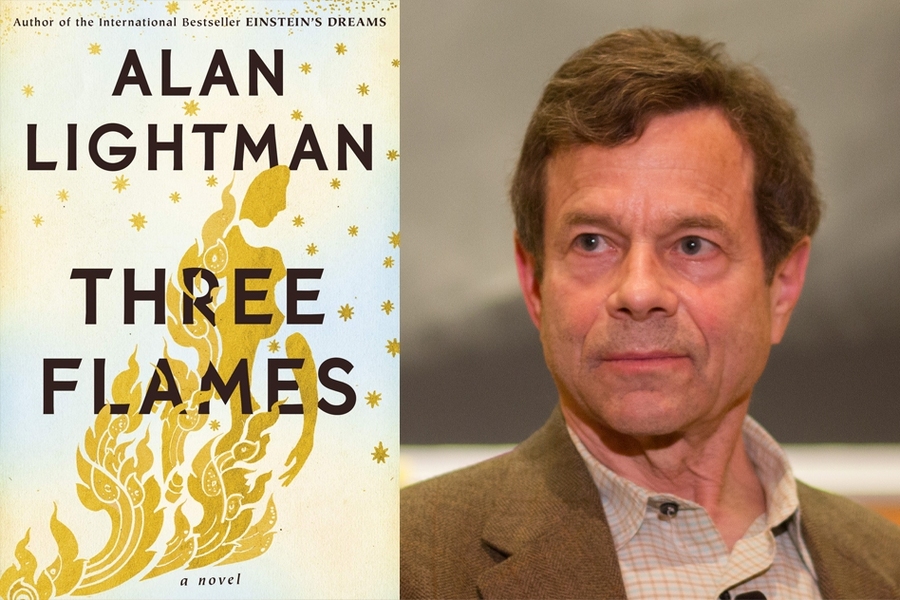

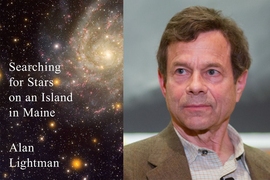

MIT’s Alan Lightman is a physicist who made a leap to becoming a writer — one with an unusually broad range of interests. In his novels, nonfiction books, and essays, Lightman, a professor of the practice of the humanities at MIT, has explored many topics, from science to society. His new novel, “Three Flames,” recently published by Counterpoint Press, follows the fortunes of a family in post-civil war Cambodia. It’s a topic Lightman knows well: He is the founder the Harpswell Foundation, which works to empower a new generation of female leaders in Cambodia and across Southeast Asia. Lightman recently talked to MIT News about “Three Flames.”

Q: What are the origins of ‘Three Flames”?

A: I’ve been working in Cambodia for 15 years, and I’ve spent a lot of time there, and I’ve heard a lot of stories of families, particularly [about] the residue of the Khmer Rouge genocide in the mid-1970s. Just about anybody you meet in Cambodia today has a relative who was killed or starved or tortured over that period of time. So it’s affected everybody in the entire country. And I have been very interested in how a country can recover its humanity after that kind of devastation, when family members were turned against each other. The Khmer Rouge soldiers rounded up anybody that they had the slightest suspicion about, and encouraged families to turn in anybody that they had any suspicion about. It disrupted families and led to an every-person-for-themselves mentality, which still hasn’t disappeared.

In the face of all that destruction and moral degradation, I also heard stories of courage and resilience and forgiveness. After many years, I thought I was beginning to understand the culture enough to begin writing stories about it. But I waited 10 years before I started writing anything. You have to understand a culture much more deeply to write fiction about it than to write nonfiction, because fiction involves small daily mannerisms, which you have to get right. And you don’t pick that up from a couple of trips.

Q: There are many connected stories in this novel, and many distinctive characters. What is the main theme, and how did you weave that in throughout different parts of the book?

A: The overriding story is the struggle that women have in a male-dominated society. And that, of course, is true not only in Cambodia but in many countries, even the U.S. Almost every chapter of the book has that struggle in it. … A number of the [other] themes in the book are universal. I hope the themes of redemption, and forgiveness, and revenge, and women’s struggles will go beyond Cambodia.

Five years ago, I wrote the first chapter of the book, about the mother, Ryna. When I wrote that, it was a stand-alone short story [published in the journal Daily Lit, and as an Amazon Kindle single]. In that story, I mention other members of the family. One daughter is married off to a rubber merchant; another one went to Phnom Penh to work to pay off a family debt; the son is kind of a ne’er-do-well; the father is very ignorant, sexist, and condescending. About a year after writing the first story, I began wondering about the other family members. Once you write a character in fiction, they come to life and stay in your head. And so I decided I would write a story about each member of the family. Of course, I had to interweave all the stories, as they involve the same family.

Q: How did you then assemble those elements into a cohesive story? It must have been fairly complicated to place these parts of the story into a larger narrative.

A: After I had written the book, I decided to place the stories in the order where they would have the most dramatic impact. For the story about Pich, the father, I wanted to wait until that character had been developed to show how he became the person he is, because none of us are all good or bad. The story about Nita [a daughter of Pich], I wanted to save until the later part of the book because it’s such a shocking story. The story about Srepov has to come last, because she’s the only hope for the future. The date of each story is when the most dramatic action happened to each character, the most influential [moment] in shaping who they are.

[In books], there are two times that are important. There’s chronological time, and then the time of readerly experience. Taking the Pich story as an example, in my view as a writer it’s more powerful to first see Pich as he is today, an unsympathetic, dictatorial, cruel father, and to even grow to hate him. Then, only later in the book, we see him in childhood and see the forces that shaped him as he is. To save the childhood portrait for later, that’s a more powerful experience for the reader.