Parkinson’s disease is the fastest-growing neurological disease, now affecting more than 10 million people worldwide, yet clinicians still face huge challenges in tracking its severity and progression.

Clinicians typically evaluate patients by testing their motor skills and cognitive functions during clinic visits. These semisubjective measurements are often skewed by outside factors — perhaps a patient is tired after a long drive to the hospital. More than 40 percent of individuals with Parkinson’s are never treated by a neurologist or Parkinson’s specialist, often because they live too far from an urban center or have difficulty traveling.

In an effort to address these problems, researchers from MIT and elsewhere demonstrated an in-home device that can monitor a patient’s movement and gait speed, which can be used to evaluate Parkinson’s severity, the progression of the disease, and the patient’s response to medication.

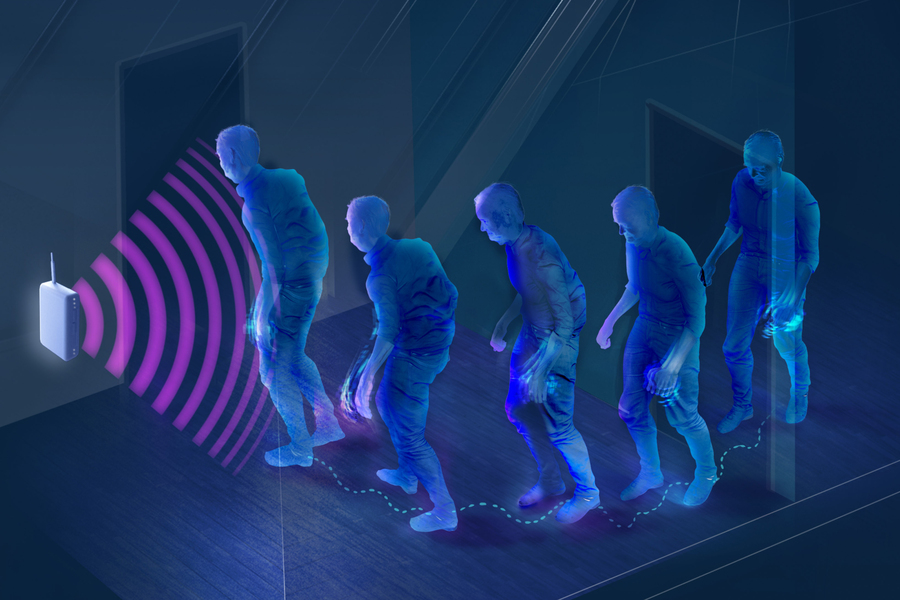

The device, which is about the size of a Wi-Fi router, gathers data passively using radio signals that reflect off the patient’s body as they move around their home. The patient does not need to wear a gadget or change their behavior. (A recent study, for example, showed that this type of device could be used to detect Parkinson’s from a person’s breathing patterns while sleeping.)

The researchers used these devices to conduct a one-year at-home study with 50 participants. They showed that, by using machine-learning algorithms to analyze the troves of data they passively gathered (more than 200,000 gait speed measurements), a clinician could track Parkinson’s progression and medication response more effectively than they would with periodic, in-clinic evaluations.

“By being able to have a device in the home that can monitor a patient and tell the doctor remotely about the progression of the disease, and the patient’s medication response so they can attend to the patient even if the patient can’t come to the clinic — now they have real, reliable information — that actually goes a long way toward improving equity and access,” says senior author Dina Katabi, the Thuan and Nicole Pham Professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS), and a principle investigator in the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and the MIT Jameel Clinic.

