The subprime mortgage-bond meltdown. The dot-com boom. The Enron fiasco. The last couple of decades have seen their share of finance absurdities and scandals, but such episodes are hardly new. Indeed the most important of them all may be the South Sea Bubble, in which Britain’s South Sea Company floated shares based on the promise of future trade while assuming Britain’s national debt, but then collapsed in 1720, ruining many investors.

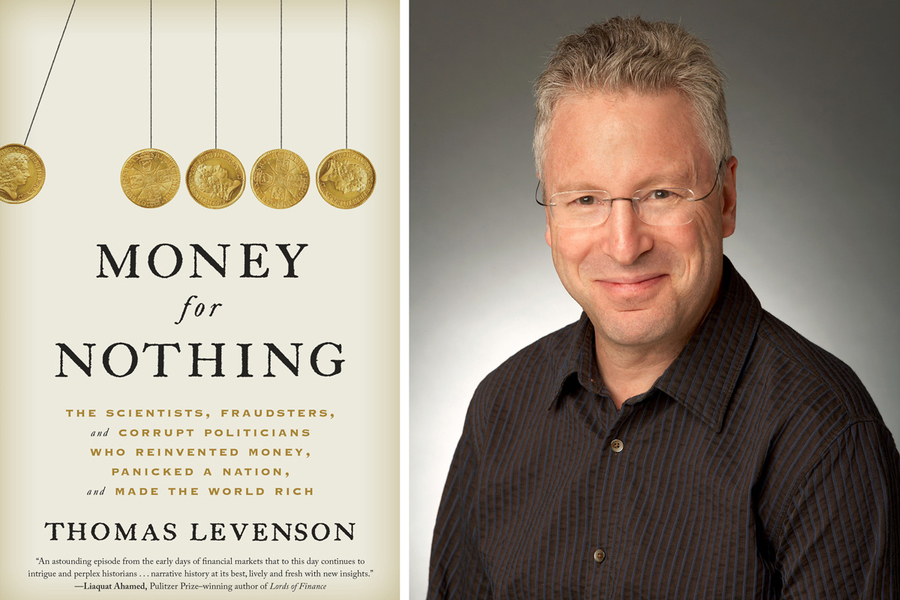

And yet, as MIT Professor Thomas Levenson explains in a new book — “Money for Nothing: The Scientists, Fraudsters, and Corrupt Politicians Who Reinvented Money, Panicked a Nation, and Made the World Rich,” just published by Crown — the South Sea Bubble helped shape modern finance and debt markets. MIT News talked to Levenson, a professor in MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing and the Comparative Media Studies / Writing program, about his new work.

Q: How did you become interested in the South Sea Bubble, and what is relevant about it today?

A: I was writing a book about Isaac Newton, [“Newton and the Counterfeiter,” 2009], and came upon a stray mention about how he lost money on the South Sea Bubble. I thought: This is really curious. Isaac Newton is the smartest man maybe ever, certainly the smartest of his time. What was he doing losing a lot of money? As I started looking at this quite famous case of stock market exuberance and crash, the more it became evident why it seemed like a good idea at the time to people.

What’s striking is how little has changed. A lot of things we think of as part of our 21st-century financial markets were already there in 1720. Do we still have the same dynamics and pathologies that created that disaster? Yes, absolutely. We’ve gotten cleverer, the math behind the financial markets is more complicated, but the basic architecture of financial crashes and bubbles is similar.

Q: One part of this book is an intellectual history: You look at Newton, the astronomer Edmond Halley, a scholar named William Petty, and other figures who, you contend, helped pave the way for these financial innovations. What’s the connection between their work and the South Sea Bubble?

A: In one way, the single most important takeaway from the book is that although the South Sea Bubble was a disaster for those who lost all their money, it worked. It was the final victory in a revolutionary change in the way Britain, uniquely among the nations, was able to fund its national obligations. It led to the creation of the first modern bond market. If you think of finance as a technology, that’s an incredibly powerful technology. Because it allows you to basically rent money from the future, use that money in the present to do things that help build the wealth of your nation going forward, and thus make the future richer than it otherwise would have been.

To get to that point, there needed to be a change in the way people understood the relationship of numbers to experience. The first part of the book shows how the scientific revolution and the financial revolution are intimately connected. They’re part of the same phenomenon, populated in part by the same people and driven by similar habits of thinking. The core idea is that empiricism and quantification allow you to apply disciplined reasoning, in the form of mathematics, to come up with insights that are available no other way.

Petty, a polymath who was a founder of the Royal Society, explicitly applied that doctrine of numbers, measure, and observation to practical problems [such as assessing the wealth of Ireland]. Edmond Halley applied calculations to provide the basis for life insurance. Yes, the scientific revolution involved things like what governs the motion of Jupiter, but it’s also: How should we think about probability and risk in human life? Isaac Newton wrote fairly well-thought-out memos on credit.

Q: All right, lightning round here. Who is the hero and who is the villain of the piece? What surprised you most about the South Sea Bubble? Who are your ideal readers?

A. There are no disinterested noble characters. The chief villain of the day is John Blunt, the secretary of the South Sea Company, the public face and one of the chief architects of the scheme. And it’s true he wanted to get rich and was unscrupulous in defense of the company. But I don’t think he set out to defraud the nation. He got on a horse that bolted and stayed on as long as he could. The great hero for me is clearly Robert Walpole, the parliamentary figure often seen as the first true prime minister in the British system of governance. In a sense he was lucky; if he’d been in power [when the scheme started], he might have been bribed. But he was a driven and devoted political leader who understood the problem well and worked his way toward a response. Like all his peers, he was perfectly happy with the ordinary corruption of the time. He got rich holding office. Just like Blunt wasn’t all bad, Walpole was not someone you’d entirely admire.

It surprised me that the sense of human passions around money felt so familiar. Newton was a formidable intellect who had the mathematical knowledge in his fingertips to reason his way to the flaw in the South Sea plan. Other people did that. Newton didn’t, because he was a human being and got caught up in the money mania. Even somebody with his focus and concentration and seeming detachment from human passions was still vulnerable to the same excitement.

My hope for this book is that it would build bridges between different groups: people who like history and want to understand how the past makes the present; people who want to understand how science works; and, I hope, a lot of people who want to understand ideas about finance and money. The book is in some ways an extended meditation on how money changes its character over time.