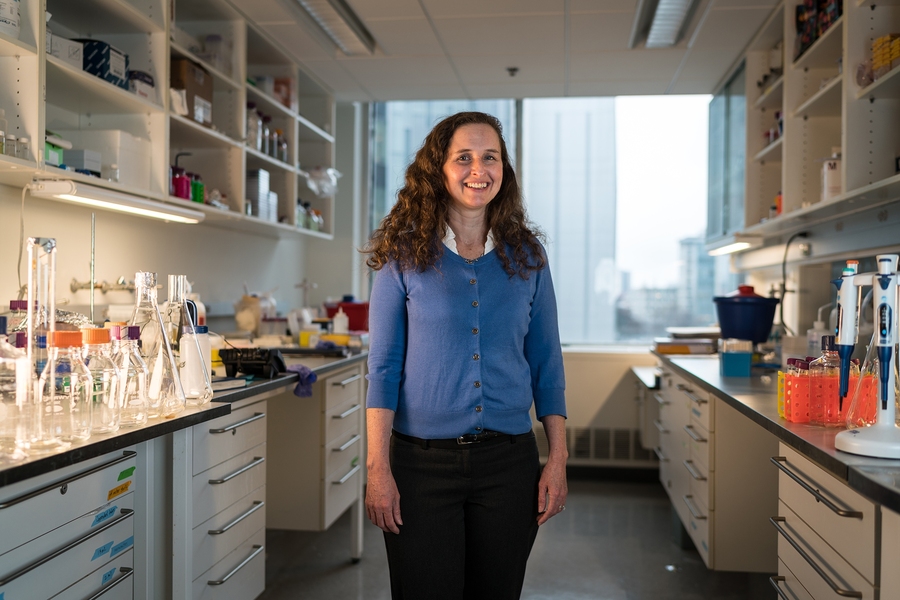

“In my lab, we bridge a gap,” says Hadley Sikes. “We try to figure out how to take established science and implement it in clinical practice in a reliable, easy and cost-effective way.”

The associate professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering is one of an increasing number of MIT faculty members who do what might best be called public engineering, which emphasizes the interaction between society and technology.

Her team is integrating molecular technologies for diagnosing malaria and other infectious diseases in resource-limited areas, including Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia. At the same time, her lab is developing technologies to predict the effectiveness of particular chemotherapeutics in treating an individual patient’s cancer that might one day be used at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The desire to bridge that gap — between theory and practice, the local and the global, the developed world and the developing world — inspired Sikes to transition from academic basic science to chemical engineering when she was a post-doc. That decision has guided her career and teaching ever since.

Graduate students in the Sikes Lab, for example, study research literature on molecular signatures of health and disease, which, in turn, informs their ongoing design of technologies to help medical practitioners save lives in rural villages, in urban centers, and in countries rich and poor.

“I want our devices to be widely used in clinical settings all over the world,” says Sikes. “Their widespread adoption would have a profound impact on people suffering from various diseases. I want to be part of that — and I want our lab to be part of that.”

Learning by doing

Growing up in Alabama, Sikes developed a love of science, math, and innovation, but her public school lacked the funds for high-tech equipment. The school did, however, host an annual science fair, which inspired Sikes to be creative in the way she embraced project design and drew on her accumulated knowledge.

Sikes passes on such lessons to her students in courses like 10.492 (Integrated Chemical Engineering), a senior design class focused on biosensors. The class acquaints students with approaches to the detection and quantification of biological molecules for purposes ranging from medical diagnostics to environmental monitoring to food safety to defense.

In a group design project, students creatively apply concepts from kinetics, thermodynamics, and transport to current problems.

“I give students an opportunity to practice what they’ve learned in their core classes,” she says. “They tap that knowledge in new ways and apply it in practice.”

The here and now

Google software engineer Derek Wu ’15, a former 10.492 student, says his design project involved drawing on concepts from other disciplines, and applying that knowledge in the context of biology and human health.

His group proposed using microneedle patches, rather than injections, to deliver synthetic biomarkers into the human body to detect non-communicable diseases, such as cancer or thrombosis. Using the patches requires much less training compared with injections — a useful technique, particularly in resource-limited settings.

“Whenever I had questions, Hadley always approached answers from the student point of view,” recalls Wu. “I always felt she was on my side when she was helping me address various challenges.”

His former classmate Matias Porras ’15, now a program analyst at Genentech in San Francisco, worked on the project with Wu. “I really enjoyed finding a way to improve the way diagnostics are done in developing countries,” he says.

Sikes says MIT is at the center of innovation — and that’s exactly where she, and her students love to be.

“Students can start to do the clinical testing and prototyping right away," she says. “Things seem possible here. Things that seem kind of far-off maybe in other places — those things are happening here.”