original, medieval sense of the word: study what remains in order to trace the outlines of something not fully knowable.”Similarly, although it is generally believed (based on stylistic, thematic, and dialect similarities) that the four poems in the Pearl-Manuscript have the same author, that too is an educated speculation.

Like Ferraris on a racecourse

Bahr, who studied Latin and Ancient Greek in high school, fell in love with medieval literature as an undergraduate at Amherst College, where he majored in English, French, and medieval studies. He earned his PhD in English language and literature from the University of California at Berkeley, and initially envisioned settling into a teaching career at a small liberal arts college.

When he joined the MIT faculty in 2007, he had some trepidation about teaching at a research university; however, he quickly came to appreciate the Institute’s strengths. “It’s important to recognize how much of an outlier MIT is in requiring eight humanities, arts, and social science classes for all undergraduates, and requiring concentrations,” he says. “That gives people like me and others in the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences a platform that a lot of our colleagues elsewhere don’t have.”

MIT’s extraordinary students also won Bahr over. “MIT students are amazing,” he says, describing in particular how quickly they pick up Old English. “It’s like watching a Ferrari go around a racecourse. I just give them basic materials and they go to town. It’s inspiring.”

Yes, we have heard of the glory of the Spear-Danes' kings

A consummate teacher (in 2015, he received the Margaret MacVicar Faculty Fellowship, MIT’s highest undergraduate teaching award), Bahr typically teaches “Beowulf,” works of Chaucer, and other medieval texts. He also teaches more contemporary poetry and a class in the Old English language, which is among his favorites.

Old English, the language of Beowulf, dates to the mid-5th century and bears almost no resemblance to any version of English spoken today; its writing system even includes runic characters. Here’s the first line of Beowulf in Old English and in translation:

Hpæt pe gardena in geardagum beodcyninga brym gefrunon hu oa

aelingas ellen fremedon

Yes, we have heard of the glory of the Spear-Danes’ kings in the old days —

how the princes of that people did brave deeds.

Not surprisingly, Bahr teaches Old English because an MIT student asked him to.

It was 2013, and Bahr was teaching a class on Chaucer, who writes in Middle English, which is somewhat more accessible to our ears that its predecessor. Afterward, one student — Anna Ho ’14, then a junior and physics major — came up and asked if he would consider teaching Old English. “She's the reason I teach this class,” Bahr says. “I said yes, and also ‘you’re responsible for getting at least six students to sign up!’ On that first day, I had 26 students. And, the class has remained pretty popular ever since.”

Students are so engaged, he suggests, because medieval literature is both challenging and rewarding: it provides a portal to another world. Not only is the language almost foreign, but medieval texts commonly intertwine music, astronomy, grammar, religious doctrine, and fantasy in ways not often seen today. “The medieval worldview is so profoundly different from ours, and I think that’s exciting."

Performance

Bahr also says medieval literature “keeps you on your toes” — which is a particularly apt metaphor, since Bahr serves as a national judge with the United States Figure Skating Association. (He even judged Olympic gold medalist Nathan Chen when he was “a tiny little dynamo with a goofy bowl haircut.”)

Although Bahr himself gave up competitive skating in college, he often compares his academic career to the sport. For most of his skating career, while he had to be expert at carving compulsory figures into the ice (the origin of the term “figure skating”), he especially enjoyed practicing and performing free-skating routines. Similarly, as an academic he is committed to scholarly research, but passionately enjoys teaching. The connection between free skating and teaching? Both endeavors, Bahr explains involve “a kind of performance that aims to draw the audience in and make everyone in the room (or ice rink) feel like part of a shared experience.”

Making sure that the MIT classroom experience is a good one is important to Bahr, which is also why he recently dedicated two years to serving as chair of the Institute’s Committee on the Undergraduate Program (CUP), among the most significant at MIT. During his 2019-21 tenure, the CUP proposed new rules allowing all students broader access to pass/no-record grading and increasing spring credit limits for first-year students; MIT faculty ratified the proposals overwhelmingly. “These were the biggest changes in those areas in 20 and 30 years respectively,” Bahr says. “It was really rewarding.”

Middle English meets digital tech

Some changes can be difficult, of course. For Bahr, who loves old things, physical books, and presence, it was challenging to make the transition to remote, digital teaching during the pandemic. However, in the process he gained a greater appreciation for modern technology. “I began to use informal Zoom videos and audio recordings to try to model different ways of engaging with Middle English,” he says. “Somewhat to my surprise, these experiments were a success.”

Now Bahr has secured a grant to create a series of creative, online resources to support students studying Middle English; he plans to dive into that project as soon as he wraps up his book on the Pearl-Manuscript this spring. It is just one more way that Bahr is keeping medieval literature alive and well, and enthralling to 21st century readers at MIT and beyond.

Story prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Senior writer: Kathryn O'Neill

Editor and designer: Emily Hiestand