About 2 billion people around the world suffer from deficiencies of key micronutrients such as iron and vitamin A. Two million children die from these deficiencies every year, and people who don’t get enough of these nutrients can develop blindness, anemia, and cognitive impairments.

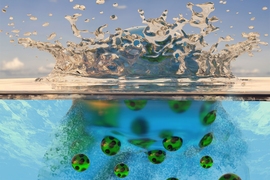

MIT researchers have now developed a new way to fortify staple foods with these micronutrients by encapsulating them in a biocompatible polymer that prevents the nutrients from being degraded during storage or cooking. In a small clinical trial, they showed that women who ate bread fortified with encapsulated iron were able to absorb iron from the food.

“We are really excited that our team has been able to develop this unique nutrient-delivery system that has the potential to help billions of people in the developing world, and taken it all the way from inception to human clinical trials,” says Robert Langer, the David H. Koch Institute Professor at MIT and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research.

The researchers now hope to run clinical trials in developing nations where micronutrient deficiencies are common.

Langer and Ana Jaklenec, a research scientist at the Koch Institute, are the senior authors of the study, which appears today in Science Translational Medicine. The paper’s lead authors are former MIT postdocs Aaron Anselmo and Xian Xu, and ETH Zurich graduate student Simone Buerkli.

Protecting nutrients

Lack of vitamin A is the world’s leading cause of preventable blindness, and it can also impair immunity, making children more susceptible to diseases such as measles. Iron deficiency can lead to anemia and also impairs cognitive development in children, contributing to a “cycle of poverty,” Jaklenec says.

“These children don’t do well in school because of their poor health, and when they grow up, they may have difficulties finding a job, so their kids are also living in poverty and often without access to education,” she says.

The MIT team, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, set out to develop new technology that could help with efforts to fortify foods with essential micronutrients. Fortification has proven successful in the past with iodized salt, for example, and offers a way to incorporate nutrients in a way that doesn’t require people to change their eating habits.

“What’s been shown to be effective for food fortification is staple foods, something that’s in the household and people use every day,” Jaklenec says. “Everyone eats salt or flour, so you don’t need to change anything in their everyday practices.”

However, simply adding vitamin A or iron to foods doesn’t work well. Vitamin A is very sensitive to heat and can be degraded during cooking, and iron can bind to other molecules in food, giving the food a metallic taste. To overcome that, the MIT team set out to find a way to encapsulate micronutrients in a material that would protect them from being broken down or interacting with other molecules, and then release them after being consumed.

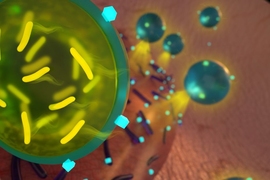

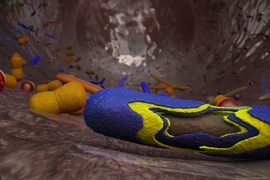

The researchers tested about 50 different polymers and settled on one known as BMC. This polymer is currently used in dietary supplements, and in the United States it is classified as “generally regarded as safe.”

Using this polymer, the researchers showed that they could encapsulate 11 different micronutrients, including zinc, vitamin B2, niacin, biotin, and vitamin C, as well as iron and vitamin A. They also demonstrated that they could encapsulate combinations of up to four of the micronutrients together.

Tests in the lab showed that the encapsulated micronutrients were unharmed after being boiled for two hours. The encapsulation also protected nutrients from ultraviolet light and from oxidizing chemicals, such as polyphenols, found in fruits and vegetables. When the particles were exposed to very acidic conditions (pH 1.5, typical of the pH in the stomach), the polymer become soluble and the micronutrients were released.

In tests in mice, the researchers showed that particles broke down in the stomach, as expected, and the cargo traveled to the small intestine, where it can be absorbed.

Iron boost

After the successful animal tests, the researchers decided to test the encapsulated micronutrients in human subjects. The trial was led by Michael Zimmerman, a professor of health sciences and technology at ETH Zurich who studies nutrition and food fortification.

In their first trial, the researchers incorporated encapsulated iron sulfate into maize porridge, a corn-derived product common in developing world, and mixed the maize with a vegetable sauce. In that initial study, they found that people who ate the fortified maize — female university students in Switzerland, most of whom were anemic — did not absorb as much iron as the researchers hoped they would. The amount of iron absorbed was a little less than half of what was absorbed by subjects who consumed iron sulfate that was not encapsulated.

After that, the researchers decided to reformulate the particles and found that if they boosted the percentage of iron sulfate in the particles from 3 percent to about 18 percent, they could achieve iron absorption rates very similar to the percentage for unencapsulated iron sulfate. In that second trial, also conducted at ETH, they mixed the encapsulated iron into flour and then used it to bake bread.

“Reformulation of the microparticles was possible because our platform was tunable and amenable to large-scale manufacturing approaches,” Anselmo says. “This allowed us to improve our formulation based on the feedback from the first trial.”

The next step, Jaklenec says, is to try a similar study in a country where many people experience micronutrient deficiencies. The researchers are now working on gaining regulatory approval from the Joint Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization Expert Committee on Food Additives. They are also working on identifying other foods that would be useful to fortify, and on scaling up their manufacturing process so they can produce large quantities of the powdered micronutrients.

Other authors of the paper are Yingying Zeng, Wen Tang, Kevin McHugh, Adam Behrens, Evan Rosenberg, Aranda Duan, James Sugarman, Jia Zhuang, Joe Collins, Xueguang Lu, Tyler Graf, Stephany Tzeng, Sviatlana Rose, Sarah Acolatse, Thanh Nguyen, Xiao Le, Ana Sofia Guerra, Lisa Freed, Shelley Weinstock, Christopher Sears, Boris Nikolic, Lowell Wood, Philip Welkhoff, James Oxley, and Diego Moretti.