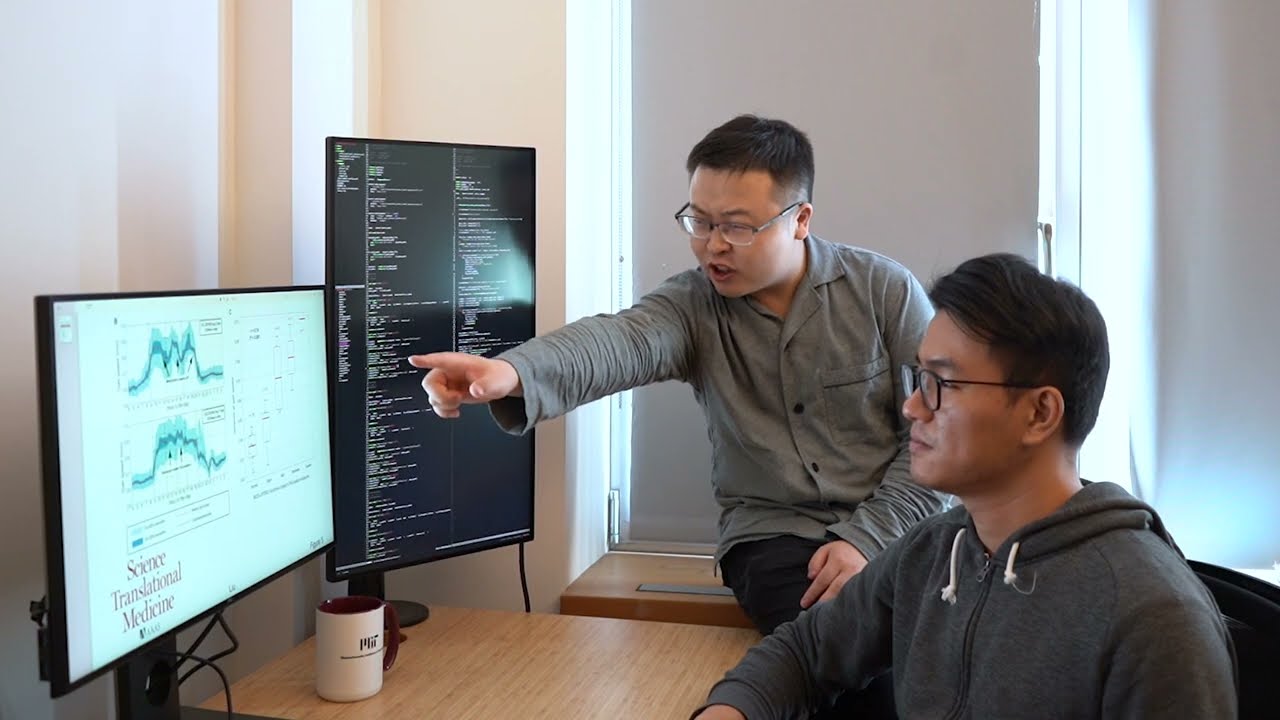

The co-lead authors are EECS graduate students Yingcheng Liu and Guo Zhang. The research is published today in Science Translational Medicine.

A human radar

This work utilizes a wireless device previously developed in the Katabi lab that analyzes radio signals that bounce off people’s bodies. It transmits signals that use a tiny fraction of the power of a Wi-Fi router — these super-low-power signals don’t interfere with other wireless devices in the home. While radio signals pass through walls and other solid objects, they are reflected off humans due to the water in our bodies.

This creates a “human radar” that can track the movement of a person in a room. Radio waves always travel at the same speed, so the length of time it takes the signals to reflect back to the device indicates how the person is moving.

The device incorporates a machine-learning classifier that can pick out the precise radio signals reflected off the patient even when there are other people moving around the room. Advanced algorithms use these movement data to compute gait speed — how fast the person is walking.

Because the device operates in the background and runs all day, every day, it can collect a massive amount of data. The researchers wanted to see if they could apply machine learning to these datasets to gain insights about the disease over time.

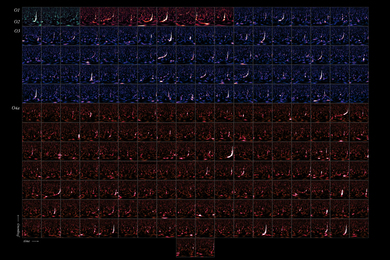

They gathered 50 participants, 34 of whom had Parkinson’s, and conducted a one-year study of in-home gait measurements Through the study, the researchers collected more than 200,000 individual measurements that they averaged to smooth out variability due to the conditions irrelevant to the disease. (For example, a patient may hurry up to answer an alarm or walk slower when talking on the phone.)

They used statistical methods to analyze the data and found that in-home gait speed can be used to effectively track Parkinson’s progression and severity. For instance, they showed that gait speed declined almost twice as fast for individuals with Parkinson’s, compared to those without.

“Monitoring the patient continuously as they move around the room enabled us to get really good measurements of their gait speed. And with so much data, we were able to perform aggregation that allowed us to see very small differences,” Zhang says.

Better, faster results

Drilling down on these variabilities offered some key insights. For instance, the researchers showed that daily fluctuations in a patient’s walking speed correspond with how they are responding to their medication — walking speed may improve after a dose and then begin to decline after a few hours, as the medication impact wears off.

“This enables us to objectively measure how your mobility responds to your medication. Previously, this was very cumbersome to do because this medication effect could only be measured by having the patient keep a journal,” Liu says.

A clinician could use these data to adjust medication dosage more effectively and accurately. This is especially important since drugs used to treat disease symptoms can cause serious side effects if the patient receives too much.

The researchers were able to demonstrate statistically significant results regarding Parkinson’s progression after studying 50 people for just one year. By contrast, an often-cited study by the Michael J. Fox Foundation involved more than 500 individuals and monitored them for more than five years, Katabi says.

“For a pharmaceutical company or a biotech company trying to develop medicines for this disease, this could greatly reduce the burden and cost and speed up the development of new therapies,” she adds.

Katabi credits much of the study’s success to the dedicated team of scientists and clinicians who worked together to tackle the many difficulties that arose along the way. For one, they began the study before the Covid-19 pandemic, so team members initially visited people’s homes to set up the devices. When that was no longer possible, they developed a user-friendly phone app to remotely help participants as they deployed the device at home.

Through the course of the study, they learned to automate processes and reduce effort, especially for the participants and clinical team.

This knowledge will prove useful as they look to deploy devices in at-home studies of other neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s, ALS, and Huntington’s. They also want to explore how these methods could be used, in conjunction with other work from the Katabi lab showing that Parkinson’s can be diagnosed by monitoring breathing, to collect a holistic set of markers that could diagnose the disease early and then be used to track and treat it.

“This radio-wave sensor can enable more care (and research) to migrate from hospitals to the home where it is most desired and needed,” says Ray Dorsey, a professor of neurology at the University of Rochester Medical Center, co-author of Ending Parkinson’s, and a co-author of this research paper. “Its potential is just beginning to be seen. We are moving toward a day where we can diagnose and predict disease at home. In the future, we may even be able to predict and ideally prevent events like falls and heart attacks.”

This work is supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health and the Michael J. Fox Foundation.