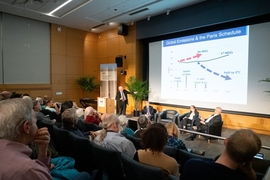

In the second of six symposia on climate change to be held this academic year, seven experts from around the country tackled the topic of “challenges of climate policy.” The Oct. 29 event included three panel discussions held at MIT’s Wong Auditorium.

Moderated by Richard Schmalensee, the Howard W. Johnson Professor of Management and professor of economics emeritus at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, the panelists discussed the social impacts caused by climate change; the kinds of adaptations that might help people cope with these impacts and limit their economic and physical harm; and possible solutions to the political, economic, and social factors affecting the world’s responses to this pressing issue.

Global climate change will have “huge impacts that will affect every sector” of society, and “its costs will be extremely high,” said Susanne Moser, a specialist in adaptation to climate change and director of Susanne Moser Research and Consulting. Although there are still uncertainties about the rate and extent of climate change, she said, “uncertainty is a reason to act, not to wait.”

Compared to the responses that experts say are required to forestall the worst effects of climate change, efforts around the world still fall far short, Moser said: “Most responses are just reactive. There’s no unifying vision, there’s no agreement on social equity priorities, and there is a surprising lack of urgency,” she said.

Even most universities, she noted, do not yet have clear and easy ways to find information on their efforts toward adaptation to climate change, or programs for students to specialize in that field. “You can barely find it on their websites,” she said.

Some people fear that an emphasis on adaptation could make people complacent because they see less need to to reduce greenhouse gases if plans are underway to adapt to a changed climate. But Moser disputed that claim. “We’ve studied that” and found the reverse to be true, she said. When people see just how difficult and expensive the processes of adaptation are, compared to measures to reduce emissions, “they realize reduction [of emissions] is a bargain,” and their motivation to deal with that issue actually increases.

Andrew Steer, president and CEO of the World Resources Institute, urged listeners: “Let’s get serious about climate change adaptation, as if our lives depended on it. Which it may.” He said people need to start looking seriously at ways to respond to five different key areas of global change: higher temperatures, rising seas, stronger storms, shifting rainfall patterns, and acidification of the oceans.

The impacts are likely to be extreme, he said. Just adapting to the changes directly affecting coastal cities could cost upward of a trillion dollars a year, he said. And yet, when governments and agencies allocate resources to dealing with climate change, so far only about 10 percent of that money goes toward adaptation, versus 90 percent toward mitigation, or efforts to slow or reverse the release of climate altering emissions. Both are crucial, he said, but adaptation should not be ignored since even with aggressive mitigation policies, a significant amount of climate change is already unavoidable.

“Adaptation is a moral imperative,” he said, and also “an ecological imperative, and a massive economic imperative.”

Adaptation need not be as expensive as people think, Steer added. Many of the measures that are needed to adapt to a warming world also have other benefits, he pointed out. As an example, drip irrigation was invented as a way to deal with drought conditions, but it is also an inherently more efficient system, greatly reducing the amount of water needed for crops and the need for power to operate pumps. That greater efficiency for farmers can lower their costs, and thus make food less expensive. “Done right, adaptation can have all kinds of dynamic benefits,” he said.

Much more research is needed to quantify the expected effects of a warming planet, said Max Auffhammer, a professor of international sustainable development at the University of California at Berkeley. To study and quantify the economic harm done by 1 ton of carbon dioxide (roughly the amount emitted by driving a car from Cambridge to Berkeley, he said) is a very difficult task. The best existing estimates were made back in the 1990s, and much has been learned since then. Models need to encompass global coverage, establish causal connections, and anticipate significant technological changes. Imagine, he said, trying to predict in the late 1800s the energy that would be used for cooling houses today.

Whereas some might say “we got this” in terms of the scientific answers about the effects of climate change, he said, “We don’t got this. There’s a lot of work to be done.”

Kathleen Hicks, director of the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said that the U.S. military forces, unlike many politicians, understand the problem of climate change and take it seriously. Partly that’s because it’s in their nature to always be assessing potential risks and planning how to respond to them, and they are highly trained in how to do so. In addition, they are already feeling the effects directly, with even inland bases such as one in Nebraska affected by severe flooding, likely exacerbated by climate change.

“Climate is a national security concern that is not debated in the security community,” she said.

But public opinion has also come a long way over the last several years, said Steven Ansolabehere, a professor of government at Harvard University. “The American public accepts that climate change is coming and is a concern,” he said, but “a majority also feel it’s distant,” with consequences beyond their lifetimes, whereas scientists studying the problem say its damaging effects are already being seen clearly in many parts of the world today. This discrepancy “is the heart of the problem, and it has implications for any policy we take,” he said.

But Ansolabehere said that there are already interesting differences in the responses of younger people compared to their elders. The difference in the degree of urgency seen in the issue of climate change between younger (“millennial”) Republicans and “boomer” generation Republicans is just as big as the difference between Democrats and Republicans overall, he said. And, he said, linking policies to tackle climate change to other benefits such as clear air and clean water — for example through the closing of coal-fired power plants — is a more effective strategy for gaining support than just emphasizing the climate benefits.

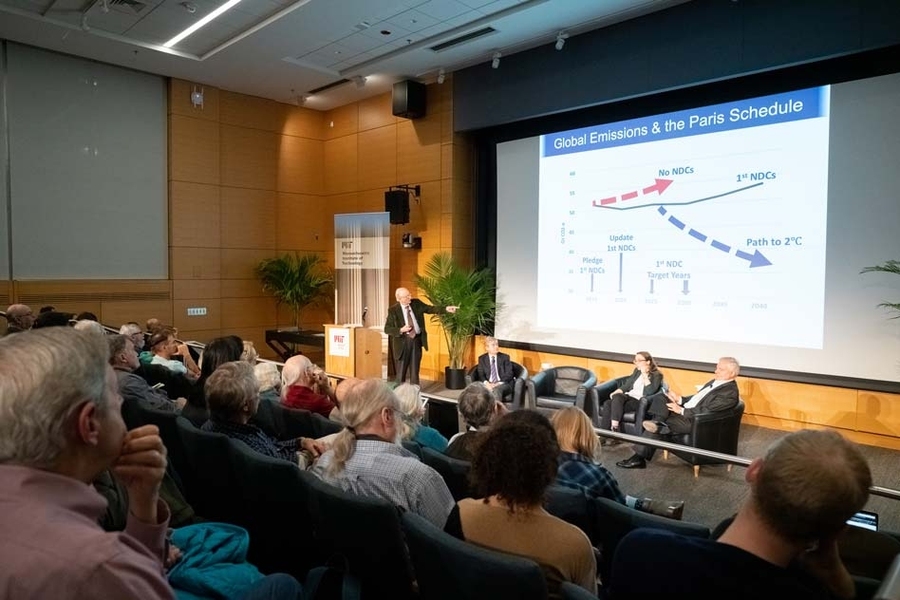

Henry Jacoby, the William F. Pounds Professor of Management Emeritus at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, said that the issue of climate change reflects the well-known “commons problem,” where a few bad actors can undermine a large group’s mutual dependence on common resources. He compared it to a shared refrigerator in a dorm, where there is little control over someone making off with someone else’s stored drink. Similarly, nations will almost always end up acting in their own self interest rather than for a more abstract common good.

The way nations deal with that is through international agreements and treaties, such as the Paris Agreement on climate change. But that agreement is entirely voluntary, consisting of individual national pledges without any mechanism for enforcement. Just as with the dorm fridge, there’s no police officer to call about an infraction.

By 2030, projections show that about three-quarters of all greenhouse emissions will be coming from developing countries — the places that can least afford to spend money to address the problem. “There’s going to have to be some financial transfer” from the wealthier countries to help those developing countries reduce their emissions, Jacoby said.

Leah Stokes PhD ’15, an assistant professor of political science at the University of California at Santa Barbara, said that the three decades of climate denial efforts by major fossil fuel companies “has been extremely influential,” and will require significant efforts to reverse. But she also noted several reasons to expect that these attitudes are changing.

For one, the raging wildfires in California and other places provide a vivid reminder that a significant increase in such fires is one of the expected effects of a warmer planet with more frequent and deeper droughts. In addition, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s most recent report set a target of 2030 by which the world must significantly reduce emissions. That short timeline means that “it’s suddenly not about the distant future,” but a time when most people still expect to be alive, she said, making the problem seem much more urgent. And increasing public actions, such as the recent Climate Strike initiated by Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg, have also raised the public awareness of the issue’s seriousness.

Stokes pointed to significant areas of progress, such as the rapid growth of solar and wind power and electric vehicles, and state and local regulations that have continued to push for progress even as federal regulations have been cut back. But to continue this progress will require much more. “We must have solutions at the scale of the crisis,” she said. One approach that could help is to emphasize the potential for new, well-paying jobs in the renewable energy field. “It can’t just be about sticks,” she said, adding that there needs to be tangible carrots as well.